Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Richard Branson have a combined net worth of $400 billion, roughly the size of the GDP of the entire nation of Ireland. And all three men have decided to put vast sums of their wealth into chasing their space travel dreams, creating a modern space race in which ultra-rich men — rather than countries — shoot for the stars.

The space companies founded by the three billionaires all have slightly different goals and varying visions of how to achieve them. But never has the Branson-Musk-Bezos dynamic appeared more competitive than when Branson announced earlier this month that he would fire himself into outer space on a suborbital joy ride just days before Bezos will clamber into his own rocket.

Branson’s flight took off without a hitch on Sunday, while Bezos plans to take off July 20.

But which billionaire is truly winning this so-called space race? It all depends on how you look at it.

Putting it in perspective

The press has billed Bezos, Branson and Musk as the three so-called space barons because of their similarities: All made their fortunes in other industries before setting their sites on extraterrestrial ventures — Musk in online payments and electric cars, Bezos with Amazon, and Branson with his empire of Virgin-branded businesses. And they all founded their companies within a few years of each other, becoming the most recognizable faces in the 21st-century space race, in which titans of private industry are racing each other to space, rather than Western governments racing Eastern governments like in the space race of last century.

But they certainly are not the only players in the game, and they may not be the only space barons for very long. There are hundreds of space startups across the United States and the world focused on everything from satellite tech to orbiting hotels. SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin have also all benefited greatly through partnerships with NASA and the US military, and all three continue to compete — and occasionally partner with — legacy aerospace companies, such as Boeing and Northrop Grumman and United Launch Alliance.

Elon Musk

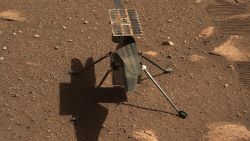

If there is a race underway, space fans are usually the first to declare SpaceX the frontrunner. Musk’s venture, founded in 2002, has built rockets capable of shuttling satellites and other cargo into Earth’s orbit, a trip that requires speeds topping 17,000 miles per hour, and built a 1,500-piece constellation of internet-beaming satellites; it’s figured out how to land and reuse much of its hardware after flight; and it’s won massive NASA and US military contracts.

It’s created and flown the most powerful rocket in operation — and performed synchronized landings of its boosters — and developed a spacecraft that successfully ferried astronauts to the International Space Station. Now SpaceX is working on creating a spaceship that will take humans to the moon and Mars.

Meanwhile, neither Branson’s nor Bezos’ companies have managed to take astronauts to orbit. Their companies have, relatively speaking, just scratched the edge of space.

Along the way, SpaceX collected a fervent base of supporters who defend his every move. But there’s no denying that SpaceX has frequently been the pioneer of the commercial space sector by breaking records, making history, and accomplishing things that industry professionals once deemed unfeasible. The company is credited with almost single-handedly disrupting the rocket industry, which was considered fairly stagnant and somewhat uninteresting for a couple of decades before SpaceX came along.

But on the other hand, Musk himself has not traveled to space, nor has he said when he would do so or if he is willing to take on the risk anytime soon. His most notable comment on the matter was that he’d “like to die on Mars, just not on impact.”

Musk, the world’s second richest man, has also criticized rivals for attempting to generate profits, as opposed to SpaceX, which has the stated goal of “making life multiplanetary.” Take that as you will.

Jeff Bezos

If one billionaire has made a desire not to rush-manufacture rockets a part of his brand, it’s Bezos. He founded Blue Origin in 2000 — six years after starting Amazon — and gave it the motto “gradatim ferociter,” a Latin phrase that translates to “step by step, ferociously.” The company’s mascot is also a tortoise, paying homage to the tortoise and the hare fable that made the “slow and steady wins the race” mantra a childhood staple.

“Our mascot is the tortoise because we believe slow is smooth and smooth is fast,” Bezos has said, which could be seen as an attempt to position Blue Origin as the anti-SpaceX, which is known to embrace speed and trial-and-error over slow, meticulous development processes.

For years, the company operated in almost complete secrecy. But now it’s goals are quite clear: Bezos, the world’s richest person, wants to eventually send people to live and work in spinning, orbital space coloniesto extend human life after Earth reaches a theoretical, far-off energy scarcity crisis. And he started Blue Origin in order to develop cheaper rocket and spacecraft technologies that would be necessary to creating such extraterrestrial housing. The company has also laid out plans for a lunar lander and to work alongside NASA and others to establish a moon base.

