Liliana Silva didn´t see it coming. When her brother traveled from Germany, where he lives, to visit his family in Chile, none of them felt vulnerable. He had completed the 10-day mandatory quarantine in Santiago and shown no symptoms of Covid-19.

Yet, less than a week later, her parents, her three daughters and an aunt were infected with the Delta variant. She and her husband weren´t spared. Soon, they also felt unwell. Nearly everyone had mild symptoms, lasting from 2 to 4 days – except for her father and children.

“My father suffers from chronic leukemia; he had pneumonia, got dehydrated and was hospitalized. If he hadn’t gotten his shots, he would have died,” she said, referring to the Covid-19 vaccine.

Her children, however, were too young to have been vaccinated, and suffered badly from the infection. “My daughters went through high fever, coughing, vomiting and bad headaches. I wish they had been vaccinated; I was in constant fear for them,” she said.

Since Chile started immunizing its population against Covid-19, last February, it has been internationally praised for its smooth and successful vaccination campaign. According to the health ministry’s latest reports, almost 87% of eligible Chileans are fully vaccinated.

That’s a figure that positions this South American country among the nations with the highest share of people immunized. Chile also stands out compared to the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, where 75% of the regional total population had yet to be fully vaccinated as of Sept 1, according to the Pan American Health Organization.

