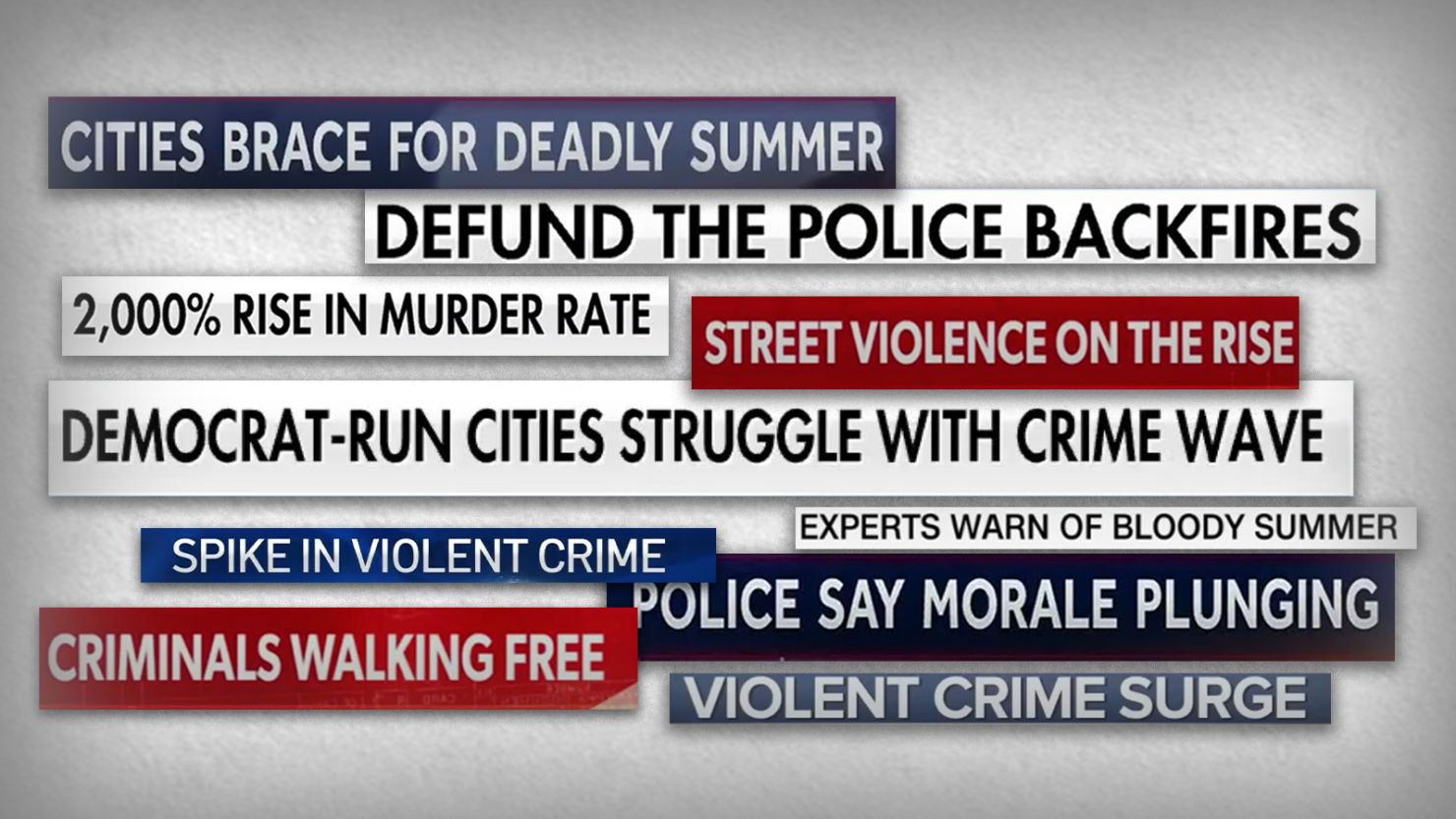

As Covid-19 rates improved and vaccinations allowed much of the country to reopen, reports of crime waves began to dominate headlines. Politicians, pundits, journalists and law enforcement have all scrambled to make sense of increased violence around the United States, while the public is left to sort through alarming numbers and conflicting narratives.

Understanding crime trends requires nuance, but gaps and inconsistencies in the data make it easy to misinterpret and spin facts in a way that serves political agendas instead of evidence-based solutions.

