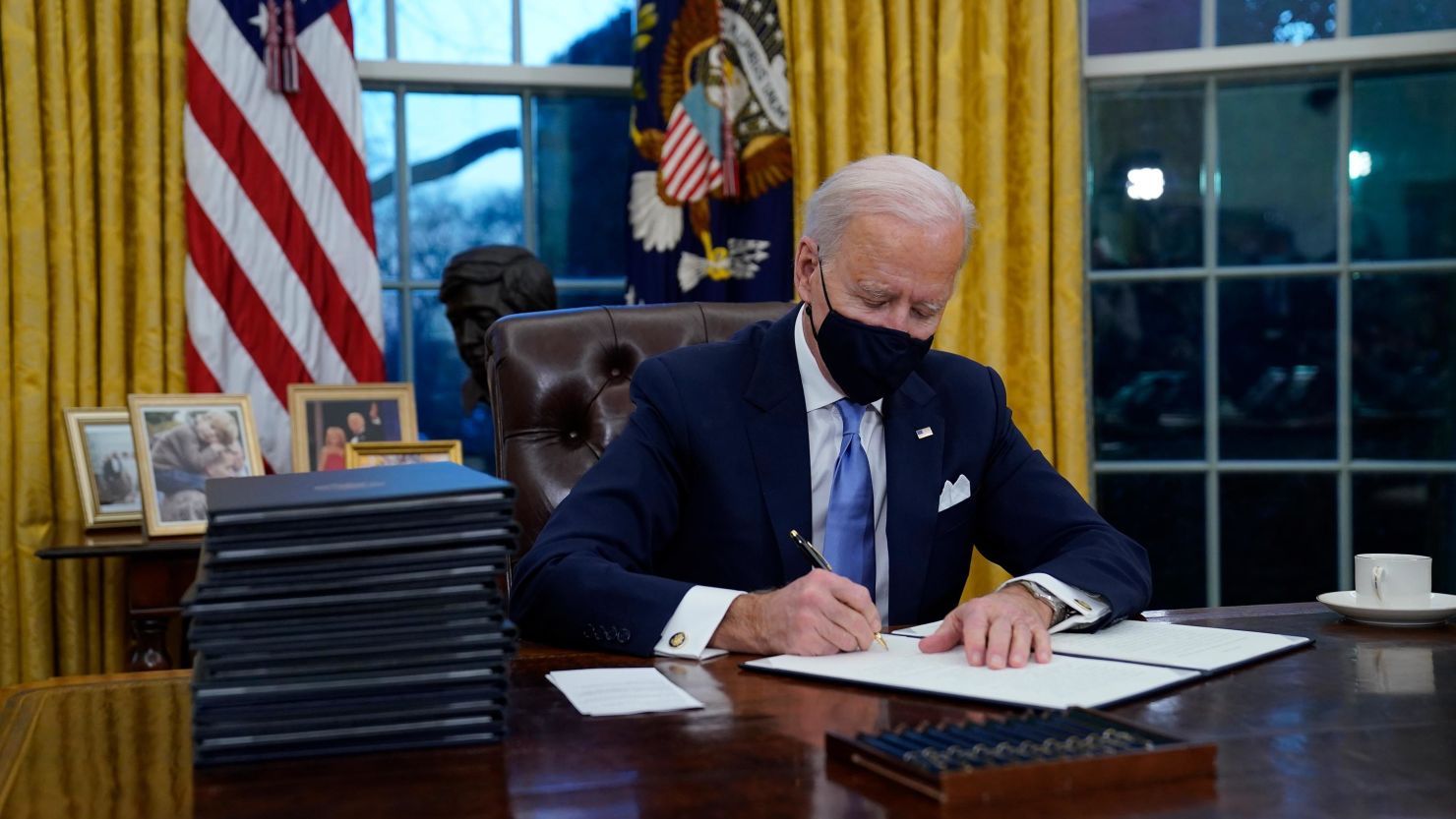

Even though President Joe Biden has moved to reverse many of his predecessor’s anti-immigration policies, the consequences of those restrictive measures linger and have contributed toa massive backlog of nearly 2.6 million visa applications.

The backlog includes nearly half a million applicants who are “documentarily qualified” and ready for interviews, according to a recent legal filing by the State Department. Backlogs in some immigrant-visa categories are 50 or even 100 times higher than they were four years ago, at the start of the Trump administration.

Some of the backlogs are due to restrictions imposed in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. But some also spring from pre-pandemic Trump policies or actions that the Biden administration hasn’t unwound.

The Biden administration is still reviewing or hasn’t fully reversed some measures that slow or block processing, such as heightened background checks and questionable terrorism designations.

In a policy reversal just Thursday, the State Department said that in places that are subject to regional pandemic travel restrictions, it will now let people seeking immigrant and fiancee visas go ahead and apply. Secretary of State Antony Blinken determined that “it is in the national interest” to exempt those applicants from the restrictions, a spokesman said.

Then, too, the effects of a Trump-era freeze on State Department hiring have left its consular sections short-staffed.

