Early in President Barack Obama’s second term, while fellow Democrats still controlled the Senate, the President asked Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to a private lunch at the White House.

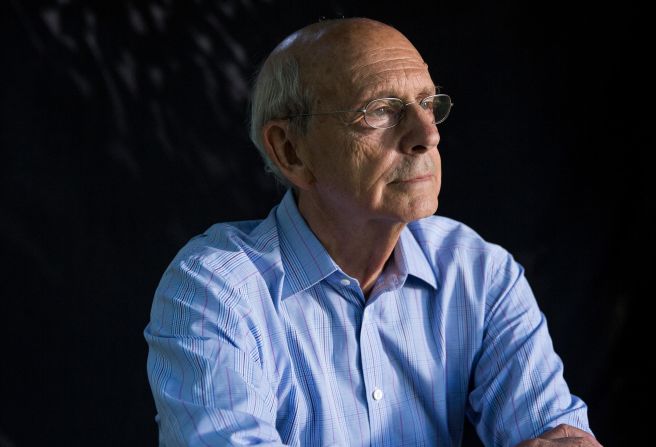

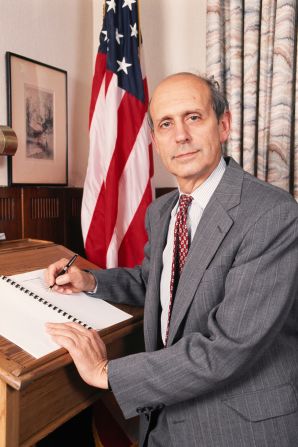

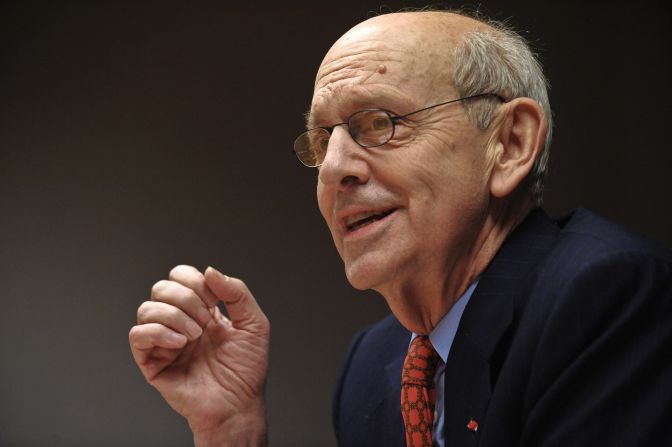

At the time, some liberals were calling for Ginsburg to step down to allow Obama to name a younger liberal, just as some Democrats today are urging Justice Stephen Breyer, 82, to retire and give President Joe Biden a chance to appoint a new justice.

The White House lunch, Ginsburg recalled months later in a 2014 interview, sped by and the justice, an unhurried eater, barely had finished her first course when the second arrived. The conversation ranged, but Obama never inquired directly about retirement.

Asked whether she thought he might have been fishing for any sign of her plans, the justice, already into her 80s, said no.

“I don’t think he was fishing,” Ginsburg said. Why had he summoned her? “Maybe to talk about the court. Maybe because he likes me. I like him. … If the President invites you, probably a part of you says, ‘Don’t question it. Just go.’”

Ginsburg died last September at age 87, giving then-President Donald Trump the opportunity to name a third justice to America’s highest court. Amy Coney Barrett took her seat just days before the November 2020 presidential election.

Now Democrats are eager to bring new liberal blood to the bench, as seen in all the columnists and social media wags targeting Breyer, a 1994 appointee of President Bill Clinton. The liberal Demand Justice group sponsored a mobile billboard truck last Friday to circle Capitol Hill urging Breyer to retire.

