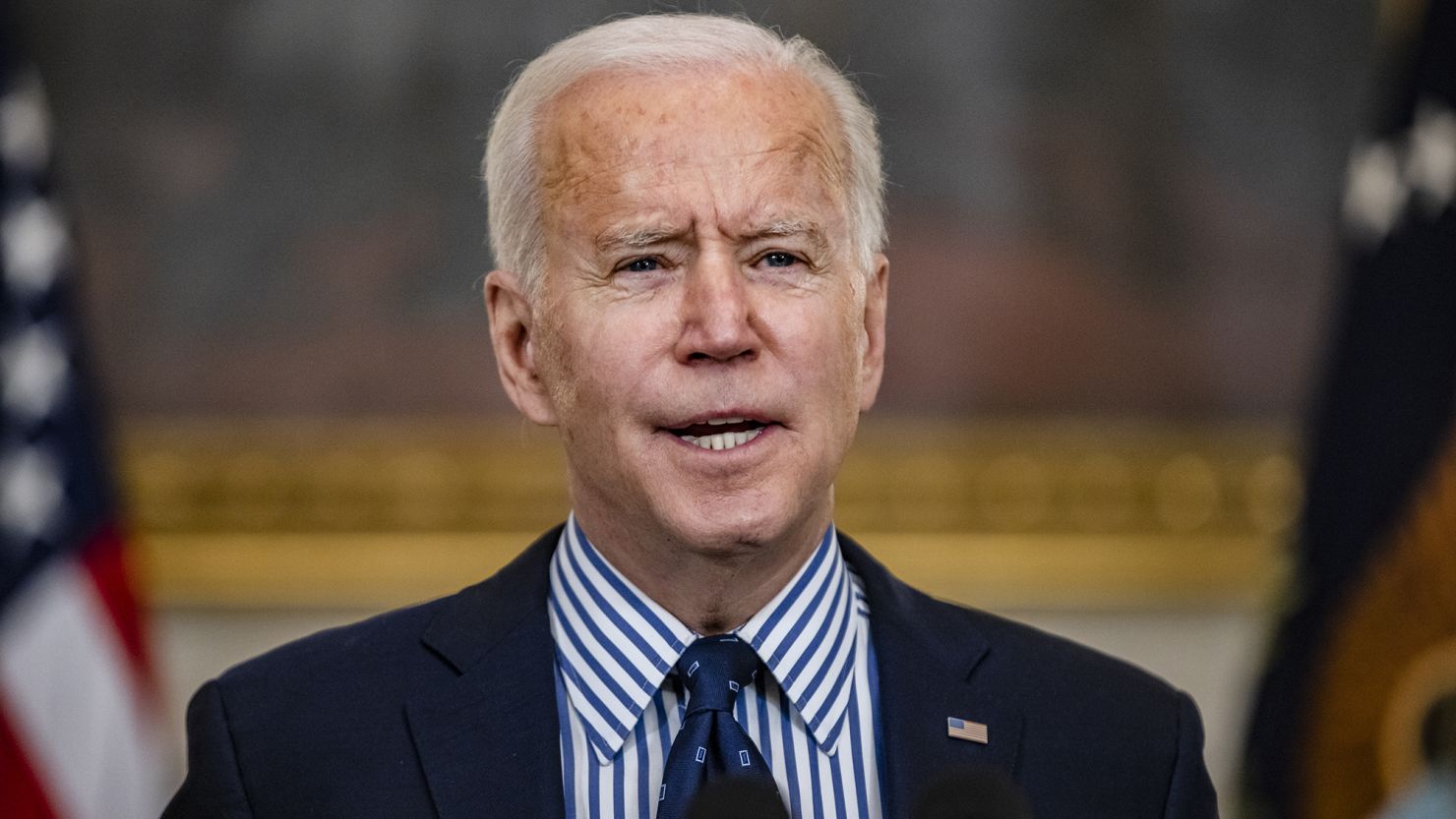

Joe Biden is on the cusp of a presidency-defining first 100 days victory and tens of millions of Americans could soon get stimulus checks as the $1.9 trillion Covid-19 rescue bill heads back to the House for a final vote.

After a weekend of high Washington drama, which saw the President intervene to keep moderate West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin in line with his fellow Democrats and preserve their tiny Senate margin, Biden hopes to sign the massive bill into law this week.

That will depend, however, on House Speaker Nancy Pelosi preserving her own narrow margin to pass the bill ahead of an expected House vote on Tuesday. Progressive Democrats are disappointed by the removal of a minimum wage hike in the Senate version of the package passed on Saturday and the narrowed scope of unemployment payments.

The bill includes extended help for the unemployed, money to reopen schools, aid for stricken small businesses, child tax credits and health insurance subsidies. It would enshrine one of the boldest deployments of federal power to alleviate the plight of the poorest Americans in at least a generation, and would invite comparisons between Biden and great reforming Democratic presidents of the 20th century, on a crisis measure uniformly opposed by Republicans.

In addition to its short-term impact, proponents of the bill say it has the potential to significantly cut child poverty and improve health care for many Americans – results that would not normally be expected in an economic stimulus bill. Many of the benefits available under the legislation are fairly short term – unemployment benefits expire in September and child tax credits only last a year.

