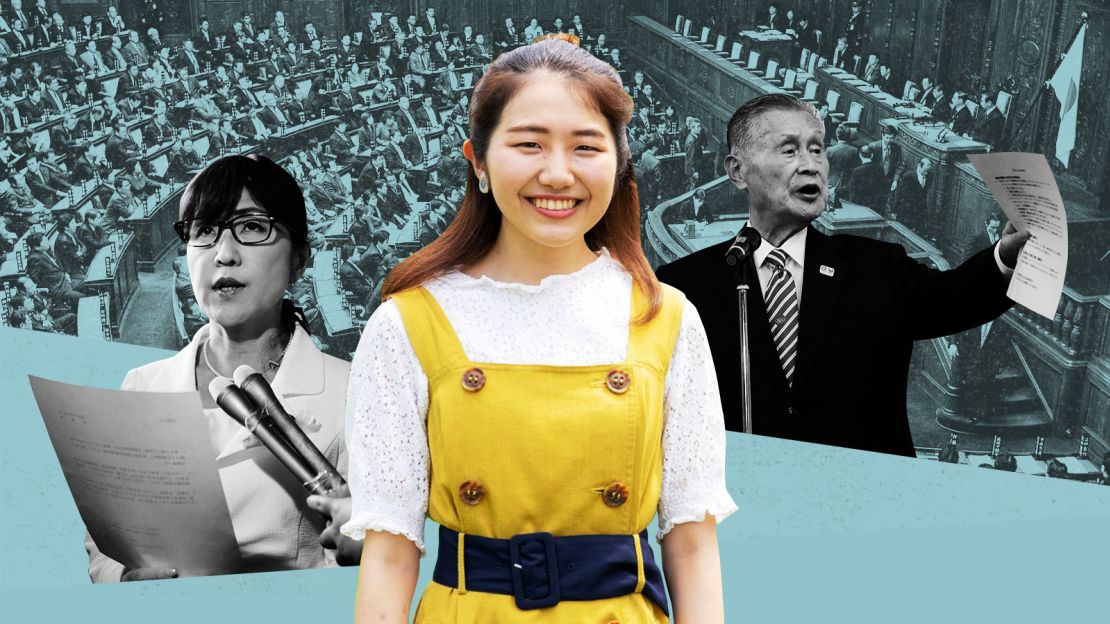

There was the Tokyo 2020 official who floated the idea of an “Olympig” creative campaign with plus-sized model Naomi Watanabe. An Olympic chief who resigned after making sexist remarks about women.

And a Japanese governor who recommended men go grocery shopping during the pandemic because women take too long.

Just last week, a Japanese city manager sparked outrage when he gave a speech telling new employees to “play around” to remedy the country’s plunging birth rate.

For decades, gaffe-prone men in positions of power have caused embarrassment and sparked outrage among younger generations and women in patriarchal Japan, which is ranked 120 out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap Index – between Angola and Sierra Leone.

As of 2020, only 15% of senior and leadership posts were held by women, according to the Global Gender Report. And with only 14% of seats in Japan’s parliament occupied by women, and most lawmakers aged between 50 to 70, male boomers dominate political and business life in the country.

Experts say some men of that generation carry beliefs that women are best left at home, or should attend meetings but remain silent.

But Momoko Nojo, a Tokyo-based economics student, says those views have driven a generational wedge between the political gerontocracy and young people born in the 1990s, an era of economic stagnation dubbed the “lost decade.”

As a 23-year-old woman prepared to agitate for change, Nojo runs“No Youth, No Japan,” a student-led social media initiative founded in 2019 with more than 60,000 followers on Instagram, which promotes political literacy and aims to persuade a largely disenchanted youth to use their votes to influence the future.

“We are sharing information on online platforms such as Instagram because we want young people to make their voices heard and their votes count,” said Nojo.

Generational divide

From the late 1940s to the late 1980s, Japan turned its economy around. Powered by male white-collar workers, the country became the world’s second-largest economy after the United States.

Born in the late 1930s, older leaders, such as former Tokyo 2020 head Yoshiro Mori and an official from Japan’s ruling party Toshihiro Nikai, who recently sparked international condemnation for their sexist remarks on women, are from a generation who brought Japan to the global stage after its defeat in World War II, according to Kukhee Choo, an independent Japan-based media scholar.

During the economic miracle, women were largely relegated to the domestic sphere or occupied clerical and secretarial roles in offices, largely due to attitudes at that time.

“(The older generation) think back then society worked better and the economy was better – there’s that arrogance,” said Choo.

