Whether Neanderthals thought symbolically and had an artistic sensibility has been a question that has vexed experts in human evolution.

But evidence is mounting that our Stone Age cousins were our cognitive equals and created forms of art in Europe long before Homo sapiens were on the scene.

A new study of a rock feature stained red in a cave in southern Spain has concluded that the red pigment – made from ocher – was intentionally painted, most likely by Neanderthals, refuting earlier research that said the red marks were natural.

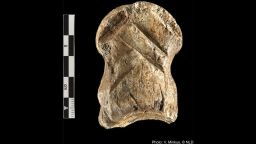

The markings, which date back to more than 60,000 years ago, were made on a massive stalagmite 328 feet (100 meters) into Cueva de Ardales near Málaga. The stalagmite’sdomelike shape was formed by pillars of mineral deposited by water, and the markings were made inside folds of rock that resembled drawn curtains.

The researchers analyzed samples of the red residues and concluded that the ocher, a natural pigment found in clay, used to make them was brought to the cave from somewhere else – although the study did not determine exactly from where.

This suggested the pigment had to “be collected, transported and prepared in advance of entering the cave, implying deliberation and planning, which are additionally implied by the need to have adequate lighting,” said study author João Zilhão, an ICREA (Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies) research professor at the University of Barcelona and the University of Lisbon.

The authors said it wasn’t art in a narrow sense – an image or object that is beautiful or expresses feelings – but was likely a way to mark a place that was symbolically important to them.

The researchers believe “the dome is the symbol, and the paintings are there to mark it as such, not the other way around,” according to the study, which published in the journal PNAS Monday.

Underground world

The study compared the red-stained rock formation to Bruniquel, a site in France, where mysterious circular structures made from stalagmites were found 984 feet (300 meters) inside an underground cave in France. Wrenched from the cave floor and meticulously put together more than 175,000 years ago, their discovery suggested experts may have previously underestimated the abilities of the early human species.

“All we can say with certainty is that the underground was important to them. We can also speculate that, with all likelihood, it was for mythological reasons,” Zilhão said.

Cave paintings and artifacts like painted seashells have long been regarded as the work of early modern humans, and it’s only with the advent of new dating techniques that some have been recognized – sometimes begrudgingly – as the handiwork of Neanderthals.

Alistair Pike, a professor of archaeological sciences at the University of Southampton, explained that there had long been a “juxtaposition between humans as artistic thinkers and Neanderthals the dumb knuckle-dragging brutes.” He wasn’t involved in the latest study but said it was convincing.

“This is how they were portrayed in a number of paintings and sculptures in publications and museums in the early 20th century, and these stereotypes persisted despite there being very little evidence for either,” he added in an email. “The question of Neanderthals’ symbolic capabilities has been very contentious, but this stems back to outdated and racist nineteenth century ideas.”

Named for the German valley where their remains were first discovered, Neanderthals roamed Earth for a period of 350,000 years.

Researchers believe Neanderthals overlapped with modern humans geographically for a period of more than 30,000 years after humans migrated out of Africa and before Neanderthals went extinct about 40,000 years ago – although some scientists think it could have beenas little as 6,000 years of overlap. Sometimes when the two groups met, they had sex and gave birth to children, leaving Neanderthal traces in most people’s DNA.

Scientists had previously suggested that the markings in the Spanish cave were the result of natural processes such as the iron oxides deposited by dripping water or accidental contact from someone with red pigments on their skin or clothes. But the team behind the new study said their analysis showed that this was not the case.

Only a small area of the stalagmite, which was located in a large cavern, was colored and there were no similar markings elsewhere on the cave walls, they said.

The researchers believe that the markings were made by spattering the paint – possibly chewed pigment blown out through the mouth or by using a bone as a kind of straw, said study coauthor Francesco d’Errico, a director of research with the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and professor at the University of Bergen.

The scientists also found that at least two different pigments were used to make the marks and at different points in time, suggesting the stalagmite dome was used symbolically over an extended period.

“The dating of the flowstone is consistent with the hypothesis that Neanderthals repeatedly visit the chamber in which the flowstone is located to, we argue, symbolically mark it, hence demonstrating that we are dealing with a long term symbolic tradition,” d’Errico said.