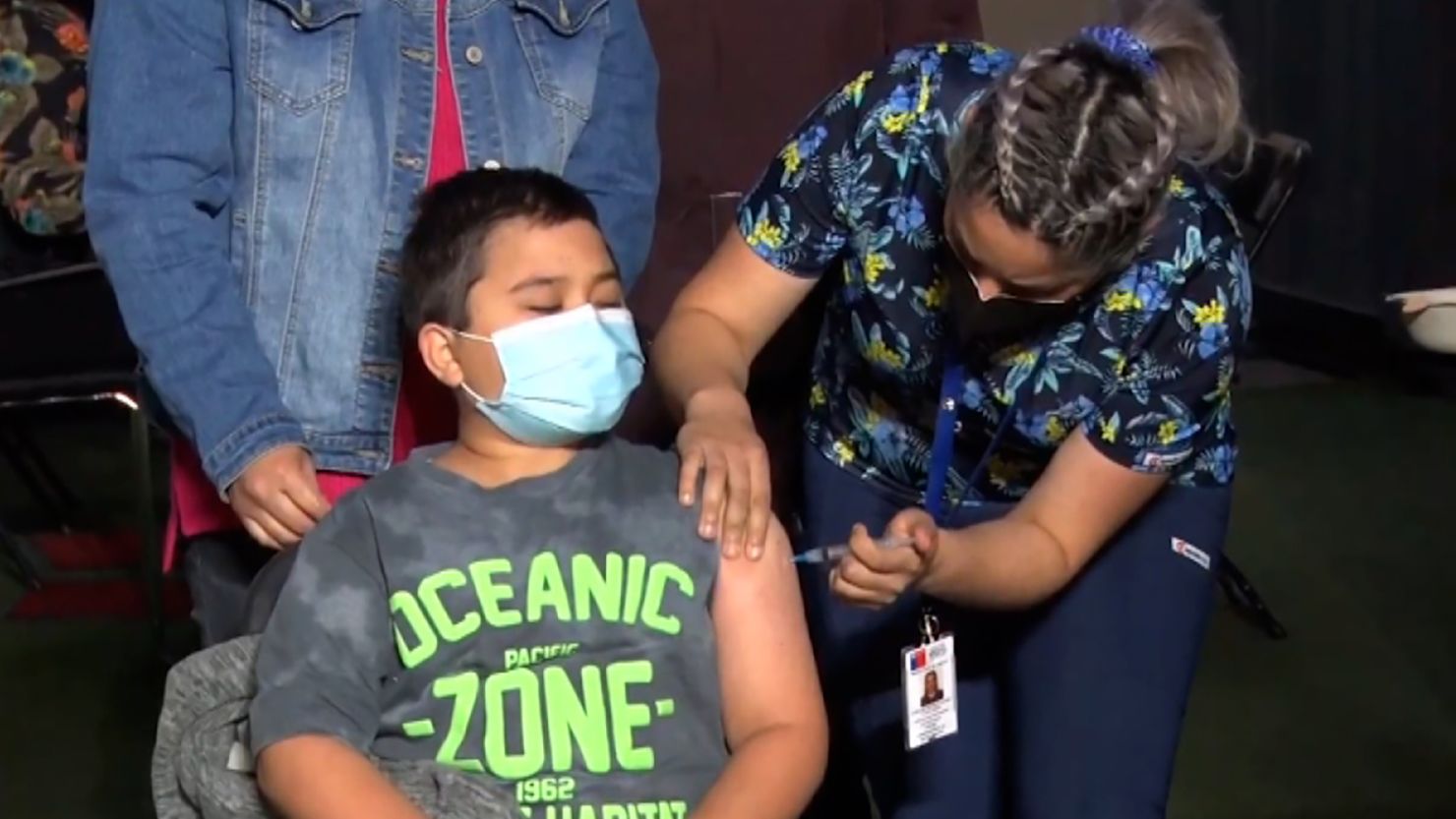

The high immunization coverage has led to decreasing infection rates, but Chile doesn’t plan to cut back precautions, or ease its vaccination drive. Last week, the government announced that Chile would become one of the few countries in the world to approve vaccination with CoronaVac for children between the ages of 6 and 11. Inoculations started on Monday.

“It is known that in countries where most of the adult population has been immunized, the coronavirus starts targeting those who remain more vulnerable and kids get more infected, as is happening in the United States,” says Dr. Lorena Tapia, a pediatrician and infectologist from the Universidad de Chile and a member of the advising committee on vaccines for the Science Ministry.

“We must move forward with immunization among the youngest.”

An early strategy

Different elements explain Chile´s successful vaccination rate. Authorities started planning a response to the pandemic very early on. In May 2020, two months after the country reported its first Covid cases, the Ministry of Science began negotiating contracts with different labs – Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sinovac (which makes the Coronavac), and CanSino – to secure the purchase of shots for all Chileans.

Simultaneously, the institution worked on having the local scientific community take part in Phase 3 clinical trials, which would give the country priority in the supply of vaccines. Ultimately, commercial deals were closed promptly.

“From the beginning, our campaign was based on the advantages of having a diversified portfolio of vaccines,” says Minister of Science Andrés Couve.

“That allowed us not to depend on the availability of one provider only, considering the high demand there is for anti-Covid doses globally,” he adds.

That strategy, combined with an overall historically well-organized vaccination system, the setting up of 1400 new inoculation sites and an easy-to-access scheduling system by eligible groups, has allowed the country’s vaccination process to move forward with few interruptions.

It helps that Chile has a small population. And its relatively low debt and long-time responsible fiscal policy also mean enough funds to buy sufficient vaccines. The country’s political and economic stability has even attracted Chinese investments: Sinovac recently announced it will open a vaccine factory near Santiago next year.

So far Chile has received 36 million doses for a population of 19 million, enough to have already started distributing booster shots. Every week, a new group of people become eligible for the boosters – this week, the country is giving booster shots to people ages 55 and up.

“It’s very easy to get vaccinated in Chile and people have been very responsible. The anti-vaccine movement is marginal,” says Eduardo Undurraga, a former researcher at the US CDC and current professor at Universidad Católica de Chile.

Chileans have historically relied on immunization campaigns, and vaccine skepticism has not taken deep root in the country. In fact, Chile eradicated smallpox 27 years earlier than the rest of the world and was the third country to control polio. Citizens’ trust in vaccines has also allowed to significantly reduce childhood diseases such as measles, mumps, and rubella.

