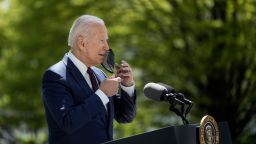

When President Joe Biden delivers his first address to Congress on Wednesday, two of the past year’s ground-shaking events will be hard to ignore.

The room where he’ll deliver it is exactly where a riot of would-be insurrectionists tried to prevent him from becoming president. And for the first time in history, a pair of women will be seated on the rostrum – and both will be wearing face masks. When the President enters the House chamber to the shouted introduction from the House Sergeant at Arms, he will also be wearing a mask before removing it to speak.

Biden plans to reference both the January 6 riot and the historic tableau behind him during his remarks, according to people familiar with his speech preparations, a nod to the weighty environment in which he will make the highly symbolic yearly address for the first time. Before he speaks, he’ll meet with Capitol staff who weathered the insurrection attempt.

Biden has been working with his speechwriters and senior aides for weeks on remarks that will both acknowledge the unusual circumstances of his address – only 200 people will be allowed in the room, compared to a normal crowd of more than 1,000 – while still capturing the sweeping agenda he has sought to enact over his first 100 days in office.

The biggest challenge facing Biden and his speechwriters in the final days before his remarks was paring down the address, one official told CNN.

The ongoing pandemic, impossible to ignore in the drastically altered setting, will constitute a major portion of Biden’s speech, officials say. His principal 100 day milestone, getting 200 million vaccine shots in American arms, has been achieved. And on Tuesday he announced an easing of mask guidelines after saying he would ask Americans to wear them for 100 days.

The heart of Biden’s speech is expected to be a formal unveiling of the second part of his jobs and infrastructure plan, which includes new spending on child care, family leave and education paid for by a tax hike on the wealthy.

People familiar with the speech describe a unifying message akin to Biden’s promises at the outset of his presidency to bring the country together – a message likely to cause scoffs among Republicans, who have felt left out after Biden pushed through his initial legislative agenda without them.

Meticulously planned and rehearsed

A highly engaged writer, Biden has spent hours debating the language and themes of his speech with his team, according to people familiar with his preparation. He has also consulted with members of his family. He has reviewed drafts and sent back handwritten revisions in the margins, along with dictating portions of his speech during writing sessions in the White House residence and Oval Office – and during quiet reflection back home in Delaware, where aides say he is at once relaxed and focused.

As president, Biden has prepared extensively for some of his most high-profile events, including a prime-time address to the nation in March and a solo press conference a few weeks later. For that address, Biden spent days line editing his remarks, ensuring he was striking the appropriate tone while using exactly the right words and phrases. Biden did not want to make a single mistake, he told officials. Ahead of the news conference he held an informal mock session with his team.

Biden is known to rehearse his major speeches repeatedly and will spend most of Wednesday preparing for this address. At some point before Wednesday’s 9 p.m. ET remarks, he is expected to stage a full run-through at the White House. Previous presidents have set up a podium and teleprompter in the White House Map Room to get as thorough a feel for the speech as possible.

Unlike any of his most recent predecessors, however, Biden will know what the view from the microphone will look like. He spent eight years looking out at the House Chamber – and the back of President Barack Obama’s head – during State of the Union speeches. For three-and-a-half decades before that, Biden was among the crowd of lawmakers watching from the floor.

Perhaps because he has more first-hand experience with the medium than almost anyone, Biden has placed a significant amount of weight on Wednesday’s speech. Unlike some of his predecessors, who found the format staid and sought alternatives, Biden believes the venue is one of the traditional set-pieces of the presidency that can capture the office’s power like little else, according to an official.

“He was in the Senate for 36 years, he also sat through eight of these as the vice president, and he certainly recognizes important opportunity that this offers,” press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters on Tuesday.

In his years as senator and vice president, Biden was never called on to deliver as high-profile an address. But his methods of preparing for the moment haven’t changed much, according to people familiar with the matter. He still relies heavily on Mike Donilon, a longtime aide now serving as senior adviser, to help craft his message. Wednesday’s remarks are being spearheaded by his chief speechwriter Vinay Reddy, though Donilon is often the last person to read through Biden’s forthcoming speech.

Throughout the process, Biden urges his team to use direct and easy-to-consume language to convey often complex policy proposals. When a speech is nearing its final version, it is printed out in large font and compiled in a binder for Biden to mark up the text with slashes and other notes to aid in his delivery. The practice is borne from his lifelong stutter and helps him break up the text and avoid rushing.

