Amid a deadly summer of flooding in different parts of the world, scientists have found the number of people at risk to extreme flooding has grown significantly in the past two decades.

In Germany, severe flooding claimed the lives of at least 173 people. In Nigeria, Lagos Island experienced one of its worst floods in recent years, submerging cars and houses. And, earlier this week, officials announced that the death toll from China’s July floods had climbed to 302 – more than triple the previous estimate.

Climate change is making extreme flooding worse, and a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature concluded the population exposed to those floods since 2000 is 10 times higher than previous estimates, as more people migrate into flood-prone areas.

“It’s not surprising that we’re seeing really large floods that are potentially unprecedented affecting countries like China,” Beth Tellman, lead author and co-founder of Cloud to Street, an analytics firm that developed the Global Flood Database used as the backbone of the new research, told CNN. “This is exactly what the climate models have predicted.”

The study comes days before the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is set to release a major “state of the science” report, which is expected to describe how extreme weather such as floods, cyclones, and sea level rise will continue to worsen and become more frequent due to human-caused climate change.

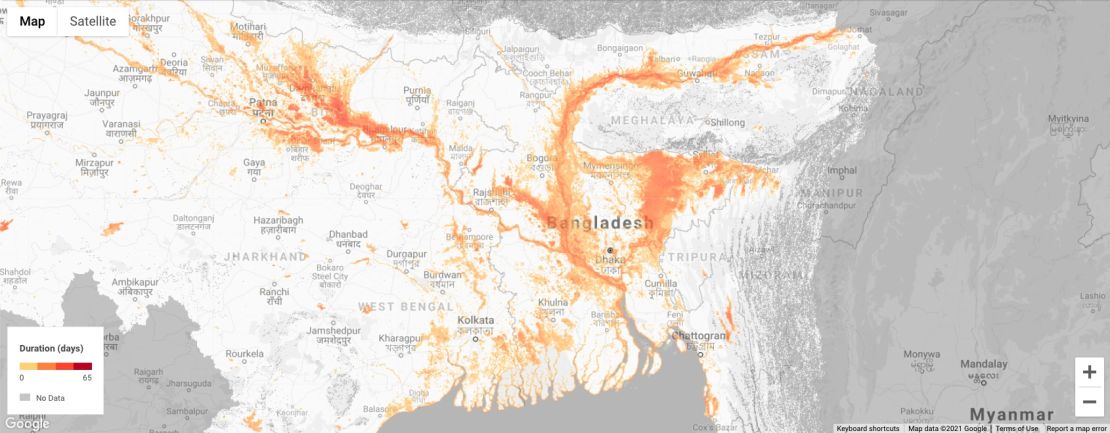

Scientists at Cloud to Street, NASA, Google Earth and universities analyzed global flood exposure using satellite observations, creating the largest flood data set ever produced that maps the maximum extent of water during 913 large flood events between 2000 and 2018.

“It’s great to have such a database that you can now test your model against, especially at a global scale,” Guy Schumann, a research scientist not involved with the study, who specializes in flood data and modeling, told CNN.

“Everybody now wants to know what’s going on globally, whereas traditionally, these databases or observations were only available at field measurement scales of a local or, at best at a national scale.”

Using the database, scientists pinpointed where major flooding events have happened in the last two decades. They found that nearly 90% of flood events were in South and Southeast Asia, particularly in China and India – places where migration has increased significantly since 2000.

Tellman, who has been working on this research for the past five years, said it “was shocking” to see the increase in flood events where population has also skyrocketed. And floodplains are now more frequently found in urban areas, she said.

“That was sort of the big ‘aha!’ moment for us,” Tellman said, “where we’re like ‘there is a really serious problem with floodplain-prone development.’”

From 2000 to 2015, approximately 58 to 86 million people moved to flood-prone regions, they found, which translates to a roughly 20% increase in the population exposed to floods. Flooding and the number of people exposed to it will continue to worsen, the study found. Thirty-two countries are already experiencing increasing floods, and 25 new countries will be added to that list by 2030 unless greenhouse gas emissions are significantly curbed, researchers found.

Low-income communities are often the most at risk, since they tend to have no choice but to settle in less-favorable, less-expensive areas that are more prone to flooding.

“It’s not like people are necessarily wanting or choosing to live in a place at high risk, but they may have no other option or no public housing program in their country,” Tellman said.

In 2007, for example, floods from a deadly cyclone killed roughly 1,000 residents and displaced 9 million people in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Within that time frame, the analysis shows Dhaka also experienced a surge in population in poor areas prone to inundation.

Beyond flooding from heavy rainfall, tropical storms and melting snow, the database also accounts for flooding caused by dam failures. While they represented less than 2% of flood events, dam breaks had the highest increase in occurrence from 2000 to 2015 – 177% – that exposed vulnerable populations. Tellman said it’s probably because of what hydrologists call the “levee effect.”

“When we have infrastructure like a dam or levee, people feel safe and feel like that land is protected, so it increases in value, and we build things there,” she said. “The problem is, if the dam isn’t maintained, then it can become a massive hazard and affect so many people.”

In 2008, embankments along the Koshi River collapsed and destroyed the homes of more than 3 million people in India and Nepal. In 2018, heavy rain and a subsequent release of water from the Bagre Dam in Burkina Faso flooded thousands of hectares of agricultural land in the neighboring country of Ghana, which worsened food insecurity in the region.

Researchers say such incidents demonstrate the deadly cost of failing infrastructure, exacerbated by climate change.

Philip Ward, a professor of global water risk dynamics at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, told CNN the study’s findings emphasize the importance of maintaining aging infrastructure and strengthening resilience. He also said the results suggest officials should put more resources into warnings.

“We need to make sure that there are still early warning systems, evacuation plans and good communication between the most vulnerable, political officials, emergency responders, and so forth,” said Ward, who was not involved with the study.

Satellite observations capture realities that are not often captured by predictive climate models, according to Tellman.

Most maps of flood-prone areas, including those used by government agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency, rely on models that simulate floods based on historical data, the results of which can be limited as climate change pushes flooding into unprecedented territory.

Outside experts said Cloud to Street’s population analysis will strengthen the data they already have, especially as the climate changes.

“The most important thing from this research is the database itself,” Ward said. “As somebody who models flood risks, these data really will allow us to better validate the models and check the models against reality.”

As climate change fuels more extreme and far-reaching floods, Tellman hopes the new analysis will encourage policymakers to invest in equitable climate adaptation measures in places where flood exposure has grown faster than the surrounding population.

“Who gets impacted by floods really is in our control,” Tellman said.