The surprise announcement that the United States, United Kingdom and Australia have agreed a defense pact that will go some way toward countering China in the Indo-Pacific region sparked an array of emotions. In Europe, it left the French government furious and European Union officials somewhat confused as to what the bloc should do about China.

The deal, which was unveiled on Wednesday, will see the US and UK send strategic and technical teams to Australia to help the country procure nuclear-powered submarines. It also meant that the Australian government cancelled a multi-billion contract for non-nuclear submarines with a French manufacturer.

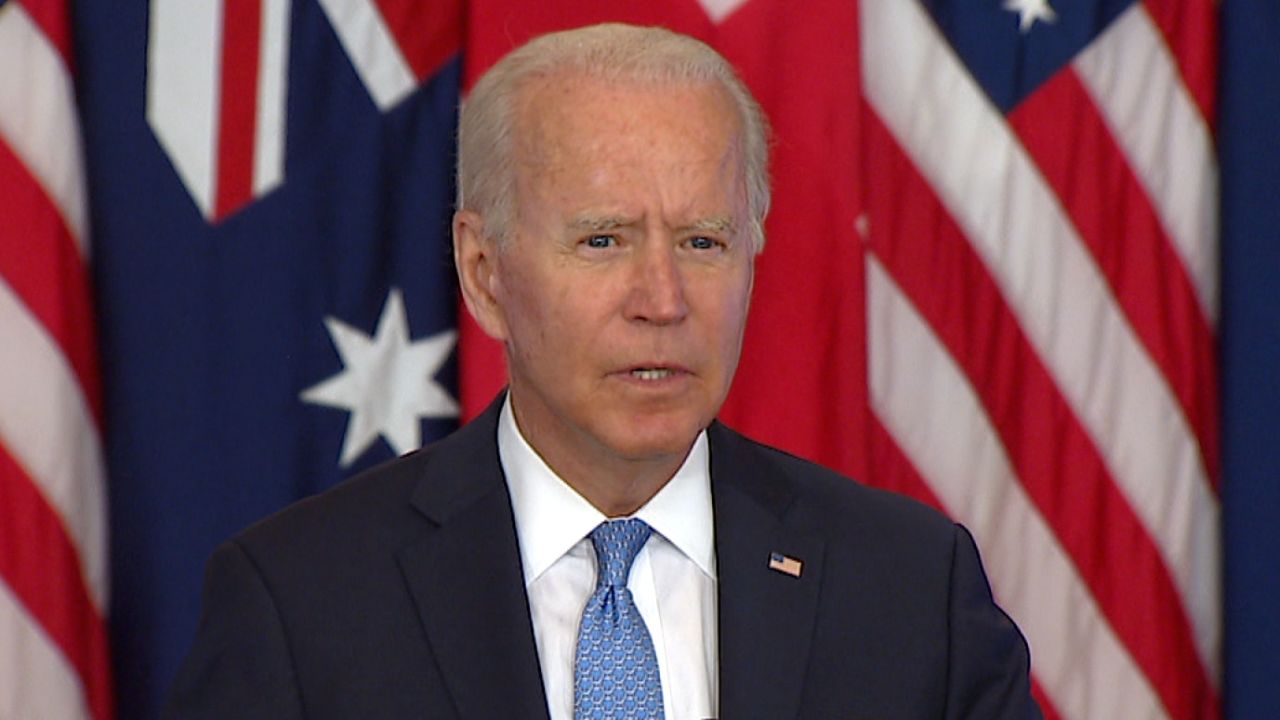

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian described this as a “real stab in the back” from Australia. He also fired a shot at US President Joe Biden, saying that the sudden announcement of this deal without consulting other allies was a “brutal and unilateral decision” that “resembles a lot of what Mr. Trump was doing.”

Leaving aside France’s wounded pride, the new geopolitical pact between English-speaking maritime powers (known as AUKUS and pronounced “aw-kiss”) presents a strategic headscratcher for the EU.

Officials in Brussels told CNN that the timing of the AUKUS announcement was viewed dimly, as the EU’s high representative on foreign affairs was set to deliver his own strategy for the Indo-Pacific on Thursday afternoon.