Meanwhile, Biden has come under fire from Democrats for not, as of Friday, raising the refugee cap for this fiscal year to 62,500, as his administration proposed back in February. Biden also proposed a target cap of 125,000 for the fiscal year starting in October, up from Trump’s 2020 cap of 15,000, the lowest level ever.

At a briefing on Thursday, White House press secretary Jen Psaki told CNN’s Kaitlan Collins that Biden remains committed to raising the cap to 62,500 by the end of the fiscal year, September 30, but she did not say when he’ll do so.

Expect impact into next year

Biden has revoked immigration restrictions ranging from a travel ban targeting mostly Muslim-majority countries to, on April 1, reversing a policy under which certain asylum or immigration applications were rejected if the applicant had left any blank spaces on their forms.

But immigrants and asylum seekers are discovering that the effects of the obstacles the Trump administration erected are likely to continue choking the flow into the US of legal immigrants and asylum seekers well into next year.

Leon Rodriguez, who served as director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services from 2014 to 2017, said he thinks it will take the Biden administration “a long time” to return to or surpass pre-Trump levels of immigration and refugee admissions.

“I don’t think you’ve ever had … as focused an effort on all fronts by the executive branch to reduce levels of immigration as you did from the Trump administration,” he said.

Melanie Nezer, a senior vice president at HIAS, a nonprofit that provides humanitarian aid and assistance to refugees, put it this way: “Picture a door like in New York City in the ’70s, with a hundred locks. The Trump administration locked all those locks. The Biden administration has to find all those keys, unlock those locks, and they can’t open the door until all that is done.”

The State Department, in an email to CNN, said that “backlog numbers will continue to fluctuate” depending on pandemic conditions at various embassies and consulates, and on the rate at which Homeland Security and US Citizenship and Immigration Services “approve additional petitions.”

Pandemic effect

To understand the challenges, consider the visa process. In March 2020, citing the Covid-19 pandemic, the State Department suspended routine visa services at embassies and consulates around the world. The next month, then-President Trump issued and twice extended a proclamation suspending the entry of most immigrants who didn’t already have valid visas until March 31, 2021. The State Department interpreted the bar on entry as also stopping it from issuing most immigrant visas, according to lawsuits against the agency. Although, by July, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo began letting consulates and embassies reopen for limited visa operations at the discretion of their local chiefs of mission, most stayed closed for all but emergency services, State Department legal filings show.

For security reasons, “you can’t adjudicate visas or passports from home,” said Michele Thoren Bond, a former State Department assistant secretary for consular affairs. “Anything passport, anything visa-related, you have to be in the office to do it; and to initiate visa cases you have to bring the applicants into the embassy for interviews, too. Even if you reopen, you can’t let them come in the numbers that would have been normal, pre-Covid.”

In legal filings, the State Department said that because of illnesses and other issues, after Pompeo gave posts the option to reopen, that next month, August, more than two thirds of the 143 US consular posts didn’t schedule a single immigrant visa interview. Even by January, a third of consulates and embassies still were unable to schedule a single interview.

A look at family-preference visas, which are issued to people seeking to join a relative already in the US, show how hard the pandemic restrictions hit a system already slowed by other Trump-administration moves.

In February 2017, just after Trump took office, there was a backlog of 2,312 family-preference visa applications, according to Rebecca Austin, assistant director of the National Visa Center at the State Department. Each of the next three years, that backlog more than doubled and doubled again, reaching 26,737 by Feb. 8, 2020. Then, due to the pandemic closures, by February 8 of this year, the backlog leaped to nearly 285,000, she said in a declaration to a federal court in California.

Visa interviews plummet

Documents filed in a visa lawsuit show that during the month of January 2020, before the pandemic, the State Department scheduled 22,856 family-preference visa interviews, worldwide. This past January, it scheduled 262 – a drop of nearly 99%.

Immigration attorneys in several visa lawsuits said the State Department continued to use temporary pandemic bans on entry from certain regions as a reason not to issue visas – even though a federal judge told the State Department last September that plaintiffs seeking to overturn that policy “are likely to succeed” in their claim that it isn’t in accordance with law. The department reversed that policy for immigrant and fiancée visa applicants on Thursday.

In a written response to queries from CNN, the State Department said that “embassies and consulates are working to resume routine visa services on a location-by-location basis as expeditiously as possible in a safe manner,” but that “We do not expect to be able to safely return to pre-pandemic workload levels until mid-2021 at the earliest.” Officials said health and safety measures would force them to “prioritize the most urgent and mission-critical cases” while scheduling fewer interviews than was normal before the pandemic.

Efforts to get back to pre-pandemic visa levels face another obstacle: Last fall, Pompeo expanded a pandemic hiring freeze on consular officers, saying that with fewer people traveling to the US, the State Department wouldn’t need them. State Department officials declined CNN requests to discuss the extent of the consular shortfall; but in January, Blinken told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the department had about 1,000 fewer employees than it had at the start of the Trump administration.

Because the Bureau of Consular Affairs relies mostly on visa and passport fees to fund its operations, the State Department said that the sharp drop in fee revenue from the pandemic “will have continuing effects on our staffing and available resources for several years, which means even when post-specific conditions improve, many posts will not be able to immediately return to pre-pandemic workload levels.”