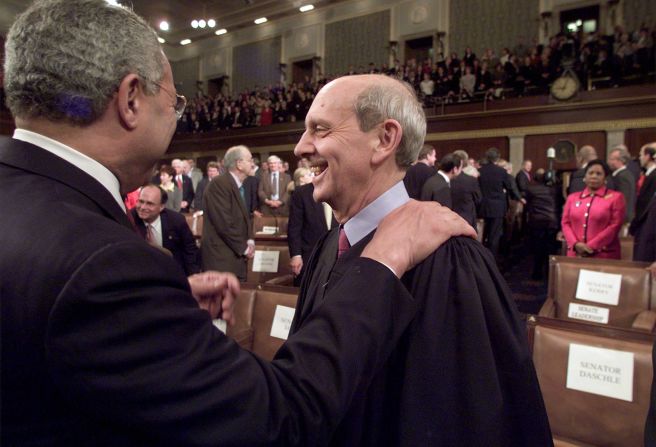

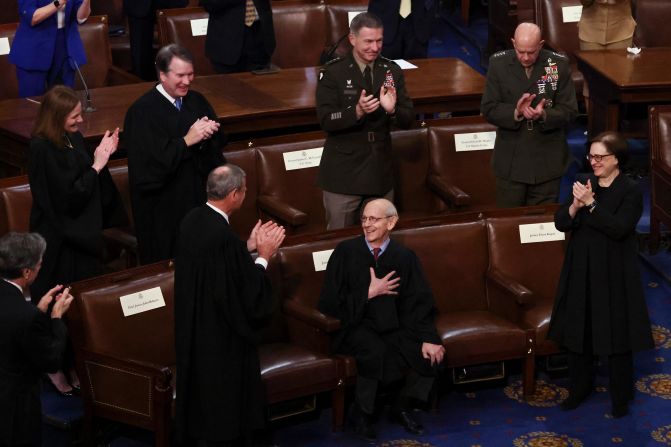

The atmosphere reflects the intense dynamic of Supreme Court successions, accelerated today by Republicans having attained three Supreme Court appointments and Democrats none in the last decade. The court is now divided between six Republican-appointed conservatives and three Democratic-appointed liberals. Among their pending cases, the justices are deciding the future of the Affordable Care Act, a clash between gay foster parents and religious interests, and access for organized labor on agricultural property.

There is no indication that Biden is pressuring Breyer to retire.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters last week she was unaware of any conversations Biden has had with Supreme Court justices since his inauguration and the President believes any retirement decision is Breyer’s to make “when he decides it’s time to no longer serve on the Supreme Court.”

Biden would not be the first president to angle for a chance to make a lifetime appointment. History is filled with examples by Democrat and Republican administrations, from the subtle to the blatant.

In 2019 and 2020, before Ginsburg’s health seriously declined, close supporters of Trump appeared to encourage Justice Clarence Thomas, now 72, to leave so Trump could add a younger jurist on the right. Some in the White House even told The Washington Post in 2020 they were preparing for his retirement. But the three-decade veteran Thomas has proved he has no desire to leave.