At best, it was considered a bit rude; at worst, it confirmed that, despite Brussels’ global ambitions, it is not taken seriously as a geopolitical player.

Either way, Brussels is feeling scarred. A senior EU official told CNN that this was “English-speaking countries” who are “very belligerent” forming an alliance “against China.” The official noted that these were the same nations who took the lead in invading Afghanistan and Iraq. “And we all know the results,” they added.

The EU’s strategy for handling China differs from the US in one major way: the EU actively seeks cooperation with China, and sees it as an economic and strategic partner.

Brussels officials believe that by trading and working with China, not only can they lean on Beijing to reform their human rights and energy policies, but also use a good relationship with China to act as a buffer between Beijing and Washington, thus giving the EU a clear and important geopolitical role.

The AUKUS deal has, in the eyes of some, undermined any real claim that Brussels had as an influential presence on the world stage.

“The fact that the US is willing to spend more political capital and invest in security and defense ties with the UK and Australia before reaching out to EU powers is quite revealing,” said Velina Tchakarova, director of the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy.

She added that despite many positive developments in understanding the importance of this region, “it is obvious that the EU must first become a security actor in the Indo-Pacific in order to be taken seriously by the partners in the Anglosphere.”

So how can the EU do this?

This is the million-dollar question and the source of a lot of disagreement between member states. There is no consensus on what European defense means or should look like. France, the only major military power in the bloc, has been pushing for a coordinated defense policy that provides the bloc with real capabilities.

One EU official familiar with the matter told CNN that the recent developments in Afghanistan and the AUKUS announcement has only solidified France’s view that the EU needs the capacity to defend its interests and build a presence in the Indo-Pacific region.

However, France really is an outlier on this matter.

“When I see [French President Emmanuel] Macron and his team talk about standing troops, I just can’t see it ever happening,” said one EU diplomat. “National leaders have to send troops into battle. It won’t be the EU blamed when people come back in body bags.”

Other diplomats and officials see potential for member states working together on more efficient procurement, meaning each country buys specific things that play to their military strengths. However, they still draw the line at the idea of deploying troops.

“Neutral countries like Austria, Ireland, Finland and Sweden will never be comfortable with deploying troops to conflict zones,” said one diplomat. “What we could work with EU partners on, however, are things like training troops in third countries and peacekeeping on borders.”

Beneficial as this would be for Europe, it’s a far cry from asserting serious military heft in a world where that seems to matter enormously.

Steven Blockmans, director of research at the Centre for European Policy studies, explained that as Europe’s defensestrategy develops, it will probably lean further toward these smaller acts of cooperation than the French ideal.

“The other big member state, Germany, has always been very clear that any such integration policy, especially in the field of defense and security, needs to be as inclusive as possible and bring as many of the 27 member states along with it,” Blockmans said.

“The AUKUS announcement therefore forces France to rethink its defense relationship with the Anglosphere and work harder with fellow member states to raise the level of ambition in European defense cooperation,” he added.

That rethink could be instructive for those wondering where Europe’s foreign policy goes next.

Tchakarova said that hard decisions will need to be made by the major European powers on how much they want to isolate themselves from “their most significant transatlantic partner in their approach to the region and to China in particular.”

She added that as the US-China battle for soft power escalates, Brussels’ plan of “oscillating between Washington and Beijing will not work for the EU in the long run,” if countries like France and Germany decide they want a closer relationship with their Anglosphere allies.

The EU has spent years devising a complicated plan to sit somewhere between the US and China, and in doing so hold huge amounts of soft power. Instead, the AUKUS plan, which rests on traditional hard power, was agreed with Brussels left in the dark and France hung out to dry.

No matter how much EU officials try to spin this as being somehow separate from its lofty ambitions for the next few years, Biden’s decision to work with his traditional allies using traditional hard power on the biggest issue facing the democratic world gives a clear story of where serious geopolitical power will lie over the next few years.

While the EU holds huge economic power, the events of the past 24 hours have been a nasty reminder that, in certain areas, Brussels still has a long way to go if it wants to sit between China and the US without getting squashed.