Editor’s Note: Karlos K. Hill is associate professor and chair of the Clara Luper Department of African and Africana Studies at the University of Oklahoma and the author of “The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History.” The views expressed here are his own. Watch CNN Films’ “Dreamland: The Burning of Black Wall Street” Saturday, June 5 at 9 p.m ET, and read more opinion on CNN.

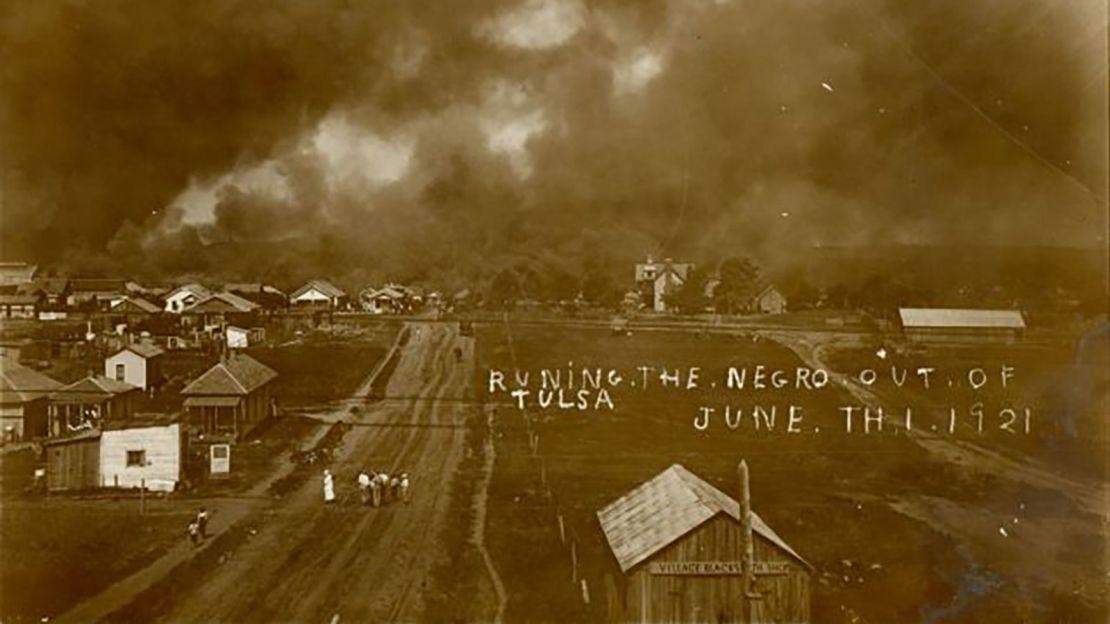

Over the course of May 31 and June 1 in 1921, a White mob numbering in the thousands carried out an armed assault on the Black community of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, attacking and killing Black residents and burning businesses, schools, churches, hospitals and homes. Firefighters were prevented from extinguishing the flames, which eventually consumed the Greenwood District, destroying an area comprising 35 city blocks.

The solemnity that naturally accompanies such an occasion as the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre will be tinged with special poignancy in this case: Among those observing the centennial will be three people who lived through the violence. Viola Fletcher, who is 107 years old; Lessie Bennington Randle, who is 106; and Hugh Van Ellis, who is 100. The fact that there are living survivors adds a new layer of meaning to this anniversary. It is crucial that we use the occasion to center their voices, their experiences and their calls for justice.

Testifying before the House Judiciary Committee earlier this month, Fletcher spoke searing words: “I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street. I still smell smoke and see fire,” Fletcher testified. “I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. I have lived through the massacre every day.”

If the 100th anniversary commemoration is to be meaningful, we must pay tribute to those who died, in memory of their sacrifice, and honor those who survived, for their resilience in response to what they had to endure. At minimum, honoring their sacrifice must include identifying and reinterring any victims who now lie in unmarked graves, along with providing restitution and support for the remaining survivors.

In 1921, the city of Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma failed to deliver justice to the victims and survivors of America’s worst race massacre. This occasion offers another opportunity to restore what the remaining survivors and the members of the Greenwood community deserve: justice.