Undurraga was part of the team leading an evaluation of the effectiveness of the CoronaVac inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, using a massive prospective cohort of approximately 10 million individuals in Chile. The study was commissioned by the country’s health ministry after the international community raised doubts about the efficacy of maker Sinovac’s formula, which has been the backbone of Chile’s immunization campaign.

The results, released in early July, were reassuring: the study found that its effectiveness was about 66% for prevention of Covid and around 90% for the prevention of hospitalization, ICU admission and death. However, this investigation was done before the first cases of Chileans infected with the Delta variant were reported in late June.

Staying vigilant

While Covid-19 figures are surging again in Central America and the Caribbean, in the past week Chile reached its lowest infection rate and number of active cases since March 2020.

The percentage of nasal and throat swabs with positive results has stabilized at less than 1%, which led the government to progressively loosen confinement restrictions … somewhat. A 10 pm curfew that has been in place since last year, for example, has shifted to 12am – enough to allow some Chileans to feel they are finally getting some freedom again.

Immunologists and epidemiologists, however, insist on the need to stay vigilant. They are particularly concerned about the Delta variant, which has been circulating for a few months now.

Between the end of February and late July, Chile went through a dramatic wave of Covid-19, with daily new infections reaching up to 9,000. At that time, vaccination had just started, and the coverage was too low to have an impact. Chileans, however, felt safer and stopped following some self-protection measures. Experts also attributed the spike of Covid-19 cases to holidaymakers’ travel.

Since then, broad vaccination has played a key role in preventing a new outbreak, experts say, but it isn’t enough.

That’s why the government has never fully lifted prevention measures, in contrast to other countries which eased social distancing rules after experiencing a decrease of confirmed cases, then saw infections surge. Face mask wearing is still enforced, as is social distancing in public places and schools. Borders are not fully open again and travelers still face significant restrictions.

Those actions have allowed Chileans to keep the Delta strain in line until now. But with Covid-19, uncertainty always prevails.

“We can’t say it is under control,” says Dr. Alexis Kalergis, director of the Millennium Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy in Santiago. “The pandemic isn´t over and if we´re not careful we can have a new outbreak at any time.”

Despite being cautious about attributing decreasing infection rates merely to the immunization process, Kalergis said that expanding vaccination even further is the best way to avoid the appearane and spread of new strains.

A vaccine for children

In this context, vaccinating the youngest seems like the natural next step for Chile to preserve its success. As pediatric hospitalizations spike in some countries, including the US, Chile is racing to escape from that path.

Dr. Catterina Ferreccio, an epidemiologist who serves on the Health Ministry´s Covid-19 Advisory Committee, explains the urgency: At this stage of the pandemic, she says, kids are likely to become a reservoir for Covid-19, which is risky for them and the rest of the community. There could be at some point, a new variant that beats their natural defenses.

Dr. Lorena Tapia, the pediatrician, shares that concern. She also points out that in this country 52% of children in school age are overweight or obese, which increases their risk of severe illness and even death from Covid. There is also a significant number of children with respiratory diseases.

“It may be true that most kids will do well if they´re infected, but several of them won’t. And today, with the safety data we manage, it is something we can prevent.”

Last Monday, Ferreccio took part in Covid-19 advisory committee’s meeting to assess approving the CoronaVac vaccine for children between 6 and 11. She says that the decision was taken on the basis of reliable data provided by China, where more than 40 million kids in that age range have been inoculated with CoronaVac, and on Chile’s own long experience with this kind of vaccine.

“This is a well-known vaccine platform; we are not experimenting. It is very safe, and we have seen that when the children are protected, we are all protected against new strains,” she says.

Plus, getting kids back to school is an important public health measure in itself, she says.

“As a grandmother of 5, I´ve seen how hard it´s been for [children] to stay at home, and it gets worse in lower income families,” says Ferreccio, the epidemiologist.

“We have seen domestic violence rates swell and it’s damaging children tremendously. For many kids school is a protection. Vaccinating them will calm the fears of parents, teachers, and epidemiologists. We can’t wait any longer.”