The devastating heat wave that ravaged British Columbia last week is being blamed for a massive die-off of mussels, clams and other marine animals that live on the beaches of Western Canada.

Christopher Harley, a professor in the zoology department at The University of British Columbia, found countless dead mussels popped open and rotting in their shells on Sunday at Kitsilano Beach, which is a few blocks away from his Vancouver home.

Harley studies the effects of climate change on the ecology of rocky shores where clams, mussels and sea stars live, so he wanted to see how the intertidal invertebrates were faring in the record heat wave that hit the area on June 26-28.

“I could smell that beach before I got to it, because there was already a lot of dead animals from the previous day, which was not the hottest of three,” he said. “I started having a look around just on my local beach and thought, ‘Oh, this, this can’t be good.’”

The next day, Harley and one of his students went to Lighthouse Park in West Vancouver, which he has been visiting for more than 12 years.

“It was a catastrophe over there,” he said. “There’s a really extensive mussel bed that coats the shore and most of those animals had died.”

Unprecedented heat

Mussels attach themselves to rocks and other surfaces and are used to being exposed to the air and sunlight during low tide, Harley said, but they generally can’t survive temperatures over 100 degrees for very long.

Temperatures in downtown Vancouver were 98.6 degrees on June 26, 99.5 on the 27th and 101.5 on the 28th.

It was even hotter on the beach.

Harley and his student used a FLIR thermal imaging camera that found surface temperatures topping 125 degrees.

At this time of the year, low tide hits at the hottest part of the day in the area, so the animals can’t make it until the tide comes back in, he said.

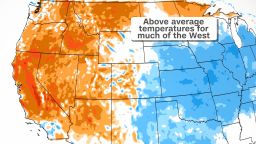

Climate scientists called the heat wave in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest in the United States “unprecedented” and warned that climate change would make these events more frequent and intense.

“We saw heat records over the weekend only to be broken again the next day,” Kristina Dahl, a senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told CNN, “particularly for a part of the country where this type of heat does not happen very often.”

An analysis by more than two dozen scientists at World Weather Attribution found that the heat wave “would have been virtually impossible without the influence of human-caused climate change.”

It was also incredibly dangerous.

Lytton, British Columbia, broke Canada’s all-time record on June 30 when the temperature topped 121 degrees. The town was all but destroyed in a deadly wildfire.

There were 719 deaths reported to the province’s coroners between June 25 and July 1 – three times as many as would normally occur during that time period, according to a statement from Lisa Lapointe, British Columbia’s chief coroner. Hundreds of people died in the US and many had to be hospitalized because of the heat.

A billion animals may have died

Harley said the heat may have killed as many as a billion mussels and other sea creatures in the Salish Sea, which includes the Strait of Georgia, the Puget Sound, and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, but he said that was a very preliminary estimate.

He said that 50 to 100 mussels could live in a spot the size of the palm of your hand and that several thousand could fit in an area the size of a kitchen stovetop.

“There’s 4,000-some miles of shoreline in the Salish Sea, so when you start to scale up from what we’re seeing locally to what we’re expecting, based on what we know where mussels live, you get to some very big numbers very quickly,” he said. “Then you start adding in all the other species, some of which are even more abundant.”

He said he’s worried that these sorts of events seem to be happening more often.

Brian Helmuth, a marine biology professor at Northeastern University, said that mussel beds, like coral reefs, serve as an early warning system for the health of the oceans.

“When we see mussel beds disappearing, they’re the main structuring species, so they’re almost like the trees in the forest that are providing a habitat for other species, so it’s really obvious when a mussel bed disappears,” he said. “When we start seeing die-offs of other smaller animals, because they’re moving around, because they’re not so dense, It’s not quite as obvious.”

He said the death of a mussel bed can cause “a cascading effect” on other species.

Both scientists said they were concerned that these heat waves were becoming more common and they weren’t sure whether the mussel beds would be able to recover.

“What worries me is that if you start getting heat waves like this, every 10 years instead of every 1,000 years or every five years, then it’s – myou’re getting hit too hard, too rapidly to actually ever recover,” Harley said. “And then the ecosystem is going to just look very, very different.”