Mori and Nikai both said women should remain silent. Choo says their disparaging remarks toward women were examples of traditional and outdated views on the place of women in society, which suggest men should remain the primary breadwinners and women should stay home.

But Nojo, the student activist, says young people face a different reality in Japan compared to the one the boomers lived through.

While white-collar workers were ensured lifetime employment when Japan’s economy thrived, today, many working adults face an unstable job market, snail-pace salary growth, and the prospect of never being homeowners.

“It’s been almost 20 years since the bubble burst, but it’s becoming harder for us to see a bright future where we can chase our dreams,” said Nojo.

For instance, over the past decades, Japan has seen a dramatic increase in part-time and temporary employment – due, in part, to the partial legalization of temporary and contract work in 1986 and full legalization in 1999.

In 2019, Japan had 22 million part-time and temp workers, compared to 17 million in 2011, according to the country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

That same year, 39% of women in the workforce were employed part-time compared to 14% of men. This leaves women at an unfair disadvantage as non-regular workers earn about 40% as much as regular workers on an hourly basis and receive less training in their workplaces, according to a report from the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development.

“We do feel anxious about the future and wonder if we’ll get a stable job that pays us enough to raise kids. Will we get the same salaries that our parents had? Will we even get pensions? We are a generation with all those kinds of worries,” added Nojo.

Traditions die hard

Tomomi Inada, a former defense minister, says the male old guard’s disparaging attitudes toward women symbolize problems with Japan’s power structure, where women and minorities still have scant representation.

Government plans to put women in 30% of senior management roles by 2020 across the workforce were quietly pushed back to 2030 last year, after it proved too ambitious.

And in Japan, only one in seven lawmakers is a women – that’s fewer than 14%, compared to a 25% global average and 20% average in Asia, as of January 2021, according to data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, an organization that compiles data on national parliaments.

The problem, says Inada, is the widespread belief that politics is still a man’s world. “The notion that good women understand how to behave and don’t push themselves forward still exists today,” she said.

Inada has backed enforced electoral quotas that propose to make 30% of candidates for elections in Japan’s ruling party female. She argues that increasing female participation raises responsiveness to policies concerning women and is also beneficial to men.

But it’s not always easy to shift the mindsets that bind people to traditional gender roles in Japan, according to Nobuko Kobayashi, a partner with EY-Parthenon, a strategic consulting group within E&Y Transaction Advisory Services.

“When the idea of being one step behind a man is ingrained in your brain from early on, it’s tough to break when you’re an adult,” said Kobayashi.

Last month a Kyodo News survey found more than 60% of active female lawmakers thought it would be difficult to boost the numbers of women in parliament up to 35% by 2025.

From clicktivism to activism

Last month Japanese broadcaster TV Asahi sparked outrage with an advert featuring a female actress saying “gender equality is outdated.” The network later apologized and took the commercial down following a Twitter storm.

Twitter has long been the dominant social network in Japan, with over 51 million active users. It’s the social media site’s second-largest market globally, behind the US, according to a 2020 report from Hootsuite, a social media marketing company.

The large user-base has resulted in a plugged-in generation of younger Japanese like Nojo, the student activist, who are airing their grievances online and holding those in power accountable for their actions and words.

“The political dinosaurs were pretty clueless about all this, but they’re suddenly realizing,” said Jeffrey Kingston, a Japan expert at Temple University.

Kingston gives the example of the backlash that ensued on social media when Mori, the former Tokyo 2020 head, tried to handpick another octogenarian man as his successor. That move ultimately failed when he was replaced by former Olympian Seiko Hashimoto, a 56-year-old woman.

Kathy Matsui, a former vice-chair and chief Japan strategist for global investment bank Goldman Sachs, said while sexist comments were swept under the carpet 10 years ago, now “foot-in-the-mouth” comments are inexcusable. “Because of social media, you can’t get away with it that easily,” she said.

In recent years, campaigns such as #MeToo and #KuToo – which saw women petition against wearing high heels to work – have put Japan’s gender inequality and human rights issues in the spotlight, even though the movements failed to garner as much support in the country as they did in the West.

Changing of the guard

Matsui, the former banking strategist, says many young men in Japan who do not share the traditional values espoused by their fathers and grandfathers are also taking to social media to amplify women’s voices.

What’s more, young people dislike male public figures who make derogatory comments because they see it as symbolic of what often happens in the workplace, said Koichi Nakano, a political science professor at Sophia University. “They think, ‘I know that guy,’ and he shouldn’t just be getting away with it,” he added.