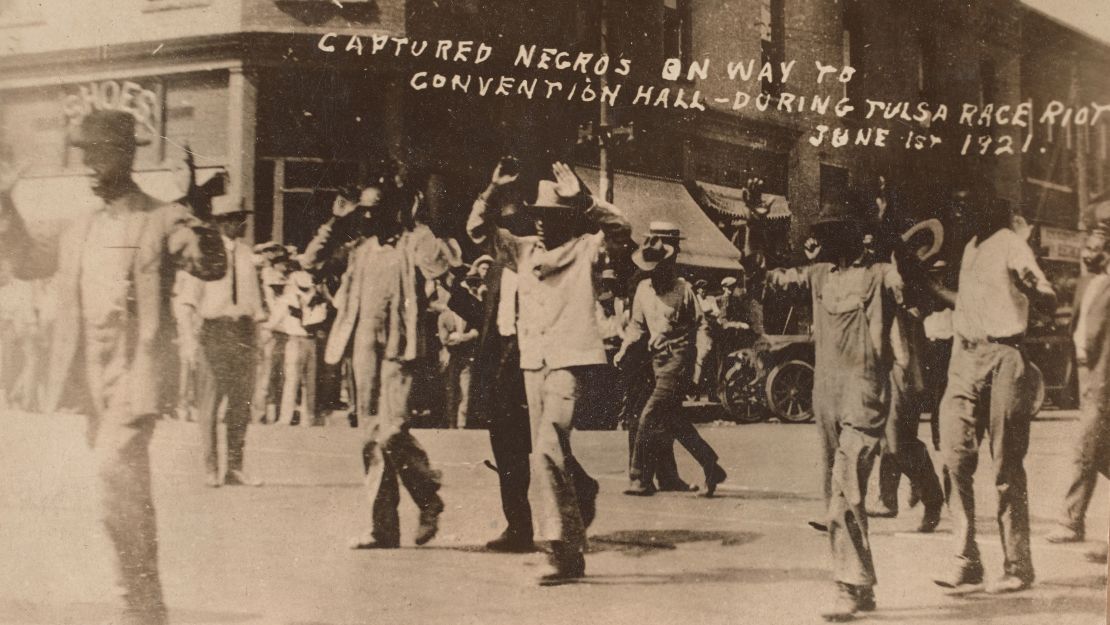

I am not an Oklahoma native. I moved here five years ago to teach Black Studies at the University of Oklahoma. Like so many others, I have struggled to comprehend how an area the size of Greenwood, with its deep community roots, could be destroyed so quickly and so thoroughly. I looked at the numerous photos that White participants and spectators took as Greenwood burned, and while they helped me as a historian to understand the scope and scale of the chaos, death, and destruction, I could not fully grasp such an inconceivable assault on a civilian community. It took guidance from the Greenwood community – the stories of survivors and descendants, the elders who have made it a point to actively remember this history that Tulsa wanted them to forget, and the current residents who care deeply that the victims and survivors are honored – to move me toward the understanding that I now have of the massacre.

Before it happened, over 11,000 Black residents called Greenwood home, and nearly 200 Black-owned businesses in the district were proof that even at the height of the Jim Crow era, Black entrepreneurs could not only survive but thrive. The value of Greenwood residents’ landholdings circa 1921 has been estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars today. Black leaders across the United States, including Booker T. Washington, pointed to Greenwood’s “Black Wall Street” as an example of how Black community commitment could foster a thriving Black urban economy.

In my recently published book, “The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History,” I grapple with the photographic legacy of this tragic history. The book was born out of the recognition that for decades following the massacre photos of what occurred were either hidden from public view or destroyed. The photos leave no doubt that what occurred on May 31 and June 1, 1921 was indeed a massacre, as those who lived through it insisted from the outset. With only three of those people still alive, it is more important than ever to center the survivor experience in the telling of what occurred.

As was so often the case with extrajudicial violence under Jim Crow, a rumor (subsequently debunked) that a Black man had attacked a White girl precipitated the torrent of violence and destruction. By the time it was all over – ended only by the governor’s imposition of martial law on the morning of June 1 – more than 300 people (mostly Black) had been killed, and countless more were wounded. Hundreds of homes had been destroyed, and Greenwood’s thriving business district, a shining example of Black entrepreneurial spirit in America, had been reduced to ashes.

While the scope of the attack in 1921 was unprecedented, remembering Tulsa 100 years on also means reckoning with the knowledge that White mob violence was a common experience for Black Oklahomans. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries (especially between the years 1907 and 1950), nearly 80 Black people were lynched in the state. During the two decades leading up to the massacre, White mobs had attacked, burned and looted six Black communities in Oklahoma, most notably in Dewey, where some 20 families lost their homes in 1918 when a White mob set fire to the Black section of town.

Although the events in Greenwood as described by the Black survivors clearly met the definition of a massacre, Tulsa-area newspapers and city leaders were quick to reframe the violence as having been initiated by Blacks in rebellion against White Tulsans. For decades that perspective prevailed in the White media and in history books, if they mentioned the violence in Greenwood at all. By perpetuating the “negro uprising” narrative, the city and local insurance companies were able to avoid making payments to deserving Black homeowners and Black business owners who had lost everything. Fixing blame on the Black community, not the White perpetrators, benefited White power.

Although Black Tulsans rebuilt homes and businesses, Greenwood has never fully recovered from the devastation of those two days in 1921. This is surely what the White mob hoped would happen as they murdered and burned their way through so many blocks of successful businesses, vibrant churches and beautiful family homes.

There has always been a racial wealth gap in the city, but it currently seems to be widening. There are now, in fact, “two Tulsas.” In North Tulsa, which is largely Black, 35% of residents live below the federal poverty line. The area is a food desert, and its schools are failing. Young Black entrepreneurs are hampered by racial inequality and a lack of opportunities.

South Tulsa, in contrast, is more affluent, and its residents are largely White. Whereas more than one-third of North Tulsans live in poverty, only 13 percent of South Tulsa residents live in poverty. According to Census figures, the median yearly household income for North Tulsa is $28,867. By contrast, South Tulsa’s median yearly household income is almost double, at $59,908.

One hundred years after this deadly attack, the Greenwood community is still picking up the pieces. In October 2020, an archaeological team discovered a large grave shaft containing 12 coffins. Further examination is needed, but it should be noted that it was found at a site where survivors claimed that Whites disposed of the remains of Black massacre victims in unmarked graves. Greenwood residents have long been traumatized by the thought that they might unknowingly be walking atop the bodies of family members and loved ones. The current effort to identify massacre victims will hopefully afford them some measure of closure as well as enable identified victims to receive the proper burial they have always deserved.

For nearly 100 years Black survivors and their descendants have fought to be compensated for the lives and property lost during the massacre. And for nearly 100 years their demands have gone unheard. The three remaining survivors are currently involved in a historic restitution lawsuit against the City of Tulsa and the State of Oklahoma.

Victory will be an uphill climb: Despite characterizing Tulsa and the site of the ongoing investigation into mass burials as a crime scene, even the mayor of Tulsa has opposed financial restitution for survivors, asserting that reparations will only divide on an issue Tulsans should be unified around. In 1921 and 2003, similar lawsuits were dismissed by Oklahoma courts. We must demand a different outcome this time.