The closely watched California gubernatorial recall election on Tuesday is poised to send precisely the opposite political message that its proponents initially intended.

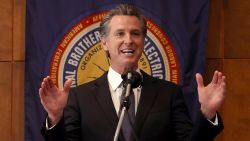

It was a strong gust of discontent in the state’s most conservative regions last year over Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom’s stringent measures to fight the Covid-19 pandemic that allowed the recall to qualify for the ballot at all. But now a swell of support in the broader statewide electorate for the more recent steps Newsom has taken to combat the Delta variant outbreak – particularly the vaccine mandates he’s imposed for educators, health care workers and state employees – has positioned him for a potentially resounding victory, according to the latest polls.

Recall proponents had hoped to demonstrate the political potency of the backlash against tough Covid regulations and discourage other states from implementing them; instead, the race now seems more likely to embolden Democrats in California and beyond by documenting the existence of a new “silent majority” of vaccinated Americans ready for tougher measures against the minority of adults who have resisted the shot.

“What we were able to do is take the governor’s clear national leadership on vaccine mandates and drive it as the core contrast in the election,” says Sean Clegg, a strategist for the Newsom campaign. “I hope what we’ve shown Democrats … is to embrace [mandates] as a partisan question, put up our dukes and get Republicans on the wrong side of the fence on this thing.”

Solidly blue California may be uniquely favorable terrain for Democrats to contest this argument. But Newsom’s success in gaining the upper hand over the recall by leaning into his support for vaccine mandates may be seen in retrospect as a turning point in the Democratic approach to the pandemic.

Already, Gov. Phil Murphy and Terry McAuliffe, the Democratic candidates in this November’s New Jersey and Virginia gubernatorial races, have also emphatically embraced mandates – and sharpened their contrast on the issue with their GOP opponents, who are rejecting them. Most dramatically, President Joe Biden last week pivoted from a strategy of relying primarily on inducements and persuasion to increase vaccination rates to a more confrontational approach centered on proposals to require health care workers and employees at larger firms to obtain the vaccine or undergo weekly testing.

Almost uniformly, Republicans have condemned these mandate proposals, with a succession of GOP governors promising to sue Biden once he finalizes his plan. But rather than shrinking from this fight, more Democrats appear to welcome it, believing that Republicans are isolating themselves by agitating so unreservedly for the “rights” and “choices” of the one-quarter of adults who remain unvaccinated when the three-fourths of adults who have received at least one dose are increasingly exasperated with them, polls show. A substantial win for Newsom on Tuesday would likely solidify the resolve among many Democrats that mask and vaccine mandates represent a sound strategy not only for public health but also the next elections.

“Around the issue of mandates there is a lot of support because people want this thing to be over,” says Mark Baldassare, president and CEO of the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California, which conducts regular statewide surveys. “Tell me what’s going to allow us to go back to a situation where we’re not in fear of getting and spreading this disease. And I think a lot of Democrats and a lot of moderate voters in California, are saying, ‘If it’s mandates, then so be it.’ “

Looming problems for both parties

Even if Newsom survives the recall election, the process could still signal some looming problems for Democrats. A big Election Day surge of GOP voters reluctant to vote by mail could produce a somewhat tighter finish than polls are forecasting. Democrats have been hurt in previous midterm elections by lagging turnout among young people and Latinos, two key party constituencies, and early returns show they are returning ballots at much lower rates than other groups in California; some, though not all, polls have also shown Newsom’s support among Latinos eroding compared with his initial 2018 victory.

“The data that we have worked off of illustrates that there is something happening in the Latino community in California that is not receptive to the traditional Democratic playbook and the buttons that they are used to pushing,” says former California GOP Chairman Ron Nehring, who is now advising former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, one of the Republicans running to replace Newsom.

Yet a Newsom victory at anywhere near the level that polls are now indicating would underscore the continuing obstacles Republicans face with the voters who compose the core of the modern Democratic coalition not only in California but also nationally: young people, non-White voters and college-educated Whites, particularly those in each group concentrated in the largest metropolitan areas.