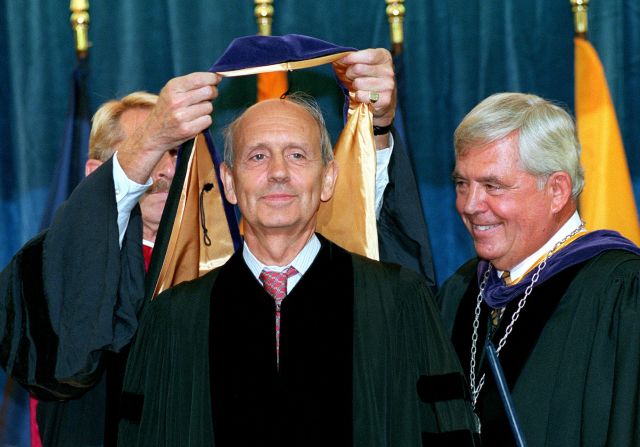

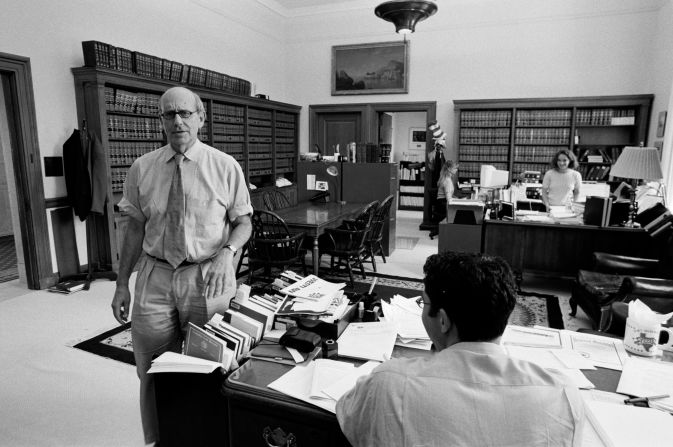

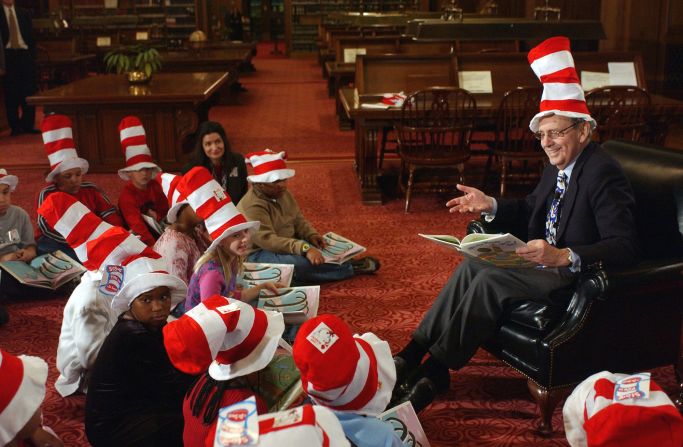

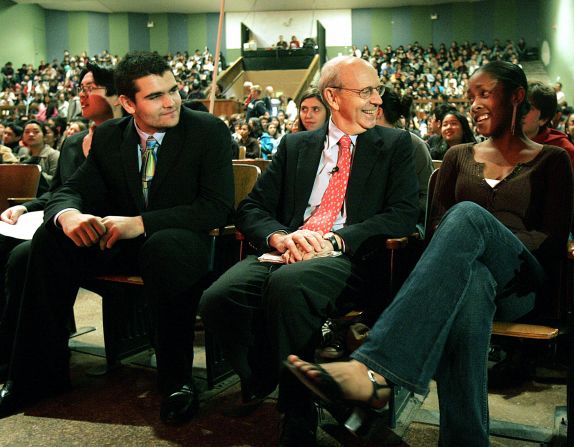

Breyer has declined to comment on his plans. He gave a lively two-hour speech on Supreme Court history and politics last week and appears in good health, engaged in his work.

He knows well the politics of Supreme Court retirements. He has served for more than a half century in various posts in Washington, including as counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee in the 1970s.

Washington appellate lawyer Deanne Maynard, who served Breyer as a law clerk in his first session on the bench from 1994-95, told CNN, “I’m sure Justice Breyer is well aware of the chatter about what his plans may be. But I’m also sure that he will make up his own mind about whether to retire and will do it on his own terms.”

LBJ’s masterful maneuvering

Under the Constitution, the Senate is responsible for “advice and consent” on judicial appointments. The chamber has a slim Democratic majority until at least the 2022 elections, and Breyer may be weighing whether to retire this year or next.

Years before Breyer’s Senate service, he witnessed first-hand the effects of presidential arm-twisting when he was a law clerk to Justice Arthur Goldberg during the 1964-65 session.

President John F. Kennedy had appointed Goldberg, then secretary of Labor, to the high court in 1962. Three years later, in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson persuaded Goldberg to step down and become ambassador to the United Nations. According to historical accounts, Johnson enticed Goldberg by emphasizing the role that the esteemed labor negotiator could take to end the war in Vietnam.

Johnson, a former Senate majority leader who could manipulate the levers of Washington politics, named Abe Fortas, a prominent attorney and close LBJ friend, to the Goldberg vacancy. The Vietnam War went on for another decade; Goldberg, who resigned from the UN post in 1968, later expressed regret that he had left the bench.

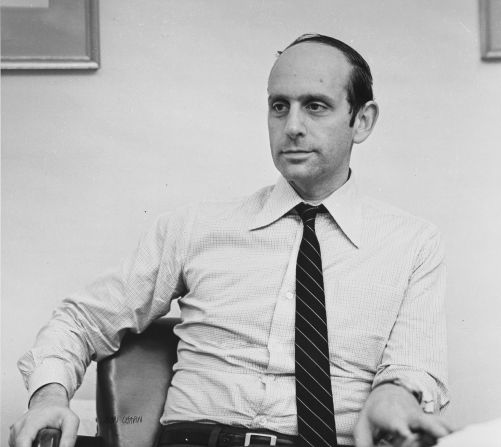

In 1967, Johnson hastened the retirement of Justice Tom Clark, who was just shy of 18 years on the bench, when he elevated Clark’s son Ramsey to be attorney general, a position that would have created a conflict of interest. (Ramsey Clark remained a civil rights advocate after leaving government; he died last Friday at age 93.)

Clark’s retirement led Johnson to select Thurgood Marshall as the nation’s first African American justice in 1967.

Such appointments constitute one of a president’s most enduring legacies. Biden has vowed to name the court’s first Black woman justice when the opportunity arises.

Opportunities can come suddenly, as the country saw in February 2016 with the death of Justice Antonin Scalia and in September 2020 with Ginsburg’s passing.

Sometimes, the opportunity never arises. President Jimmy Carter, who served a single term, from 1977 to 1981, failed to see a single Supreme Court vacancy.

Obama made two appointments in his first term (Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan), but his last nomination, in 2016, was blocked.

To succeed Scalia, Obama selected Merrick Garland, then a US appellate judge and now-attorney general, in March 2016. But Senate Republicans refused to act on the nominee, saying they were waiting to see who won the November presidential election that year.

Obama’s entreaty toward Ginsburg in 2013, when the Senate was still in Democratic hands, might have anticipated those Senate difficulties ahead.

Yet Ginsburg would not be pushed, either by the public pleas or by any subtle administration move.

“They’ve got a very good chef at the White House,” she recounted in the 2014 interview. “The problem for me is the President eats very fast. And I eat very slowly. I barely finished my first course when they brought the second. Then the President was done, and I realized that he had important things to do with his time.”