In Mongolia, hospitals are overwhelmed. In the tiny archipelago of Seychelles, more than 100 new Covid-19 cases are being reported each day. And in Chile, a nationwide lockdown was lifted this week – but the country is still reporting thousands of daily cases.

What links these countries is that they have each fully inoculated more than 50% of their populations, largely with Chinese-made coronavirus vaccines. And that’s raised questions over the vaccines’ efficacy.

If the Chinese vaccines aren’t working, that’s a huge problem – and not just from a health perspective. Beijing has staked its reputation on providing other countries with vaccines.

As Western nations stockpiled supplies for their own populations, China sent vaccines overseas – in June, the foreign ministry announced the country had delivered more than 350 million Covid-19 vaccine doses to more than 80 countries. That mission highlighted inadequate Western efforts at a time when tensions between China and many major democracies were running high.

Questions over the efficacy of China’s Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines now jeopardize that soft-power win for Beijing, although China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin has dismissed such criticism as a “bias-motivated … smear.”

Experts say that while these Chinese vaccines might not be as effective as some, they aren’t a failure. No vaccine gives 100% protection against Covid-19, so breakthrough cases are to be expected.

The crucial metric for measuring success, they say, is preventing deaths and hospitalizations, not aiming for zero Covid-19.

Why are vaccinated people getting sick?

China has two vaccines authorized for emergency use by the World Health Organization (WHO), Sinopharm and Sinovac. Both use inactivated viruses to prompt an immune response in the patient, a tried and tested vaccine method.

Pfizer and Moderna, by contrast, use a newer technology called mRNA, which teaches the body’s cells how to make a piece of the coronavirus spike protein that triggers an immune response.

So far, trials show Sinopharm and Sinovac have a lower efficacy against Covid-19 than their mRNA counterparts. In Brazilian trials, Sinovac had about 50% efficacy against symptomatic Covid-19, and 100% effectiveness against severe disease, according to trial data submitted to the WHO. Sinopharm’s efficacy for both symptomatic and hospitalized disease was estimated at 79%, according to the WHO.

Both Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Covid-19 are more than 90% effective against symptomatic Covid-19. Global efficacy studies of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine showed it was 66% effective against moderate to severe illness, 85% effective against severe disease and 100% effective at preventing death. The trials took place at different times, and in places where different variants were circulating.

Experts say the outbreaks in places that used Chinese vaccines are broadly in line with what we would expect from these efficacy rates.

“If we want to bring down the severe cases (and) the number of deaths, the Sinopharm, Sinovac can help,” said Jin Dong-yan, a professor in molecular virology at Hong Kong University.

Ben Cowling, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the same university, said the Chinese vaccines appeared to be limiting the number of serious infections and deaths.

“I think the vaccines are certainly working and they’re certainly saving a lot of lives,” he said.

What’s going on in Chile, Mongolia and Seychelles?

Chile is reporting thousands of new Covid-19 cases each day. There, 55% of the population is fully vaccinated, and among that cohort almost 80% received Sinovac.

But according to the Ministry of Health, 73% of cases in the intensive care unit between June 17 and 23 were not fully vaccinated.

It’s a similar situation in the Seychelles, where authorities said almost all critical and severe cases of Covid-19 were in people who had not been fully vaccinated. The country is using Sinopharm in adults under 60, while over 60s get Covishield, the AstraZeneca vaccine made in India, which has a similar efficacy rate of 76% against symptomatic Covid-19 and 100% efficacy against severe or critical Covid-19.

The Seychelles Ministry of Health said in a Facebook post last month that of the 63 people who had died from Covid-19 in the country at the time, three had been vaccinated with two doses. All three were aged between 51 and 80. CNN has reached out to the Ministry of Health for comment.

Mongolia has fully vaccinated 53% of its population, with 80% of those people receiving Sinopharm, according to Enkhsaihan Lkhagvasuren, the Ministry of Health’s head of public health policy implementation. A fifth of Mongolia’s Covid-19 cases have been fully vaccinated, but 96% of Covid-19 deaths were in people who were either unvaccinated or had received just one dose, Lkhagvasuren said.

To reach herd immunity, Lkhagvasuren said more than 80% of the population needed to be inoculated. The country of 3 million still has 1.6 million people vulnerable to Covid-19, she said.

And she maintained that Sinopharm had been very effective.

“We cannot differentiate between Covid-19 vaccines, saying this one is bad or that one is good. All of the available vaccines reduce the risk of severe illness,” she said.