New Shepard — Blue Origin’s fully autonomous, reusable, suborbital rocket — was intended to be an early step toward creating lunar lander technology, helping to teach the company how to safely land a small spacecraft on the moon. But the company is also parlaying its New Shepard vehicle into a suborbital space tourism business in which it can sell tickets to wealthy thrill seekers — and that is at the core of the latest news cycle. Bezos and three others will be the first passengers ever to take the high-speed, 11-minute joyride aboard a New Shepard capsule.

And it also goes higher than Branson’s rocket, above the Kàrmàn Line at 100 kilometers (62 miles) altitude, the internationally-recognized border of space, as opposed to Branson’s spaceplane, which goes just over 50 miles up, which is what the US government recognizes as outer space.

But in the background, Blue Origin is still working on more ambitious technologies. It’s laid out plans for a gargantuan orbital rocket called New Glenn. It’s also selling the engines for its New Glenn rocket to legacy aerospace company United Launch Alliance, which is a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing. And it’s unveiled a concept for Blue Moon, its lunar lander.

SpaceX, however, has bested Blue Origin in competitions for several lucrative government contracts that help fund such projects,including a NASA lunar lander contract, which Blue Origin is currently contesting.

Separately, Amazon has also announced plans to create a constellation of internet-beaming satellites, much like SpaceX’s Starlink. Though Starlink is actually based on ideas that were first attempted in the 1990s, Musk has frequently accused Bezos of being a “copycat.”

Among the other incidents in which Bezos and Musk have sparred: Musk made a “blue balls” joke about Bezos’ “Blue Moon” spacecraft, a back-and-forth over who figured out how to land rocket boosters first, and a spat about whether Mars is a livable planet.

Richard Branson

Lately, however, Branson and Bezos’ rivalry has taken center stage.

Branson’s Virgin Galactic was founded with virtually the same business plan as Blue Origin’s with New Shepard: take paying customers on supersonic flights to the edge of space. Virgin Galactic’s technology looks far different — making use of a winged, rocket-powered spaceplane rather than a vertically launched rocket and capsule — but the short-term goal is practically identical.

Branson set off a wave of speculation that Virgin Galactic had rearranged its test flight plans in order to get Branson to space before Bezos’ flight on July 20.

Though Branson has long pledged to be the first space baron to actually travel to space, Virgin Galactic had encountered several major hurdles that have set its plans back by years. A tragic mishap during a 2014 test flight of the company’s SpaceShipTwo killed a co-pilot. And a series of other technical difficulties have had to be ironed out before the company was ready to deem the spacecraft safe enough to fly Branson.

Still, in the Branson vs. Bezos battle, Branson does have one bragging right that Bezos does not: Virgin Galactic has already made people into astronauts. Because the vehicle requires two pilots and has flown some Virgin Galactic employees as crew members on test flights, the company has already made astronauts out of eight people — including four pilots, Branson and a group of Virgin Galactic employees who flew as crew members — whereas every Blue Origin flight thus far has had nobody inside.

Not to mention, Branson has also sent a rocket to orbit. Again, that requires far more speed and rocket power than suborbital trips.

Branson’s Virgin Orbit, which spun off from Virgin Galactic in 2017, sent its first batch of satellites to orbit in January. Though Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne, which takes off from beneath the wing from a Boeing 747 jet, is not nearly as powerful as Musk’s Falcon 9s or Bezos’ planned New Glenn rockets, it is considered an industry leader in a niche race to develop rockets designed specifically for hauling small satellites, or smallsats, to space as they’ve boomed in popularity.

Virgin Galactic also has some bold long-term visions, including creating a suborbital, supersonic jet that can shuttle people between cities at breakneck speeds.

To sum it up: All three billionaires have similar but distinct extraterrestrial ambitions, and the goal is for the private sector to get satellites, people or cargo into space cheaper and quicker than has been possible in decades past. But the race — as much as it is one — can also be just as much about the eccentric personalities and egoism of some of the world’s richest men.