But advocates view the credits and health subsidies as a breakthrough years in the making and as a stepping stone to a permanent infrastructure that will be politically difficult not to extend at least under Democratic congressional majorities. The moves have the potential to significantly cut child poverty and improve health care for many Americans – results that would not normally be expected in an economic stimulus bill.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, a liberal icon and independent who votes with Democrats, offered Biden some political cover among House progressives when he described the bill on Saturday as “the most significant piece of legislation to benefit working families in the modern history” of the US.

When the President signs the bill, he will claim a genuine achievement early in his presidency that will validate the organizing principle of his campaign and his promise to the American people – that he could secure the resources and strategy that he says are needed to end the pandemic.

“When I was elected, I said we were going to get the government out of the business of battling on Twitter and back in the business of delivering for the American people,” Biden said on Saturday.

A warning sign for Biden

But the laborious process of shepherding the bill through the Senate while balancing the aspirations of moderate and more liberal Democrats offered a warning about how hard it will be for Biden to enact the rest of his ambitious agenda, including on a voting rights bill that the House has already passed and future measures on climate change and immigration.

In a separate move on Sunday, the President signed an executive order designed to expand voting access as scores of Republican lawmakers in multiple states draw up legislation to suppress the vote, much of which appears to directly target minority voters.

The Covid rescue plan only got through the Senate Saturday after a prolonged period of limbo as Democratic leaders negotiated with Manchin on tightening the timeline of extended federal unemployment benefits and a cap on their non-taxable treatment.

Senate Democrats were able to advance the rescue bill using a procedure known as reconciliation, but some are already contemplating whether to amend or abolish filibuster rules that allow Republicans to block major legislation that lacks a 60-vote supermajority that is well out of the reach of Democrats.

But the reluctance of eight Democrats to back an effort by Sanders to insert a minimum wage hike in the bill raised doubts about the solidity of support in the caucus for the no-turning-back moment of abolishing the filibuster.

White House communications director Kate Bedingfield said on CNN’s “State of the Union” Sunday that the President, who spent three-and-a-half decades in the Senate, still hopes to jointly pass key legislation with Republicans.

“His preference is not to end the filibuster. He wants to work with Republicans, to work with independents. He believes that we’re stronger when we build a broad coalition of support,” Bedingfield insisted.

Manchin in the middle

Manchin is constantly balancing his own political realities in a conservative home state won overwhelmingly by ex-President Donald Trump and the pressure of being part of the Democratic caucus. But while many progressives were furious with the West Virginia Democrat’s actions on the eve of the bill’s passage in the Senate, Biden wouldn’t have had the votes without him. Manchin denied on Sunday on CNN that he had made the bill less helpful to millions of struggling Americans despite securing a cap on tax-free treatment of federal unemployment benefits and by ending the extension of the benefits on September 6, three weeks earlier than Democrats had hoped.

“All I did was tried to make sure that we were targeting where the help was needed,” Manchin told Jake Tapper on “State of the Union.”

“Right now, we’re getting $300 to people who are unemployed by no fault of their own. I want that to continue seamlessly.”

CNN reported that Biden, who ran for the presidency arguing that his long Senate experience would help him close deals on big bills, spoke to Manchin on Friday during the prolonged standoff. A source with knowledge of the conversation said the President listened to the West Virginia senator’s concerns and gave him space so as not to add to pressure on him. With Manchin wielding extraordinarily effective power as a potential swing vote in the Senate, it is unlikely to be his last such discussion with a President who has big plans but a tiny margin of error to implement them.

The weekend Senate duel over the Covid relief bill was also the first significant test for the GOP’s evolving position of unified opposition to Biden’s agenda. While the President came to power pledging to work with Republicans, especially in the Senate, he judged a rival $600 billion proposal drawn up by a group of GOP senators to be insufficient for the magnitude of the current crisis. He still hopes for cooperation in other areas – like infrastructure reform.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell argued last week that falling numbers of new coronavirus infections and the increasing success of the vaccination effort meant that the relief package was too large.

But Republicans are taking a political risk. They opposed Biden’s bill despite its broad popularity in the country and signs Americans are satisfied with the way the President is addressing the pandemic, as daily Covid-19 vaccinations approach 2.5 million per day.

Republicans, apparently hoping the rescue bill will prove less popular down the road and keen to deprive the President of a bipartisan victory, have claimed the package is packed with irrelevant spending.

“When people find out what’s in this bill, they’re going to lose a lot of any enthusiasm they may have for it right now because this was not really about coronavirus in terms of the spending,” Wyoming Republican Sen. John Barrasso said on NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Sunday. “This was a liberal wish list of liberal spending just basically filled with pork,” Barrasso said.

And one of the GOP governors who prompted the President last week to condemn “Neanderthal thinking” on premature openings told CNN on Sunday that it was time to get businesses rolling again, even as experts warn that Covid-19 variants could explode in the coming weeks.

“All of these individuals who, for a year have said, ‘follow the science, follow the data,’ now want me, when things are going down, to completely ignore the data,” Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves said on “State of the Union,” citing a daily average of new cases in his state of 450, well below the national average.

Despite the Republican pushback, an ABC News poll published Sunday found that 68% of Americans approve of the way that Biden is handling the crisis.