Odgerel Chuluunbat, a fully vaccinated business owner in Mongolia’s capital Ulaanbaatar who tested positive for Covid-19 two weeks ago and recovered at home, said she believed her infection could have been much worse without the Sinopharm vaccine.

“I don’t regret getting the jab,” she said. “Without it, the situation in the country would be very bad.”

With global vaccines in short supply, many developing countries had few other options. Mongolia was allocated more than 112,000 AstraZeneca doses and 126,000 Pfizer doses via COVAX, but production issues and India’s outbreak have delayed deliveries.

Why are vaccinated people dying?

Some people who are getting vaccinated with Sinovac or Sinopharm are still dying of Covid – although these breakthrough cases are possible with any vaccine.

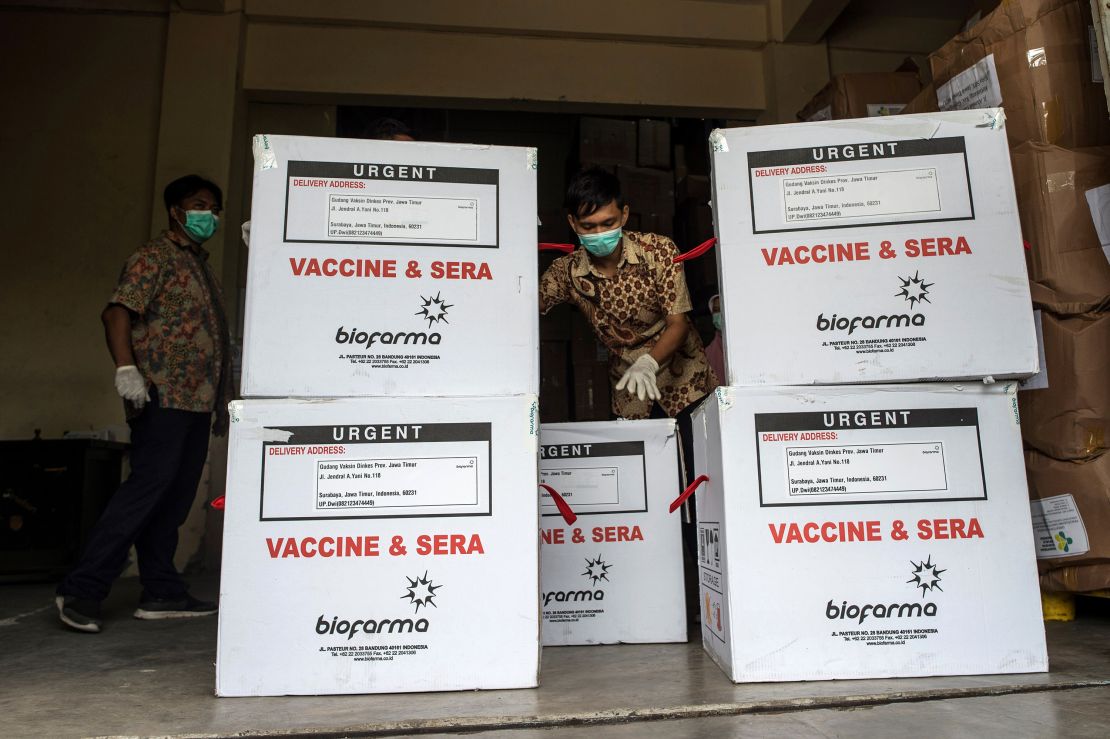

In Indonesia, which the Red Cross warned this week is “on the edge of catastrophe,” at least 88 doctors died of Covid-19 between February and June 26. At least 20 were fully vaccinated with Sinovac, according to Dr. Adib Khumaidi, the chief of Indonesian Medical Association’s risk mitigation team. Another 35 had not been vaccinated, and 33 deaths are still under investigation.

An estimated 1,600 doctors in Indonesia have been infected with Covid-19 in May and June alone, although it’s unclear how many of those had been vaccinated.

Adib said most medical workers died because they were in a unique circumstance: they were overwhelmed with patients, meaning they had to work long hours with little rest.

“Based on our investigation data, the death of medical workers has nothing to do with the Sinovac vaccine,” Adib said. “The most important thing is taking the Covid vaccine and people should keep following health protocols.”

Dr. Hermawan Saputra, an epidemiologist and member of the Indonesian Public Health Experts Association, said more virulent strains of Covid-19 may have reduced the efficacy of the vaccines.

The issue of inoculated people dying from Covid-19 is not contained to Chinese vaccines. A Public Health England report in June found that of the 117 people who died within 28 days of testing positive for the Delta variant in the UK, 50 had received two doses. But such deaths are rare – in total, there were 92,029 Delta cases, of which 58% were unvaccinated. The UK is using Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech, which are both mRNA vaccines, and Oxford/AstraZeneca, which uses a different technology.

