The title to the classic 1970s hit “It Never Rains in Southern California” has nothing to do with climate change or even precipitation for that matter, but it couldn’t be more appropriate for the massive drought hitting the entire state this spring.

All of California is in drought, ranging from moderate (level D1) to exceptional (level D4). The last time this happened was in October 2014.

The drought has intensified, with the worst level now covering 14% of the state, up from 5% last week.

“Moving into dry season, California is expecting drought impacts to intensify during the summer months,” this week’s US Drought Monitor summaryexplains.

The winter rain and snow were again well below average and the long-term water deficit over the West is creating the potential for another devastating wildfire season.

“There’s no sugar coating it. It looks like fire season 2021 is going to be a rough one in California, and throughout much of the West, unfortunately,” warns Daniel Swain, climate scientist for UCLA and The Nature Conservancy.

“A combination of factors – including short-term severe to extreme drought and long-term climate change – are in alignment for yet another year of exceptionally high risk across much of California’s potentially flammable landscapes,” Swain says.

Fire has now become a way of life in the Western states, just like severe weather is in the Plains. It is no longer if it occurs, but when, where and how bad.

The 2020 fire season was the worst in the state’s history and 2021 could potentially be worse.

As of May 5, California has already seen seven times the amount of acres burned, compared to the same time frame last year.

Gov. Gavin Newsom this week issued an emergency declaration for much of the state to deal with the drought crisis.

The declaration directs state agencies to take action to increase drought resilience, modify reservoir releases to conserve water, and allows for more flexible water transfers between rights holders.

Swain explains why this year’s fire season is so concerning:

Some aspects of fire season are predictable, such as the state of the vegetation leading into it and temperature projections for the summer to come. Both of those point in the direction of an elevated risk.

Since vegetation conditions are currently setting new records for dryness and flammability, and because the seasonal outlook continues to call for a warmer than average summer/autumn across most of California, it’s easy to see why many folks are concerned.

“Each year is unique. Drought helps set the stage,” says Amanda Sheffield with the federal National Integrated Drought Information System.

Not enough snow to provide adequate water

“California and many parts of the West rely on snowpack for water resources. The poor snowpack, plus rapid spring snow melt has left areas of the West with not just low snow water equivalent (SWE) compared to normal for this date, but almost no SWE at all, including California at just 6% of normal and the Lower Colorado at just 4% of normal,” says Sheffield, the California-Nevada regional drought information coordinator with the agency.

“There’s essentially no snowpack left in the mountains,” confirms Swain. “What’s amazing to me as a climate scientist is to see the snow melt occur and then to see the rivers lakes and steams not responding. The soil under the snow is so dry that there is no runoff.”

“This is one of the reasons why I think the highest increase in risk for wildfires will probably be in the forests. The risk of big true forest fires is going to be especially elevated in California,” says Swain. He predicts the Sierra Nevada, the foothills ringing the Central Valley and the coastal forests including the redwoods are very much at risk.

Other states in the West also are dealing with extreme water shortages.

The snowpack in all of the states west of the Continental Divide is below normal and early-season warm weather is melting much of what’s there.

“Severe and still-worsening drought, extremely dry vegetation, plus strong expectation of a hotter-than-average summer are deeply concerning,” says Swain.

The record 2020 wildfire season was not all human-induced. Millions of acres burned due to lightning strikes alone.