It’s never simple to pinpoint the reasons behind a rise in crime — especially following a year as extraordinary as 2020, in which Americans faced a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, a steep rise in unemployment rates and a summer of intense social unrest.

“Every time there’s a rise in crime, it’s complicated,” said Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. “As journalists, we should be putting all the complexity about this front and center.”

So here’s what you need to know to navigate the numbers — and what we actually know and don’t know about crime in the United States.

What we know

Only specific crimes have increased. It’s important to be clear about what types of crime are on the rise. Several forms of property crime, including robberies, residential burglaries and larceny declined in 2020 and continued to go down in the first quarter of 2021, according to a report from the National Commission on Covid-19 and Criminal Justice (NCCCJ), continuing a multi-year downward trend.

According to the FBI’s preliminary 2020 findings, violent crime rose by 3% across the country last year. But the number of murders rose by 25% between 2019 and 2020 — the largest jump recorded in the US in a one-year period since the FBI began releasing annual figures in the 1960s. The NCCCJ’s findings were similar, citing a 30% increase in the homicide rate between 2019 and 2020 in the 34 major cities it surveyed.

Homicide can’t be treated like any other crime. Experts say that classifying an increase in homicides as part of a ‘crime wave’ obscures the fact that murder is a unique, devastating crime — one that requires targeted solutions.

“It wasn’t a surge in crime — it was a surge in murder. Murder is very specific, and if we’re going to have solutions we need to be specific about what the problem is,” said Jeff Asher, a crime analyst in New Orleans and the co-founder of the consulting company AH Datalytics.

The increase in homicide has continued into 2021. Asher has been tracking the number of homicides year-to-date across more than 70 major cities, and about two-thirds have had more homicides this year than the last.

Crime rates are not partisan. Asher’s data shows that murder appears to have risen uniformly across the country, contrary to partisan talking points that the increase is happening only in heavily Democratic areas.

“The political affiliation of the mayor of a city had nothing to do with the increase in homicide,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri St. Louis who co-authored the NCCCJ’s most recent report. “Cities with Republican mayors, cities with Democratic mayors, if they were reasonably large cities, they probably saw an increase.”

Gun violence is a driving factor.

We know that the rise in homicides is tied to increased gun violence in the past two years. According to the Gun Violence Archive, a non-profit organization that tracks gun-related violence in the United States, there were 39,538 gun deaths in 2019 compared to 43,559 in 2020. The bulk of that increase came from homicides or unintentional gun deaths, which rose by almost 4,000 between 2019 and 2020. Gun sales also soared during the pandemic.

Context is key. These numbers are no doubt alarming — but it’s important to put them in context with America’s history of lethal violence. The murder rate in 2020 was about 6.2 per 100,000 people, but that’s about 40% below what it was in the 1980s and 1990s, when homicides peaked in the United States.

That said, this downward trend is not consistent across the board. Last year, major cities like Philadelphia and St. Louis experienced their worst homicide numbers in decades, and Columbus saw the highest number of homicides ever recorded in the city when the murder rate jumped to 19 per 100,000 residents.

But experts urge caution when using a one-year increase to portend a longer-term trend. “A one-year homicide rate, even if it’s increased, should not be used to suggest we’re in the midst of a long-term uptick in homicide,” said Rosenfeld.

The Ferguson effect. In many cities, the jump in violent crime began shortly after the police killing of George Floyd in May, which led to social unrest and protests across the country. Rosenfeld, who has written about the “Ferguson effect,” examining the rise in homicides in 2015 following the police killing of Michael Brown, said that this year’s increase follows a similar pattern to what he’s previously observed.

“We see increases in homicide during periods of social unrest, but especially around police violence,” he said. “The increase, on average, was roughly twice the increase we saw five to six years ago, and that increase was quite sizable. But the difference between now and then is the pandemic.”

Eroding trust. The conversations surrounding policing last summer may have also exacerbated a decline in perceived police legitimacy. A Gallup poll from last summer found that confidence in the police had plummeted to an all-time low across the country.

Both researchers and former law enforcement officials told CNN that a loss of trust in law enforcement can have a domino effect, causing fewer victims of crime to seek help from the police, and reduce cooperation between law enforcement, those who have been arrested and even victims of crime.

What we don’t know

There’s a lot we don’t know yet about why homicides have risen, in large part because we simply don’t have the data.