Especially telling is how Newsom’s Covid response has evolved from his greatest vulnerability to his most powerful motivator for that Democratic coalition.

“This is the Covid election, and it has been from the beginning,” says Dan Schnur, a former Republican communications adviser who teaches political communications at the University of Southern California and the University of California at Berkeley. “It wouldn’t exist without Covid, and assuming Newsom survives, it’ll be because of Covid.”

Conservatives had launched multiple efforts to recall Newsom even before the pandemic struck last year, focusing on issues such as taxes, crime and undocumented immigration. But those efforts all foundered until Covid – and Newsom himself – provided a bolt of lightning. Last November, while the state was still largely in lockdown, the governor attended a dinner for a close political ally at the exclusive Napa Valley restaurant French Laundry; almost simultaneously a state judge, citing the logistical challenges Covid created, gave recall proponents more time to gather enough signatures to qualify for the ballot.

Newsom’s ill-advised dinner – at a time when his children were already attending an in-person private school – crystallized enough frustration over the state’s lengthy lockdowns and shifting policies to attract national Republicans to pour in fundraising help to the recall effort, and with the added time and resources, proponents met California’s low bar to qualify the recall. (To qualify for the ballot, the state requires a recall to attract signatures equal to just 12% of the votes in the previous governor’s election, the lowest level necessary in any of the 19 states with recall laws for governors.)

“There were several recall attempts at Newsom earlier in his term, but none of them really went anywhere until you had Covid,” says Nehring. “It was … the frustration with that erratic response that helped drive the recall to qualify.”

A gamble that’s likely to pay off

With the recall drawing its strength from voters opposed to Newsom’s stringent Covid measures, the governor initially sought to emphasize the state’s movement away from those restrictions. As vaccines became widely available, he set June 15 as a reopening day for the state, lifted most public health mandates and regularly touted what he called “the California comeback.”

“We had a trajectory that looked very good for us in the sense that Biden was talking about Independence Day [as a turning point], we had a clear stake in the ground to open the state on June 15, people’s attitudes were improving … and in May and June there was a pervasive feeling of optimism,” says Clegg, the strategist for Newsom’s campaign.

But the Covid surge driven by the Delta variant early this summer upended those plans. Once Delta emerged, Clegg says, the optimistic message of moving beyond Covid increasingly seemed “tone deaf” to the growing public concern, as well as to the public health reality of caseloads and hospitalization numbers that were again rapidly rising.

In response, Newsom made a fateful policy and political pivot. Following recommendations from his health advisers, Newsom imposed new mandates for vaccinations or regular testing on state employees and health care workers in late July, and a first-in-the-nation requirement for all K-12 teachers and staff in early August. In July he also imposed a statewide requirement for indoor mask-wearing at K-12 schools (while leaving implementation to local school boards). And he moved his support for those mandates – and the opposition to them from all the leading GOP candidates – to the center of his messaging against the recall, both in television advertising and public appearances.

Leaning into tough vaccine mandates amid a recall that was initially boosted by opposition to his stringent Covid responses represented a political gamble for Newsom. But unless all of the latest polls in the state are spectacularly wrong, it’s a gamble that has paid off – with potentially broad implications for the national debate over vaccine mandates. Newsom’s response to the Delta wave, says Clegg, “created a new line of scrimmage” in the contest that shifted the advantage toward the governor.

Polls suggest the debate over mandates has helped to solve the greatest problem Newsom always faced in the recall: the risk that Democrats – who outnumber Republicans in the state by about 2 to 1 – would slumber through it. That danger was underscored by a late July poll from the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California (Berkeley) that sent shock waves through the state by showing nearly half of likely voters backing the recall and Republicans far more engaged than Democrats. Now the latest surveys from Berkeley and the Public Policy Institute of California have found about three-fifths of likely voters opposing the recall and Democrats far more engaged than earlier this year.

Newsom’s huge spending blitz on advertising and organizing partly explains that shift, but California analysts also point to the governor’s success at converting the race primarily into a referendum on his policies to combat Covid.

