President Joe Biden tried twice last month to get to his beach house on the Delaware coast. He never made it.

Far from relaxing, the 31 days of August were the longest and most wrenching of Biden’s presidency. A month his aides once viewed as a launching pad for an ambitious autumn was instead consumed by mayhem in Afghanistan, a worsening pandemic and, as it concluded, a massive hurricane plowing into the Gulf Coast.

A domestic agenda the President once hoped to spend August discussing still inched forward. But Biden’s handling of chaotic and unplanned-for events dominated his time and the nation’s attention.

After a frantic two-and-a-half week airlift, the last US troops left Afghanistan on Monday, fulfilling the President’s promise to end America’s longest war. Yet the process of getting there, including the administration’s admission it had been caught off-guard by the speed with which the Taliban overtook the country, undercut Biden’s vow to restore competence to government.

A simultaneous surge in Covid-19 cases, fueled by continued vaccine hesitancy and the highly contagious Delta variant, has nudged the country back toward mask mandates and limits on gatherings – a distant cry from the “freedom from the virus” Biden sought to project on July Fourth.

It’s far too soon to know whether the last four weeks will be the most consequential of Biden’s presidency. They will eventually amount to only a little more than 2% of his entire first term. Yet the lingering challenges facing the White House in September, October and beyond already loom large, with the administration trying to keep its domestic agenda on track even as it grapples with the fallout from Afghanistan.

The forceful tone of Biden’s national address Tuesday was intentional, officials said, as was the lengthy nature of the speech. The President’s remarks served as an effort to punctuate the end of two decades of war and they underscore a decision Biden never wavered from. But it was also a clear, if implicit, signal that the White House would publicly move its focus to the domestic challenges at hand in the days ahead, according to multiple administration officials.

The speech was, as described by one official, “a clear reminder to the public of the bigger picture” – one Biden intensely believes carries a wide swath of support inside the country. Still, officials acknowledge there are still significant challenges ahead.

Congressional inquiries into how the administration was caught flat-footed for the fall of Kabul are set to begin soon, and even some Democrats are poised to press top officials for answers in public hearings. And the administration’s own “hot wash” review of what happened is designed for immediate answers on whether signals were missed in the lead-up to the Taliban’s takeover.

Tests also still await Biden in extracting the 100 to 200 Americans who remain in Afghanistan, not to mention the thousands of Afghan allies who assisted the US’ war effort but were unable to leave during the frantic airlift.

Of the Americans who remain in the country, sources say they represent the most complex cases US officials were seeking to manage in the final days. Most were dual citizens, often long-time residents of Afghanistan, who wavered on whether to leave until the final moments out of concern for leaving extended family.

“There’s a lot of work ahead, no question about it,” one US official said. “We’ve gotten positive signals, but things are just very fluid at this stage.”

The punishing days of August, above all, underscored the brutal reality of how all presidents are ultimately judged by events thrust upon them, rather than the scripted moments on meticulously planned political calendars. At the center of it all are fresh questions about how the administration’s overall competence will ultimately be viewed by the American public.

“There is less room for error on future crises,” one top ally, who speaks frequently to Biden, told CNN. “The best way to show competence is to execute and manage all of this with confidence and demonstrate results.”

Now, publicly at least, the expectation is for a clear shift in focus in the days ahead.

Shortly after Biden’s remarks, the White House released his schedule for Wednesday. For the first time in more than a week, there would be no Situation Room meeting with his national security team set for the morning.

Momentum derailed in the dog days of summer

In meetings in July, Biden’s senior advisers plotted the best ways to harness their momentum heading into the fall. Chief of staff Ron Klain impressed upon the West Wing team the critical importance of the weeks leading up to Labor Day, as two of Biden’s chief priorities – a bipartisan infrastructure plan and a more ambitious social policy bill – made their way through Congress.

Officials said in mid-July that Biden himself planned to tighten his focus on popular elements of a sweeping legislative agenda that were hanging in the balance, hoping to sway Americans in red-leaning areas. He had made clear his desire to avoid what he saw as a mistake during his tenure as vice president, when, Biden said, then-President Barack Obama didn’t take his advice to hit the road and explain their administration’s agenda to the American people.

The White House started August with a triumphant head of steam, eager to take an early victory lap on Senate passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill. A bus tour featuring a marquee roster of top Democrats was set to travel the country, drawing attention to the party’s agenda. A “war room” was stood up by White House aides, meant to coordinate messaging on the President’s economic agenda.

The Senate did approve the infrastructure package – four days before the Taliban arrived in Kabul. The administration’s efforts to tout the package out in the country ultimately received little attention, despite early assertions from officials that the economic proposals would remain the priority of the West Wing.

Now top Cabinet officials and the President’s senior advisers are working to keep the agenda from being set back by criticism of how the Afghanistan withdrawal was executed.

Biden himself has sought to help in those efforts. When he emerged after meeting with other Group of 7 leaders to discuss Afghanistan last week, he spent more than five minutes at the start of his remarks discussing his legislative agenda before getting to his decision to stick with an August 31 deadline to withdraw troops.

New daunting challenges begin to mount

Perhaps the most lasting impact from the month of August is how it heaped significant new challenges on the administration’s plate, from a humanitarian crisis among Afghan refugees to a still-developing crisis along the Gulf Coast in the wake of Hurricane Ida and the stubborn fight with Covid-19 and the dangerous Delta variant.

