Richard Branson will take a rocket-powered space plane on a 2,400 mile-per-hour ride to the edge of space this weekend. That’s if everything goes according to plan. And there’s plenty that could go wrong.

The rocket motor could fail to light up. The cabin could lose pressure and threaten the passengers’ lives. And the intense physics involved when hurtling out of — and back into — the Earth’s atmosphere could tear the vehicle apart.

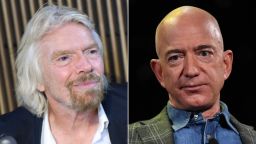

And now Branson is ready to follow in the footsteps of the test pilots and Virgin Galactic employees who have already flown on VSS Unity, the vehicle Branson’s company, Virgin Galactic, has spent nearly two decades working to develop. If all goes as planned, Branson will also be the first billionaire ever to travel to space aboard a vehicle he helped fund the development of, beating fellow space baron Jeff Bezos by just nine days.

Still, Virgin Galactic has built safety backstops into its spaceplane, completed more than 20 test flights, three of which have successfully reached the edge of space, received the go-ahead from an internal safety review board and a green light from federal regulators to host passengers.

Any time humans are on an airborne vehicle, there’s risk involved. Here’s a breakdown of just how much danger Branson -— and the three people going with him — will be taking on.

About the space plane: VSS Unity

Richard Branson founded Virgin Galactic in 2004, after watching a space plane called SpaceShipOne rocket into space to win the Ansari X Prize. Branson bought the rights to that tech, and a team of engineers set to work developing a larger vehicle capable of carrying two pilots and up to six paying customers on a high-speed joy rides. The evolved designed is called SpaceShipTwo.

SpaceShipTwo takes off from an airplane runway attached beneath the wing of a massive, custom-designed quad-jet double-fuselage mothership known as WhiteKnightTwo. Once the mothership reaches about 40,000 feet, the rocket-powered plane is dropped from in between WhiteKnightTwo’s twin fuselages, and fires up its engine to swoop directly upward, accelerating up to more than three times the speed of sound, or 2,300 miles an hour.

Once it reaches the very top of its flight path, it hangs, suspended in microgravity, as it flips onto its belly before gliding back down to a runway landing. From takeoff to landing, the whole trip takes roughly an hour.

VSS Unity — the name of the SpaceShipTwo that Branson will be taking to space and the first to make the full trek — has completed three successful test flights that’ve reached space. But the company’s development program has also endured years of delays for a variety of reasons, including a fatal 2014 crash that killed a test pilot.

A planned test flight in December was also halted when VSS Unity’s onboard rocket motor computer lost connection. And Virgin Galactic encountered a potentially serious safety hazard during a test flight in 2019, New Yorker staff writer Nicholas Schmidle revealed in a new book, “Test Gods.” A safety probe was ordered to investigate why a seal on its space plane’s wing had come undone, risking loss of the vehicle and the lives of the three crew members on board. No one was harmed in the test flight, which was publicly deemed a success.

But after VSS Unity’s third test flight in May, the company received approval from the Federal Aviation Administration to begin flying passengers. That doesn’t mean, however, that the FAA — which is focused primarily on ensuring safety of people and property on the ground — is guaranteeing the spacecraft is safe. That decision is left up to Virgin Galactic, and the company made the surprise announcement on July 1 that Branson would be on the very next test flight — becoming the first non-crew member ever to make the trek — this Sunday.

Markus Guerster, an aerospace industry professional who co-authored a 2018 paper on the risks of suborbital space tourism, said there is never a perfect time for a company to deem its spacecraft safe enough to fly members of the public.

“It’s kind of a difficult decision to make — if you’re ready, or if you’re not ready, because there is some risk remaining. But if you don’t try it, you’re also not going to learn,” Guerster said. “I think the first group of people who will fly on this acknowledge the risk. There are plenty people out there who climb Mount Everest.”

Orbital vs. Suborbital flights

When most people think about spaceflight, they think about an astronaut circling the Earth, floating in space, for at least a few days.

That is not what Branson — or Bezos, for that matter — will be doing.

They’ll be going up and coming right back down. Virgin Galactic’s flights are brief, up-and-down trips, though they will go more than 50 miles above Earth, which the United States government considers to mark the boundary of outer space.

Virgin Galactic’s suborbital flights hit about more than three times the speed of sound — roughly 2,300 miles per hour — and fly directly upward. The plane will hover at the top of its flight path, giving passengers a few minutes of weightlessness. It works sort of like an extended version of the weightlessness you experience when you reach the peak of a roller coaster hill, just before gravity brings your cart — or, in Branson’s case, your space plane -— screaming back down toward the ground.

VSS Unity will then deploy what’s called a “feathering system,” which allows the space plane’s wings to fold up, mimicking the shape of a badminton shuttlecock so it can reorient itself as it begins its descent. It then unfurls its wings again and glides back down to a runway landing.

But it hasn’t always worked well. The feathering system was determined to be the “probable cause” of Virgin Galactic’s fatal 2014 test flight incident, which took the life of the co-pilot, Michael Alsbury, and left the pilot badly injured. The feathering system was deployed prematurely due to human error, causing the vehicle to rip apart mid air. The company has since parted ways with its manufacturing partner and installed a computerized safe guard to prevent the same mistake from occurring again.

New Shepard vs. SpaceShipTwo

Though Branson has denied that his attempt to reach space this weekend has anything to do with the timing of Bezos’ flight, it’s sparked plenty of talk about a billionaire space race. And, when it comes to risk, Guerster said there are plenty of pros and cons about the vehicles Branson and Bezos will be taking.

Virgin Galactic’s space plane has some inherent advantages: The fact that VSS Unity has wings and takes off horizontally from a runway give the pilots more time to correct course if something goes wrong. With the New Shepard’s rocket-and-capsule system Bezos will be flying on, there’s slimmer room for error, according to Guerster. Though, New Shepard does have an emergency escape system in place that can eject passengers away from a malfunctioning rocket, and jettison them to a parachute landing if necessary.

The other major difference between the spacecraft is that VSS Unity requires two pilots to fly, while New Shepard is fully automated. Experts are split when it comes to assessing those different approaches.

“You can’t really say what is better what is worse,” Guerster said.

Still, New Shepard has also flown 15 different test missions and never had a catastrophic accident. And that’s why Guerster said that — if he had to choose which spacecraft he’d strap himself into first — he’d chose Bezos’ New Shepard.

But then, Guerster added, he’d also be willing to take a trip on Virgin Galactic’s VSS Unity.

“I think it’s a more exciting ride,” he said.