But Nakano argues that not all controversial remarks from the top result in dismissal. For instance, Mori’s resignation earlier this year came as the public’s skepticism toward the Olympics grew. “Ministers often make ill-advised, offensive comments in Japan but they often get off the hook. But people understand that when the conditions are right, protesting on Twitter can be effective,” he said.

Though Mori’s ouster marked a watershed moment, the battle to make Japan a more diverse and gender-equal society is far from over.

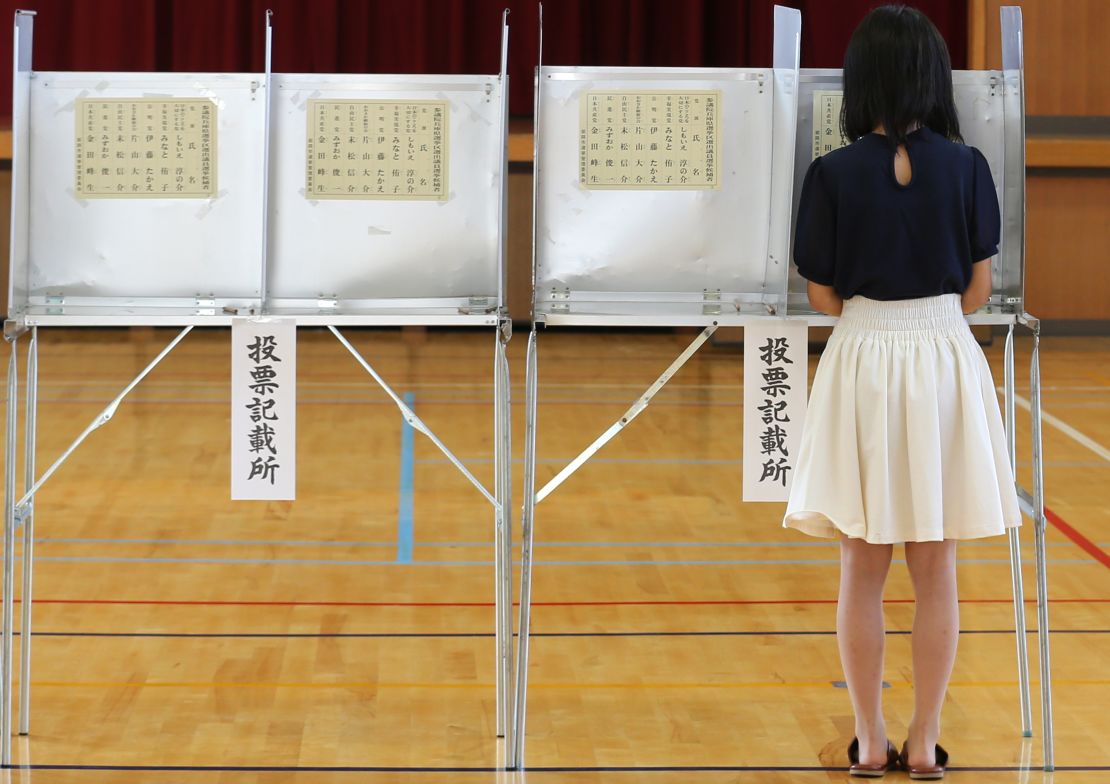

In 2015, a new Japanese law lowered the minimum voting age from 20 to 18, marking the first such change in over 70 years when the age was reduced from 25. That new legislation allowed around 2.4 million 18- and 19-year-olds to exercise their democratic rights in the national election for the first time in 2016.

However, the turnout was lower than expected, with only 46.8% of 18- and 19-year-olds taking part. The figure fell to 41.5% in the lower house election the following year.

Nojo said Japanese youth are less involved in politics than their counterparts in the US and Europe, as they feel disenchanted with the status quo and don’t bother voting, while those who do tend to lean right.

“In Japan, many people are conservative. If you take America, young people support Biden and in Europe, young people are liberal, whereas in Japan, people in their 20s don’t go to the polls. They’re suspicious of politics and politicians,” she said.

Kaname Nakama, a fourth-year student at Meiji University in Japan, who identifies as a conservative and runs a political YouTube channel, said young people in the country think politics is too complicated.

He discusses political issues ranging from the role of the media in Japan to geopolitics during a Joe Biden presidency. He said younger conservatives find outdated remarks made by older men in positions of power “embarrassing” and his peers don’t believe women should stay at home.

For Nojo, Mori’s ouster set a precedent. However, she wants older men of the ruling elite to reflect more on their behavior and the need for greater representation of women in positions of power. She added that the issue is never about one, outdated man at the top, but the need to reform the behaviors and systems that prop them up.

“It’s really about problems at the heart of organizations – and also Japanese society,” said Nojo.