When Jessica Roberts heard that a fire ignited roughly 4 miles from where the Camp Fire started in 2018, she was catapulted back to the most traumatic experience of her life.

The Dixie Fire is California’s largest active wildfire, having burned more than 240,000 acres of land — an area larger than New York City — over the course of two weeks. Its size jumped significantly last weekend when it merged with the Fly Fire in the Lassen and Plumas national forests. More than 7,800 residents across Butte and Plumas counties have been ordered to evacuate as of Monday morning.

In the last few days, the smoke, orange skies and firefighting helicopters flying over the remote town of Paradise reminded residents of the deadly disaster that scarred the region — physically and emotionally — not so long ago. The Camp Fire was the deadliest wildfire in California’s history, killing 85 people and destroying the town of Paradise.

The Dixie Fire on Friday was just 23% contained, according to Cal Fire. Officials say the state’s worsening drought and low precipitation levels, fueled by climate change, are making it hard to fight the fire, which threatens more than 10,000 structures in the region with more than 60 already destroyed.

Even though Paradise is not directly threatened by the Dixie Fire, its proximity is unnerving. With a historic drought plaguing California, exacerbating what already looks to be a severe wildfire season, climate change is rekindling trauma and threatening the lives of those who have tried to escape its consequences.

Dozens of households displaced by the Camp Fire, like Roberts and her family, have already relocated elsewhere in the state, but many moved to nearby towns that are now in the fire’s path.

Each day the Dixie Fire burns, the anxiety grows along with it.

“Once you’re a fire victim of such magnitude, which I was and others have been, we watch these fires very closely,” she said. “It’s not something that we can get away from, because of the post-traumatic stress of it all.”

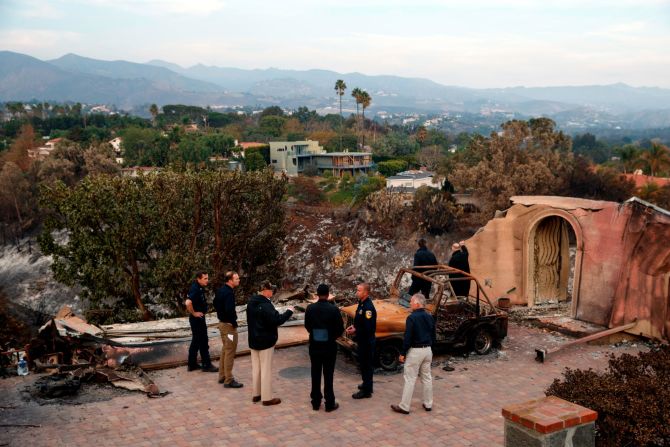

In pictures: Wildfires tear across California

Roberts lived in Magalia, just north of Paradise, when the Camp Fire engulfed the region. Her then-husband was out of town, so she evacuated with her 1-year-old son, 6-year-old daughter and their three dogs.

“I remember my daughter asking if we were going to die,” Roberts told CNN in tears. “And we weren’t even anywhere like some folks that were trapped in the flames. But the fact that my daughter asked if we were going to die that day still resonates.”

Roberts ultimately lost her home to the fire and, like many others, took what was left of her family’s former life to trailers and hotels. After months of moving she now lives in Sacramento, which is facing water shortages from the extreme drought.

Julian Martinez had a different idea. After sleeping in his truck for several months after the Camp Fire obliterated his home, he went back and bought a house in Paradise. Martinez manages a construction company that rebuilds houses in Paradise. Because of the swath of smoke blanketing the area, the company’s concrete deliveries — many for houses that are being rebuilt after the Camp Fire — have been postponed.

“It’s difficult,” Martinez told CNN. “Building a house is a hard project anyhow, and because these are rebuilds for people who lost their home, there’s a bit of added trauma and emotional challenges that come with that.”

Some who moved to nearby towns like Chester or Almanor, which are now threatened by the Dixie Fire, are being asked to evacuate again and reliving horrifying memories.

“That’s got to be so defeating to be experiencing that again,” said Martinez, who fears that another wildfire could still strike Paradise this season. “I sleep very lightly. Every time I hear a siren, I jump up and turn on the scanner and start listening to the fire reports and radio traffic.”

The cause of the Dixie Fire is still under investigation, but in a report filed to the California Public Utilities Commission, Pacific Gas and Electric said its power lines may have played a role.

PG&E reported one of the utility’s repairmen was sent to an area along Highway 70 on July 13 to investigate an outage at a hydropower dam on the Feather River. From a distance, the repairman reported seeing a “blown fuse” on a power line in an area that was “challenging” to reach, the utility reported.

Hours later, when the employee arrived at the scene, two fuses were blown and there was a fire at the base of a tree that was leaning against one of the company’s electric poles, the report says.

Camp Fire victims are watching in shock as another fire that may have been sparked by the utility burns down homes and upends lives. Investigators with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection found in 2019 that electrical lines owned by PG&E started the Camp Fire amid extremely dry and windy conditions.

In June 2020, PG&E pleaded guilty to 84 separate counts of involuntary manslaughter and one felony count of unlawfully starting a fire in the deadly case of the Camp Fire in 2018, which destroyed nearly 19,000 buildings.

“With the victims watching other victims watching what’s going on with the Dixie Fire, and knowing the fallout and what those folks are going to have to go through — and some of those folks are from the Camp Fire, which is a double experience for them — is ridiculous,” said Roberts.

In addition to a $3.5 million fine paid to prosecutors, the maximum amount allowable, the utility company also agreed to a $13.5 billion settlement to compensate victims of the Camp Fire and other fires. But Martinez says he and others have not yet received preliminary payments.

“The really unfortunate part is that for a lot of people up here, they didn’t have insurance, they lost their jobs, and they lost their homes,” Martinez said. “And they really needed money two and a half years ago. Some sort of payout earlier could have really made the difference.”

Martinez worries PG&E may suffer more penalties for the Dixie Fire, which could delay the payments even longer.

“We’re coming up on the third anniversary of the fire already,” Martinez added. “For a lot of people, they just got left with nothing — and those are the people that really should have been taken care of financially earlier, but way too much time has passed.”

A PG&E spokesperson told CNN: “We funded the trust in accordance with our plan of reorganization. PG&E is not involved in distributing trust funds.”

“We continue to honor the victims of the Camp Fire and previous fires, and all that was lost, by continuing the important work to reduce wildfire and other risk across our energy systems,” the spokesperson added.

In a rapidly changing climate, wildfires are becoming more severe and more frequent across the West. Roberts believes that should be a forefront issue and addressed with urgency.

“We’re only given one Earth that gave us everything to survive,” Roberts said. “Yet year by year, we are literally destroying it.”

She also hopes corporations who continue to ignore the climate crisis understand the emotional and economic toll repeating disasters like wildfires have on survivors, particularly those who still live in vulnerable communities.

“There are ways to have the least environmental impact as possible such as green energy without endangering the lives of the citizens that it serves,” she said. “I just really want people to not forget the victims, and that their voices be heard.”