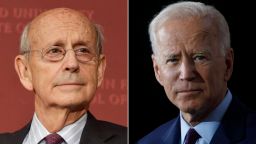

Justice Stephen Breyer, who may be nearing the end of his Supreme Court tenure, expressed concern on Tuesday about the standing of the high court and the possible erosion of public confidence in its decisions.

In an expansive, two-hour lecture at Harvard Law School, Breyer bemoaned the common practice – by journalists, senators and others – of referring to justices by the presidents who appointed them and of describing the nine by their conservative or liberal approach to the law.

“These are more than straws in the wind,” the 82-year-old Breyer said. “They reinforce the thought, likely already present in the reader’s mind, that Supreme Court justices are primarily political officials or ‘junior league’ politicians themselves rather than jurists. The justices tend to believe that differences among judges mostly reflect not politics but jurisprudential differences. That is not what the public thinks.”

Breyer also warned against proposals to expand the size of the Supreme Court from its current nine members. Public trust was “gradually built” over the centuries, he said, and any discussion of change should take account of today’s public acceptance of the court’s rulings, even those as controversial as the 2000 Bush v. Gore case that settled a presidential election.

“The public now expects presidents to accept decisions of the court, including those that are politically controversial,” he said. “The court has become able to impose a significant check – a legal check – upon the Executive’s actions in cases where the Executive strongly believes it is right.”

He said people “whose initial instincts may favor important structural … changes, such as … ‘court-packing’” should “think long and hard before embodying those changes in law.”

Court expansion proposals have been raised by liberal advocates disheartened by the long building conservatism of the Supreme Court and its relatively new 6-3 conservative-liberal makeup, since last fall’s death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and former President Donald Trump’s selection of Amy Coney Barrett to succeed her.

Breyer is one of the three liberals, yet he emphasized on Tuesday he believes his differences with colleagues are jurisprudential, rather than based on ideology or politics.

The court’s six conservatives were appointed by Republican presidents, the three liberals by Democratic presidents. Breyer said in his speech that decades earlier such political references would not have been part of news coverage. But decades earlier, there was not such neat political and ideological symmetry.

Republican appointees, such as Justice John Paul Stevens, a 1975 choice of President Gerald Ford, ended up voting with the liberal wing of the bench. Stevens, who retired in 2010, was the last of his kind in this modern era, when presidents carefully screen for ideology and justices rarely break expectations.

He also lamented the state of today’s Senate screening of judicial candidates.

“The Senate confirmation process has changed over the past two or three decades, becoming more partisan with senators far more divided along party lines,” he said. “Senators will often describe a nominee they oppose as too ‘liberal’ or too ‘conservative.’ What they say, reported by the press to their constituents, reinforces the view that politics, not legal merits, drives Supreme Court decisions.”

Retirement rumors

Breyer’s speech, delivered as he stood against a Harvard Law crimson backdrop and carried over Zoom, reflected his own broad reading of constitutional guarantees, as well as his aspirations and fears for today’s judiciary.

Breyer has written some of the most forceful opinions attempting to preserve landmarks on abortion rights and school desegregation. Unlike his colleagues on the right wing, he has also endorsed the broad regulatory power of government to protect workers, consumers and the environment.

A former law professor who never lost his academic air, Breyer devoted most of his speech to the high court’s roots of power before delving into some of his current concerns. “It’s a long lecture,” he warned at the outset of the event, noting that he would take a break midway through.

He wove in references to his Capitol Hill service for the late Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy in the 1970s and concluded with references to Albert Camus’ “The Plague,” a favorite of Breyer’s even before the country was seized by the coronavirus pandemic.

Since President Joe Biden’s January inauguration, Breyer, who was appointed to the bench in 1994 by Democratic President Bill Clinton, has seen regular news commentary by fellow Democrats urging him to retire while Biden has a Democratic majority in the Senate, if only by the current one-vote margin.

Breyer has declined to talk about his retirement prospects and on Tuesday avoided the topic altogether.

If Breyer, the eldest of the nine, does announce his retirement in upcoming months, he would give Biden an opportunity to appoint the country’s first Black woman justice, as Biden has vowed. That would likely not change the ideological makeup of the bench, but it would enhance its diversity and relative youthfulness.

Dissents are a ‘failure’

Tuesday’s Harvard lecture was part of an annual event in honor of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Breyer advocates a judicial approach that expansively interprets the Constitution, the opposite of Scalia’s method, known as originalism, tied to the 18th Century understanding of constitutional guarantees.

Yet Breyer and Scalia, who died in 2016, were friends and in Tuesday’s lecture, Breyer joked about their appearances on the law school circuit.

In his nearly 27 years of service on the high court, Breyer has tried to bridge relations with conservatives, saying he abhors dissents and considers them a “failure.”

Some of Breyer’s most compelling opinions, it should be noted, have been written in dissent. In 2007, for example, he objected to an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts rejecting school integration plans in Seattle and Louisville. Roberts said districts could not consider a student’s race when making school assignments to reduce racial isolation throughout the school district.

“This is a decision that the Court and the Nation will come to regret,” wrote Breyer, whose father, Irving Breyer, was a long-serving school board member in San Francisco. Breyer still wears the wristwatch his father received upon his retirement from the district. Breyer said the Roberts opinion threatened “the promise of” the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Breyer said Tuesday that differences with his colleagues were based on their distinct views of the structure of the Constitution or how they interpreted statutes. He did not refer to instances in which his colleagues themselves have publicly questioned each other’s motives.

Breyer did allow that sometimes justices weigh public opinion or the future ramifications of a decision. And he acknowledged that the nine are products of their individual backgrounds and experiences.

Still, he said, “judicial philosophy is not a code word for ‘politics.’”