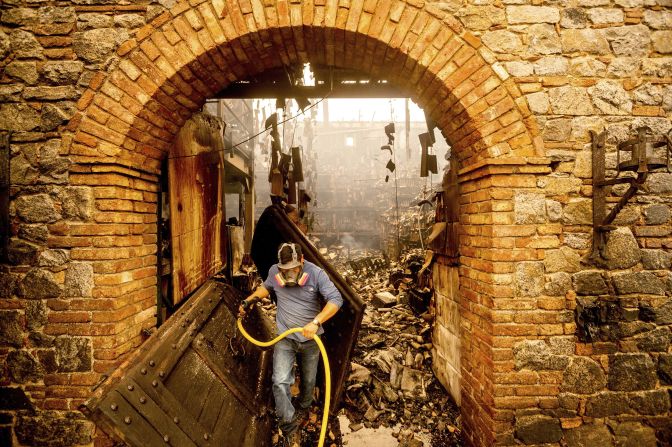

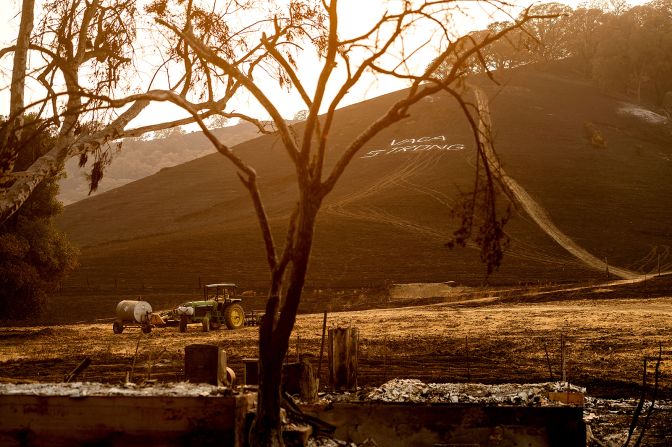

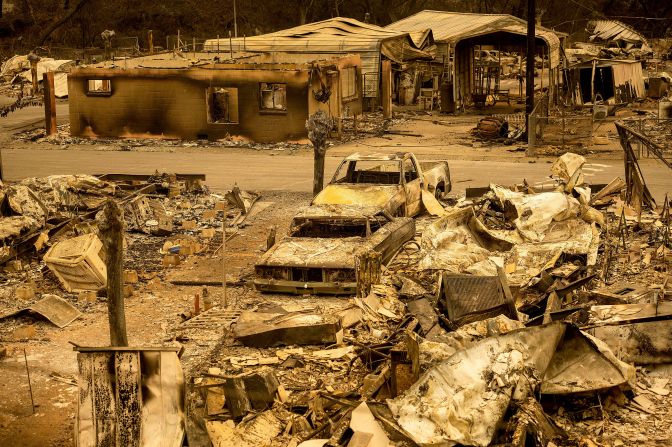

In photos: 2020 wildfires on the West Coast

“Pretty much everything that happened between August and September (2020) was lightning activity throughout the state,” says Isaac Sanchez, Cal Fire battalion chief of communications. “It was an unprecedented event that lead to a thousand, if not more, fire ignitions.”

The SCU Lightning Complex, LNU Lightning Complex and North Complex fires – all ignited by lighting – consumed over a million acres last year. Affected counties included Santa Clara, Alameda, Contra Costa, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Napa, Sonoma, Lake, Yolo, Solano, Plumas , Butte and Yuba.

Lightning-induced fires typically start in remote and hard-to-fight areas in the Sierras, but often are blown by wind into cities and towns in the fire’s path.

Firefighting assets may be stretched

With all of California in some level of drought, lightning again may contribute a significant percentage of burned acreage in 2021.

“I wish there was one item that we could point to and say, here it is, if we could just fix this one thing, everything would be better. But it’s a combination of things,” says Sanchez. “Primarily, what we are seeing is the increased window in which a destructive wildfire will burn. It’s starting earlier in the year and lasting deeper into the year.”

“The results are drier conditions sooner than we’ve ever had them before, which once a spark is introduced into the environment, it’s just a hop, skip and a jump before it turns into a large destructive fire.” Sanchez adds.

Firefighting efforts in the West often rely on mutual aid. Assets are moved from one area not experiencing fire to other areas that are. That concentrated effort may be in jeopardy this year with widespread fires occurring in many states.

“Everything from the Rocky Mountain continental divide westward, including Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico have fire conditions that look really, potentially explosive. The drought is even worse in those places than in California,” says Swain. “It looks pretty likely that it will be a severe fire season across most of the West.”