In an article in the Guardian, statisticians David Spiegelhalter and Anthony Masters said some deaths were to be expected from good, but not perfect, vaccines.

Virologist Jin cautioned there could be underlying issues in these serious cases. Some vaccinated people hospitalized with Covid-19 might be immunocompromized, meaning their body is not able to produce a strong immune response, he said.

Have the Chinese vaccines failed?

Pfizer and Moderna vaccines appear to be more effective than Sinovac and Sinopharm at limiting transmission, but whether the two WHO-approved Chinese vaccines have failed depends on the metrics for success.

Jin said the Chinese vaccines’ efficacy might not be high enough to stop the virus circulating in a community, thereby putting herd immunity out of reach. That runs the risk of vaccine-resistant variants emerging.

“It’s possible that the end of the pandemic might be delayed, or we might have to work with these flu-like diseases for a longer period of time,” Jin said. “(The Sinovac, Sinopharm vaccines) are good, but they’re just not good enough. We want the vaccine to help put an end to the pandemic, and if that is the case, Pfizer and Moderna are doing a much better job.”

He said the manufacturers of the Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines have a responsibility to improve, which could just be a matter of increasing the dose or adding a third dose.

There are also signs China might not rely entirely on homegrown vaccines in the future. China’s Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical said in a Hong Kong Stock Exchange filing that it would work with BioNTech to produce up to 1 billion vaccines annually.

Pfizer and Moderna may roll out in more countries next year after manufacturing capacity is increased. But right now, there’s just not enough to go around.

Even so, getting a Chinese vaccine is still better than nothing, said Scott Rosenstein, director of the global health program at Eurasia Group.

“In places where that’s the only option, it still remains the best decision to take it,” he said.

And he worries that criticism of the Chinese vaccines may encourage people to wait until more effective vaccines become available.

“That itself creates challenges for the rollout, it means that you vaccinate people slower,” he said.

How does politics play into this?

As it exports vaccines around the world, Beijing has promoted the Sinopharm and Sinovac shots as “Chinese vaccines,” aligning the products with China’s government in a way not seen in the US or the UK.

After the WHO validated Sinovac and more efficacy data on Sinopharm was released in June, for example, state media Xinhua ran an editorial under the headline: “Latest evidence reaffirms Chinese vaccines’ benefits to the world.”

When the vaccines are a success, that reflects well on the Chinese Communist Party, even though Sinovac is a privately owned company (Sinopharm is state-owned). But because China’s shots are often flattened to “Chinese vaccines,” when there are questions over efficacy, that impacts all of them – and hurts the party, too.

Neither vaccine company has made extensive trial data public, which may allow efficacy questions to continue.

“The most I can say about that data is that those vaccines seem to work OK,” Rosenstein said. “You’re sort of partially flying blind here because the gold standard is a randomized trial, and we don’t have that much to work with for those.”

The lack of data has fed skepticism. Now reports of cases even among vaccinated people is prompting a backlash. In Mongolia, where there’s already a long-running anti-China sentiment, partly thanks to a belief that neighboring China wants to undermine its sovereignty, many are frustrated about the rate of infections.

Gandi Boldbaatar, a 22-year-old student, said she was fully vaccinated with Sinopharm a month ago, but tested positive for Covid-19 last week and is now in intensive care in a government hospital. She said she didn’t think Mongolia’s vaccination campaign was very effective.

“I still got very sick,” she said. “If given the option to get inoculated again with Sinopharm or any other vaccine, I will refuse it.”

Some of the backlash is wrapped up in “political scorekeeping” over the vaccines, said Rosenstein. When China’s efforts started, Western countries were accused of hoarding vaccines. Questions over Chinese vaccine efficacy have come about as the US announced its own plans to donate millions of vaccines abroad.

“It’s too early to say that the verdict is in,” Rosenstein said. “The downside (of vaccine diplomacy) may have outweighed the upside … I think that the vaccine diplomacy objectives of China at this point are not being realized.”

But the bigger picture, Rosenstein said, isn’t about politics – it’s about health.

“It’s bad for public health when you have so much political jockeying instead of good faith discussions around what’s the best way to get this outbreak under control.”

Julia Hollingsworth wrote and reported from Hong Kong, with reporting from Saruul Enkhbold in Ulaanbaatar, Amy Sood and Sophie Jeong in Hong Kong, Yong Xiong in Seoul, Angus Watson in Sydney, David Culver in Beijing and Cristopher Ulloa in Santiago.