Plans are being made for the President to travel to Louisiana – a trip that could take place in the early days of September, aides say, depending on conditions on the ground – in the first of many ways the administration can showcase its ability to manage a crisis.

The President also plans to play a prominent role in commemorating the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, though officials concede the milestone is now fraught with fresh grief and new questions about how America’s longest war ended.

And Biden is expected to visit California for the first time in the coming week to campaign for Gov. Gavin Newsom, who is facing a recall election. The crisis in Afghanistan already scrambled the White House’s efforts to assist Newsom ahead of the September 14 recall vote when Vice President Kamala Harris was forced to scrap a planned campaign stop after 13 US service members were killed in a terror attack last week, along with at least 170 others.

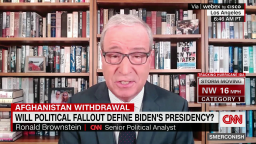

The broader political consequences of Biden’s actions throughout the days of August remain an open question.

Some House and Senate Democrats watched the President’s handling of the withdrawal from Afghanistan with growing alarm, distancing themselves from the White House as some Americans were left behind. Even some of Biden’s legislative allies are faulting the administration’s handling of the situation and saying they need answers about the deadly end to the US’ longest war.

“Leaving any American citizen behind is unacceptable, and I will keep pushing this administration to do everything in its power to get our people out,” said Sen. Mark Kelly, an Arizona Democrat.

Sen. Maggie Hassan, a New Hampshire Democrat who – like Kelly – faces a difficult reelection, told WMUR last week that there have been “real miscalculations” by Biden’s foreign policy team, saying there shouldn’t be “artificial timelines” set for the withdrawal.

Biden’s defiant streak on full display

The President has been eager to take credit for the airlift of more than 120,000 people from Afghanistan, even as he faces sharp criticism for how the administration was so blindsided by the rapid fall of the democratic Afghan government.

On Tuesday, delivering a vehement defense of his decision to withdraw from the country, Biden appeared eager to assume the mantle of the president who was finally able to end the war, an achievement his two predecessors promised but couldn’t deliver.

“I refuse to send another generation of America’s sons and daughters to fight a war that should have ended long ago,” Biden said.

Ultimately, the President and his advisers believe Americans’ disapproval of the chaos that surrounded the end of the war will eventually fade into acceptance that it was time to leave Afghanistan. Americans continue to support the US withdrawal while expressing serious concerns about the way it was handled, recent polls have found.

A Pew Research Study conducted August 23-29 found 54% of US adults said withdrawing US troops from Afghanistan was the right decision, and 69% said the US mostly failed in achieving its goals in Afghanistan. Just 26% said the Biden administration did a good or excellent job handling the situation there.

White House officials still believe the President will ultimately be judged by the handling of the economy and the pandemic. Advisers to Biden are eager to steer the conversation back to both of those topics, which underscores just how uncertain the political perils of Afghanistan are for the commander in chief.

“Addressing crises is what government is supposed to do. It’s what any president is supposed to do, what any vice president is supposed to do and what the senior members of a president’s team are supposed to do,” press secretary Jen Psaki said this week.

“When you have moments like this where you are facing, as you said, multiple crises – I would add, of course, that we’re continuing to fight a pandemic that continues to take the lives of thousands of people every week – you have to rely on strong and capable team members, you have to be nimble enough to adapt quickly.”

“I think we would argue this is actually government working to do our best to function as best as we can,” Psaki added. “Is it tough? Yes. Are the days long? Yes. Is it always going to be perfect? No. But this is exactly what government is supposed to be doing.”

Presidents are often happy to turn the calendar to September

Augusts are historically perilous terrain for presidents, particularly in their first years in office as a post-inauguration honeymoon period fades.

Biden White House

It was in August 2009 when angry conservatives formed the tea party movement in opposition to President Barack Obama’s proposed health care law, forcing his White House to rethink its approach to getting the Affordable Care Act passed. At the same time, Obama was weighing a surge of troops to Afghanistan, despite having promised voters a year before that he would end the war.

Eight years later, in August 2017, President Donald Trump engaged in a standoff with North Korea from his Bedminster, New Jersey, golf club, from which he promised to rain “fire and fury” on Kim Jong Un. At the end of the month, he ignited outrage by claiming there had been good people “on both sides” of deadly White nationalist protests in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The month also comes as the yearly hurricane season is reaching its peak, when storms pounding the East or Gulf coasts can quickly turn into tests of presidential leadership – as Hurricane Katrina did in August 2005. And the month’s congressional recess can often prompt a shift in the political winds as lawmakers face constituents back home.

Biden and his team remained mindful of the historic pitfalls, according to one official, who said the message to staff at the start of the month was to allow for flexibility when planning summer vacations. That wound up being prescient advice not only for senior aides, some of whom were forced to scrap family getaways, but also for Biden himself.

After going back-and-forth between the White House and Camp David as Kabul fell into Taliban hands, Biden canceled his remaining plans to visit his Delaware homes in Rehoboth Beach and Wilmington.

Instead, he remained in Washington for two weekends straight – the longest stretch he’s remained at the executive mansion since taking office.