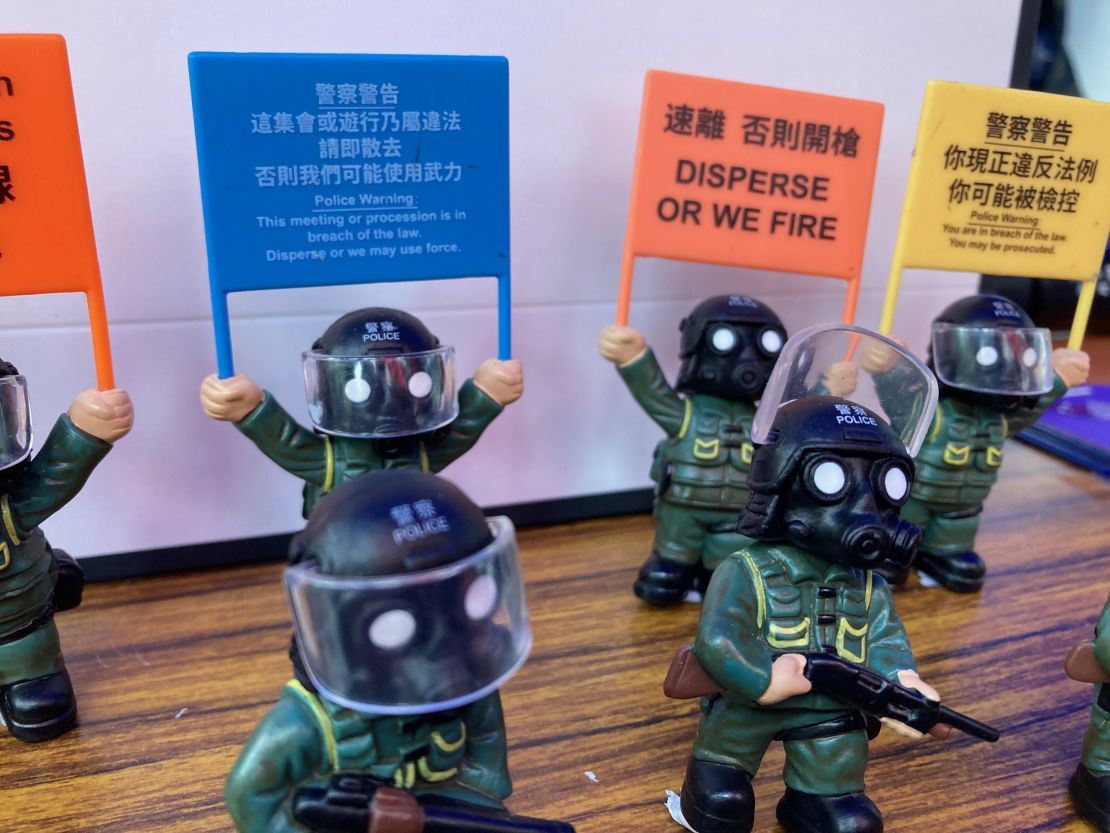

Riot police, heavily armored, their faces concealed behind masks, holding signs reading “Disperse or We Fire” and “Warning, Tear Smoke.”

It’s an image that has become synonymous with Hong Kong, a vision of the city which emerged from a summer of violent protests and a year of tightening political restrictions and mass arrests in the name of national security.

It’s also an image that’s indicative of a divided Hong Kong, evoking memories of police opening fire with thousands of rounds of tear gas, dousing protests with water cannon, and on several occasions, using live ammunition in response to often violent unrest.

For many, the sight of riot police represents a failed fight for greater autonomy and democracy under Chinese rule. On Thursday, these images were on sale as a souvenir, and pricey ones at that: $120 (880 HKD) for a pack of eight riot police figurines, replete with banners and weapons, released as the city marks the inaugural National Security Education Day.

The day was a celebration of the national security law, a piece of legislation imposed by Beijing on the special administrative region last June in response to the pro-democracy protests in 2019 that at times saw over a million people in the streets of a city of 7.5 million residents.

The law criminalized secession, subversion and collusion with foreign powers. People who are convicted of such crimes can face sentences of up to life in prison. And while the city’s leader said at the time of its passage that the law would only affect a handful of people, today almost every prominent opposition lawmaker and activist has been charged under it.

In a speech Thursday at the Police College, Hong Kong police commissioner Chris Tang accused foreign entities of having tried to “plant anti-China ideas in Hong Kong people’s hearts for their own political gains” and “use social issues to ignite Hong Kong local’s hatred for the government.”

These foreign forces specifically targeted young people Tang said, so the Hong Kong Police had tailored their message to children for National Security Education Day.

At the Police College, groups of elementary school-aged children could enjoy a kind of riot-police-theme-park experience.

The college parade ground became a kind of national security version of Disneyland’s Main Street, with the police band marching, a sometimes goose-stepping honor guard, a selfie station complete with cute cop balloon figures, and armored vehicles and water cannon trucks to inspect.

It all climaxed in a “kill the terrorists” live-action show, with hostages saved by automatic weapons shots, undercover Mercedes-Benz SUVs chasing an unmarked van and a SWAT team rappelling down from a helicopter to then take down the bad guys. Think “Hawaii Five-O” without the Hawaiian shirts.

Tang said without the national security law, “the city would have fallen deep into the abyss.”

As the helicopter swooped back in to airlift a wounded hostage to medical attention, end-of-show applause was muted. Many of the children in attendance turned their attention back to their cell phones or tried to get comfortable in face masks made more irritating by the rain falling on the parade ground.

As they hit the souvenir stand on the way out, the figurine set was likely out of range of grade school budgets, but other symbolic trinkets could be had for a tenth of the price or less, like tear-gas flag key chains, or Velociraptor medallions – a nod to the nickname of the black-clad, elite police units used to quell the more violent Hong Kong protests.

Anything the children did buy could be stuffed into their complimentary cloth National Security Education Day swag bags, suitable for use later to avoid the 50-cent charge for a plastic bag at Hong Kong supermarkets and retailers. To save money, and help the environment, the bags may be a message than endures.

Leading up to the day, there was one symbol that much of the local media had focused on and was ready to see, the Hong Kong police marching using the goose-step, the Prussian technique adopted by China and in various forms by some of history’s most authoritarian regimes.

The Beijing government had sent trainers to Hong Kong to get police and other uniformed government agencies started on mainland Chinese marching practices.

But as the honor guard came out to raise the Chinese and Hong Kong flags above the parade ground at the beginning of Thursday’s ceremony, they marched in the British style, as a force with a United Kingdom legacy might be expected to do.

Then suddenly, the honor guard switched to the goose step, but only for short time, less than a dozen paces. It was then back to British style to the flagpoles.

The movement seemed forced, unnatural and out of place. But to many observers, it may also have symbolized Hong Kong in 2021 perfectly.