In the past, Biden has edited speeches until the last moment, making changes on the airplane or limousine ride to a location and forcing aides to make adjustments in his teleprompter up until the last minute.

“The job of being a speechwriter for him is definitely not to put words in his mouth, it’s to take his words and just sort of package them up,” said Matt Teper, who worked as Biden’s speechwriter when he was vice president. “He’s got the right stories and got the right vibe. His brand and his tone are his, and you just sort of have to match him there. He’s the person who will define the speech in ways that I think a lot of other principals won’t.”

Seizing the moment

Before taking office, he promised to deliver the address to a joint session of Congress in February, but he and his aides ultimately decided to save the speech for a bigger moment, hoping to stir momentum to rally support for his agenda.

While Biden will use the speech to focus on his accomplishments, some of the unforeseen factors that have clouded his first 100 days will not escape mention. He will push for a new policing reform bill named for George Floyd amid a spate of police shootings of Black men. He is under pressure to do and say more on gun control after a series of mass shootings. And he still faces a troubling situation at the border, where his administration is scrambling to house a wave of unaccompanied minors.

Biden could use the address to announce a new cap on refugees after a tortured back-and-forth on raising the limit exposed divisions within his administration. Biden once promised to allow in more than 60,000 refugees but then backed off amid the border surge; after outcry, officials have spent the past two weeks urgently working to settle on a new figure to unveil quickly.

All state of the union speeches – or, as they are called in the first year of a presidency, simply an address to a joint session of Congress – feature a laundry list of items that agencies and departments around government send to the White House for inclusion. It is up to the President and his senior team to determine which warrant a mention in what is typically the most-watched presidential event of the year.

Foreign policy, which has been described as Biden’s “first love” by his aides, isn’t likely to occupy as much time in his speech as the pandemic and economic recovery, according to a person familiar with the matter, though he is still likely to mention he decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan by September 11.

Speaking after Biden will be Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, the Senate’s only Black Republican who the party selected to deliver its official response. Biden took on that job during President Ronald Reagan’s term, appearing with other Democrats in a compilation reel to air following the speech.

“We can criticize the Republicans and we will. We think, frankly, it’s time we put up or shut up,” Biden said in the 1983 version, strolling through his office in shirtsleeves. “As Franklin Roosevelt said during the recovery from the Great Depression, just four words are important now. These four words: It can be done.”

Decades in the making

Thirty-eight years later, Biden’s first time headlining the event will look dramatically different. Accompanying him Wednesday will be his wife, though there will not be a traditional first lady’s box of guests that past presidents have used to illustrate their policy proposals. Only a handful of aides will join him. Most Cabinet members will watch from afar, and with only his secretaries of State and Defense in the room, there won’t be a need for an official “designated survivor.” And a single Supreme Court justice – Chief Justice John Roberts – will represent the Judicial Branch.

Biden’s team planned in advance how he would wear his mask in the building: after being introduced he will walk down the center aisle with it on. Once he arrives at the rostrum for his remarks, he will remove his mask for the speech. After it concludes, he’ll re-mask for the walk out of the chamber.

It’s not likely how Biden envisioned his first presidential address to Congress in the decades he spent attending them as a spectator. After attending his first State of the Union in 1974 – one of the more famous ones, in which President Richard Nixon decried the Watergate investigation and declared he would never resign – Biden sounded unenthused speaking to a Delaware newspaper.

“It reminded me of an old-time Democratic speech. Was there anything he didn’t promise?” he said then to the Wilmington News Journal. “American people are grown up. Americans don’t want to be fed pablum.”

“The President – and the Democratic Congress, too – just don’t trust the American people enough to tell them the truth,” he went on. “We don’t need all those promises and non-spontaneous applause. What we need is a Churchill, a man with enough guts to stand up and say, ‘Look it’s going to be rough, but we can make it.’”

That isn’t far off the message Biden is expected to deliver this week. He has consistently said he plans to deliver news about the pandemic and economic recovery “straight from the shoulder” without sugarcoating the news.

Whether he forgoes “non-spontaneous” applause remains an open question; in his recent memoir, former House Speaker John Boehner said Biden made a pact with him ahead of one of Obama’s State of the Union speeches to “stop this jumping up and down and clapping,” only to back off the agreement when the speech came around.

“You know, I’m going to have to stand up sometimes,” Biden told Boehner, who described the vice president shooting him glances every time Obama delivered an applause line that seemed to say, “Is it OK if I stand up now?”

He said he understood.

“The last thing I wanted to do,” Boehner wrote, “was get ‘Uncle Joe’ in trouble with the President.”

CNN’s Jeff Zeleny contributed to this report.