House and Senate Democrats have proposed a budget that would let the State Department hire about 1,200 new Foreign Service officers, including consular officers. But even if that budget is adopted, hiring and training new consular officers can take a year and a half or longer, especially for those learning challenging languages.

“It’s a very, very big hole,” said Bond, the former assistant secretary for consular affairs. “It is super challenging. You are not issuing library cards here, you have to examine every application, in many cases you have to interview the applicant … there are checks that are being performed back in Washington; the whole interagency process, it is something that takes time.”

Lottery winners’ worries

State Department visa delays particularly worried those waiting to get or use diversity visas – up to 55,000 immigration visas a year that are awarded by lottery to qualified people from countries with low levels of immigration to the US.

Winning a diversity visa is always a long shot; in fiscal 2018, for example, nearly 14.7 million people applied for the lottery, giving each one odds of 1 in 267 of being selected and then getting a visa.

By law, diversity visas expire if they aren’t processed and issued in the same fiscal year. But as the pandemic closed US consular sections, the diversity-visa clock kept ticking

Aja Tamamu Mariama Kinteh, 33, a statistician from Banjul, capital of The Gambia, was thrilled when she won the visa lottery on her second try, in May 2019. (The diversity visa included her husband, a software designer, and their three children). She was offered a visa interview at the US embassy in neighboring Dakar, Senegal, on April 21, 2020, according to legal filings in a lawsuit against the State Department.

But then the pandemic closure pushed her interview to August. And then the Trump administration extended the immigration ban through the end of 2020 – far past the September 30 deadline for her to get her visa.

“I was devastated,” she said in a court declaration. “My whole family became heartbroken.” They’d sold their car and other property to pay for their fees and travel costs. Kinteh eventually joined a visa lawsuit in the US and got a court-ordered interview in September. But it wasn’t until February 19, when the federal district court in Washington D.C. issued an emergency injunction preserving and extending the validity of most fiscal year 2020 diversity visas, that Kinteh could be sure she and her family could actually come to the US. They arrived in March, and are now in the state of Washington, her attorney said.

On February 24, Biden revoked parts of the three presidential proclamations that had blocked entry of most immigrants. The next day, the State Department announced it would start processing immigrant visa applications again, and that it would reconsider cases of those who qualified for visas but had been denied because of the Trump-era proclamations.

Iran’s compulsory military service

But thousands of immigrant visa applicants from one country face yet another holdover obstacle.

An April 2019 Trump presidential proclamation declared the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to be a terrorist organization. That proclamation – which the Biden administration has not, so far, revisited – bars anyone who’s served in the revolutionary guards from being granted a US visa.

Iran makes military service compulsory for men; conscientious objection isn’t allowed. Men who don’t serve aren’t allowed to marry, to get passports, or to hold most jobs. Men have no choice in what military branch they’re assigned to – including the revolutionary guards, said Paris Etemadi Scott, legal director of the Pars Equality Center, an immigration services non-profit based in San Jose, California.

“We’re on board with banning terrorists and keeping IRGC on the terrorist organization list, but not with keeping a husband from joining his spouse because 40 years ago he did mandatory service with IRGC, and by way they don’t get to choose,” she said.

Ehsan Orojlou, 36, and a civil engineer in Tehran who is currently waiting for his diversity visa, is one of those hoping the Biden administration will clarify the terrorist organization designation of the IRGC so that it won’t prevent issuing visas to those, like him, who served in the guards only because they had no choice.

Orojlou said in a phone interview that he spent his obligatory military service typing letters and filing paperwork for the IRGC in Karaj, a suburb of Tehran, 14 years ago; and he said there are plenty of others like him. “Most of us are engineers, doctors,” he said. “We have not killed a cockroach; how on earth can we be terrorists, I don’t know.”

Sarah Vosseteig Bahiraei, a US citizen, was teaching in Turkey’s Cappadocia region when she fell in love with Afshin Bahiraei, a Christian refugee from Iran. They married in 2015; and, as CNN reported two years ago, their application for a spousal visa got caught up in Trump’s travel ban. Now, they have a daughter, Esther, born in Turkey – and they’re still waiting, because Afshin Bahiraei, too, did his obligatory military service with the IRGC. He suspects that’s why his visa application remains in the limbo of administrative processing.

The State Department declined to say whether it is re-examining who should fall under the bar on visas for members of the IRGC.

Some face other obstacles. Because the US and Iran don’t have diplomatic relations, Iranians have to travel to a neighboring country to apply for a US visa. Negar Bayati, a legal permanent resident who moved to the US in 2016 on a diversity visa, said that her husband Pooria’s March 2020 spousal-visa interview, scheduled at the US embassy in Abu Dhabi, was canceled by the pandemic closure. Now the US embassy has started issuing visa appointments again – but Abu Dhabi and the other emirates have their own pandemic travel bans from Iran and many other countries; and the US embassy there has turned down Bayati’s and her husband’s request to have the case moved to another US embassy in that region, she said.

“It’s a crazy situation,” Bayati said. “It’s been a horrible year for me. I thought my husband was going to be here last March.”