What were for Republican voters “the reasons to remove the governor became for the Democrats the reason to keep him,” says Baldassare. “For Democratic voters … the Delta variant wave has created a sense of urgency and importance to this [recall] that it otherwise would not have had.”

Nehring believes the pivot point in the race wasn’t the governor’s embrace of Covid mandates, but the emergence of firebrand conservative talk radio host Larry Elder as the front-runner in the GOP field.

“What helped Gavin Newsom regain his footing is Larry Elder, more than anything else,” Nehring says. “You can literally see the trend line shift when Elder gets in the race and becomes the leading alternative. That forced people to reconsider how they would vote on [recalling Newsom]. Republicans were already energized against Newsom. But when Larry Elder got in the race it served to energize the Democrats.”

A lesson for other Democrats

But others note that, even amid all of Elder’s other conservative positions that present tempting targets in left-leaning California, Newsom has focused above all on the opposition from him (and the other top GOP contenders) to mask and vaccine mandates, while linking them to GOP Govs. Ron DeSantis in Florida and Greg Abbott in Texas, who have aggressively fought such requirements.

“Despite the fact that Elder is to the right of most Californians on many issues, it’s his approach to the pandemic that has helped Newsom more than anything,” says Schnur. “Newsom isn’t just running against Larry Elder and Donald Trump; he’s running against Greg Abbott and Ron DeSantis. He’s framed this as a choice not just between two candidates but between two very different approaches the states have taken in response to the pandemic.”

That’s clearly struck a chord, most powerfully for Democratic voters, but also for many independents (most of whom oppose the recall in the latest surveys) and even a sliver of Republicans. Both the latest Public Policy Institute of California and Berkeley polls found Newsom winning about two-thirds of likely voters who have been vaccinated, and the latter survey found that only about one-third of voters now say the state is doing “too much” to combat the coronavirus, the complaint that initially boosted the recall. That’s roughly the same meager share of the vote that Trump won in California while losing the state by more than 5 million votes.

Maybe the most striking thing about Newsom’s revival is that it’s come even as the Public Policy Institute of California surveys have found that the share of Californians who believe the state is on the wrong track has increased. That defies the usual laws of political gravity, which hold that incumbents almost always decline as “wrong track” rises. Newsom’s reversal of that trend points to his success at focusing voters’ attention not only on his own performance and current conditions but also on what Republicans would do if given power in the state, particularly in responding to the persistent coronavirus outbreak.

Newsom’s ability to shift voters’ attention toward the GOP alternative may present the race’s most important lesson for other Democrats. In the most immediate sense, despite all the visibility of vaccine opponents, he may offer more evidence that the GOP leaders almost uniformly condemning vaccine mandates are playing to the short side of public opinion. Even if California is particularly favorable terrain to contest that argument, the latest CNN national poll conducted by SRSS found roughly 55% majorities supporting vaccine mandates for students, office workers and attendance at large events such as concerts or sporting events. On each front, mandate support rose to about 70% among adults who have been vaccinated; that included more than 40% of vaccinated Republicans, according to figures provided by CNN’s polling unit.

More broadly, a solid Newsom victory might move the needle in the internal Democratic debate over how to run in 2022. The dominant view in the White House and the party leadership is that Democrats should run next year primarily by stressing their legislative successes: the new programs for infrastructure, clean energy, education and health care, as well as the expanded tax assistance for families with children, that they hope to pass this fall. A minority view in the party says Democrats are more likely to prevent the usual midterm turnout falloff among voters in the president’s party by stressing what Republicans will do if they regain power.

Clegg says Newsom’s recovery in the recall lays down a clear marker for the latter approach: “We really did wake up this blue giant, and that’s what we have to do in 2022.”

Clegg wants Democrats to focus next year not only on the Republican opposition to mask and vaccine requirements for Covid but also on the risk that a congressional GOP majority would take steps that could allow Trump or another Republican nominee to steal the 2024 presidential election.

“Put me,” he says, “violently in the camp that says Democrats really need to make this cycle about the stakes if these guys win.”

More Democrats may join him there if Newsom decisively turns back the recall on Tuesday.