Data reporting is voluntary. The most comprehensive source of nationwide data comes from the Federal Bureau of Investigations, which collects crime statistics from law enforcement agencies across the country through its Uniform Crime Reporting program. However, the program relies on agencies voluntarily collecting and reporting their crime data to the FBI — and less than 50% of agencies have done so this year.

There’s a long wait for numbers. There is also a significant delay between when data is released and the timeframe it covers: The FBI won’t release its full 2020 report until September of this year. While its preliminary report showed a 25% increase in homicides in 2020, several large cities did not submit data, including New York, Chicago and New Orleans. Compounding this problem is the FBI’s recently changed reporting system, which is more detailed but harder for agencies to compile, and may negatively impact the amount of data the agency releases this year.

We don’t track gun ownership or sales. While we know that US residents bought guns in record numbers last year, gun ownership data is incomplete at best. The FBI tracks pre-sale background checks, but there is no federal database of gun sales, and there’s no way to account for guns that may have been acquired illegally. Because of the inconsistent availability of data, it’s hard to know how closely a surge in gun purchases are tied to a rise in homicides.

While groups like the Gun Violence Archive, AH Datalytics and others have started compiling much of this information on their own, crime analysts say that federal data infrastructure must be improved in order to gain a better understanding of homicide.

“It shouldn’t be left to some professionals to put that data together,” John Roman, a senior fellow at NORC at the University of Chicago, told CNN. “We say all the time that violence is a public health problem, but we’ve never invested in data with crime (the way) that we do with public health.”

The pandemic eroded the social safety net. We likely won’t understand the impact that the pandemic has had on violent crime for several more years, but it’s important to keep the extraordinary circumstances of the past year in mind. Gun violence disproportionately affects lower-income communities of color, which have been hard-hit by Covid-19 and the job losses and lockdowns that resulted. Roman pointed to the effects of economic instability on young men in particular:

“If you’re between 18 and 30 and you’re a young man — and that’s who commits violence in America, by and large — those are all the routines of yours that were disrupted,” he said. “… And you’re staying home, you’ve had a ton of trauma in these areas and now there’s new trauma from the pandemic … that’s just a toxic recipe for violence.”

The role of police funding. Law enforcement officials across the country have pointed to the ‘defund the police’ movement, bail reform and a demoralized force as the drivers behind increased crime, but data suggests that it’s more complicated. The movement to reduce police budgets, for example, has struggled to gain traction across the country. A Bloomberg analysis based on reporting from the Associated Press found that of the 50 largest police agencies in the country, only four had cut their budgets for 2021 by more than 10%, and that many cities actually increased their police budgets for this year. Many of the cuts came amid larger, citywide budget reductions due to the pandemic.

It’s also not clear from available data that budget cuts are directly tied to higher crime rates. Despite an 11% police budget decrease, Seattle’s year-to-date homicides were down from 2020 at the end of May. Homicides are up this year in Austin, where the police budget was reduced by 30%, but murder rates have also increased in similarly sized cities like San Jose where the police did not face budget cuts.

What happens next?

The jump in homicide rates appears to be slowing in several major cities. During this year’s July 4 holiday weekend — typically a violent time for cities across America — there were 233 fatal shootings, down 26% from the year before. In Chicago, shootings year-to-date are flat between 2020 and 2021. In St. Louis, homicides year-to-date are down by 9%. We don’t know yet whether these trends will continue through the rest of 2021.

Experts warn that once the homicide rate starts to decline, it may do so slowly, as the economic and social fallout of 2020 will linger.

“The societal fabric has frayed, and it’s going to take a while to stitch it back together,” said Roman. “There’s a lot of new pain inflicted by 2020 and 2021, and it’s going to have to cycle its way out.”

The trauma that a rise in homicide can have on a community is far reaching and long lasting. As cities across the country grapple with the long-term impacts of gun violence, Shapiro says the media plays an important role in making sure these stories aren’t reduced just to statistics.

“Whether it’s the violence out of the barrel of a gun or the violence of police impunity, we need to understand that the story of a violent crime doesn’t begin the moment a trigger is pulled and doesn’t end the moment someone is arrested,” he said. “These traumas are going to play out over lives and years in important waves … we have a responsibility to tell the bigger story.”

As the United States grapples with an epidemic of gun violence and these reverberating impacts of homicide, it will take better research, consistent data collection and community-tailored approaches to understand and address the roots of violent crime. In the meantime, we can all benefit from a more critical, humane and nuanced understanding of how complicated crime data really is.

Related stories