Jack Ma’s Ant Group quickly became one of China’s most powerful companies, and its plans for bridging the worlds of tech and finance were growing ever more ambitious by the day.

Now it appears to be turning into the kind of highly regulated Chinese bank that it hoped to supplant.

Months after the company’s blockbuster initial public offering was shelved at the last minute — a move that appears to have been sparked by Ma’s criticism of Chinese regulators — several media outlets have reported that Ant has agreed with authorities to become a financial holding company.

Ant declined to comment on those reports earlier this month, and the details of any potential agreement were not immediately clear. The company did not respond this week to additional questions about any deal with authorities.

But the reports suggest that the Alibaba-affiliated company may now have to follow rules similar to those required of traditional Chinese banks — a move that could force it to scale down its aspirations to be a dominant force in the tech world.

The company is best known for its Alipay digital payments app, which boasts more than 700 million active users every month. It also has massive interests in online investing, insurance and consumer lending, which have helped it grow into business with assets worth about $635 billion under management.

While the company was largely able to grow unchecked over the past decade, the political winds in Beijing are changing. Authorities are growing increasingly mindful of how much influence Ant and its peers have on the country’s financial system — Ant, for example, now commands more than half of the mobile payments market in China — and are looking for ways to rein them in.

“The Chinese government is moving to regulate these apps with a much heavier hand,” said Doug Fuller, an associate professor at the City University of Hong Kong who studies technological development in Asia. “The aim is not to kill these apps, but the days of unrestrained growth and hopes of displacing traditional banking some day are over.”

What it means to be a bank

Beijing’s tech crackdown has taken many forms over the past several months. Not only did regulators force Ant Group to call off its record-breaking IPO, they also launched an antitrust investigation into Alibaba (BABA), questioned executives at Tencent (TCEHY) and Pinduoduo (PDD), and floated new rules that could govern the operations at many tech firms.

While several loose ends remain, there are some clues as to what Ant’s ultimate fate may be, at least. The People’s Bank of China last September outlined new measures for financial holding companies that required them to hold “adequate capital” matching the amount of assets they have, among other measures.

If Ant is now classified as one of those companies, that could mean it will either have to significantly increase the amount of cash it holds in reserve, or otherwise slash the size of its consumer lending business.

Even though the details of Ant’s reported agreement have not yet been confirmed, it’s easy to see why these new rules might be a problem.

Ant held about 2.15 trillion yuan ($333 billion) worth of consumer and small business loans as of last June, according to its IPO prospectus. By comparison, more than 4,000 commercial banks in China held just six times as much in outstanding loans at the time, according to data from the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank.

Against that huge loan book, Ant held just 16 billion yuan ($2.5 billion) in authorized capital.

Beijing, meanwhile, mandates that “systemically important” banks, or those deemed too big to fail, have enough money to cover at least 11.5% of their risk-weighted assets — a rule it adapted from a widely used international banking guideline called the Basel Accord. Ant’s balance sheet falls far short of that ratio. (Notably, China’s ratio is even stricter than that used by other countries that follow Basel.)

On Saturday, regulators announced even more new rules that could dampen Ant’s growth. Online lending companies like Ant will from next year be required to put up at least 30% of the funding for any loan they issue in partnership with a bank according to the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Ant contributed just 2% in funding to the more than $260 billion in consumer loans they issued jointly with banks as of last June, according to stock exchange filings.

Ant will have “less flexibility and innovative space,” if it becomes a financial holding company, wrote Ji Shaofeng, the chairman of the China Small and Micro Credit Industry Research Association, in Caixin Global magazine last November after the IPO was pulled. He added that the large amounts of consumer data that Ant has collected through its digital payments services could also now fall under the watchful eye of regulators, potentially presenting further challenges.

“For a tech company that needs constantly [to] innovate, such regulations will pose extremely big pressure,” he wrote.

Longstanding public tensions

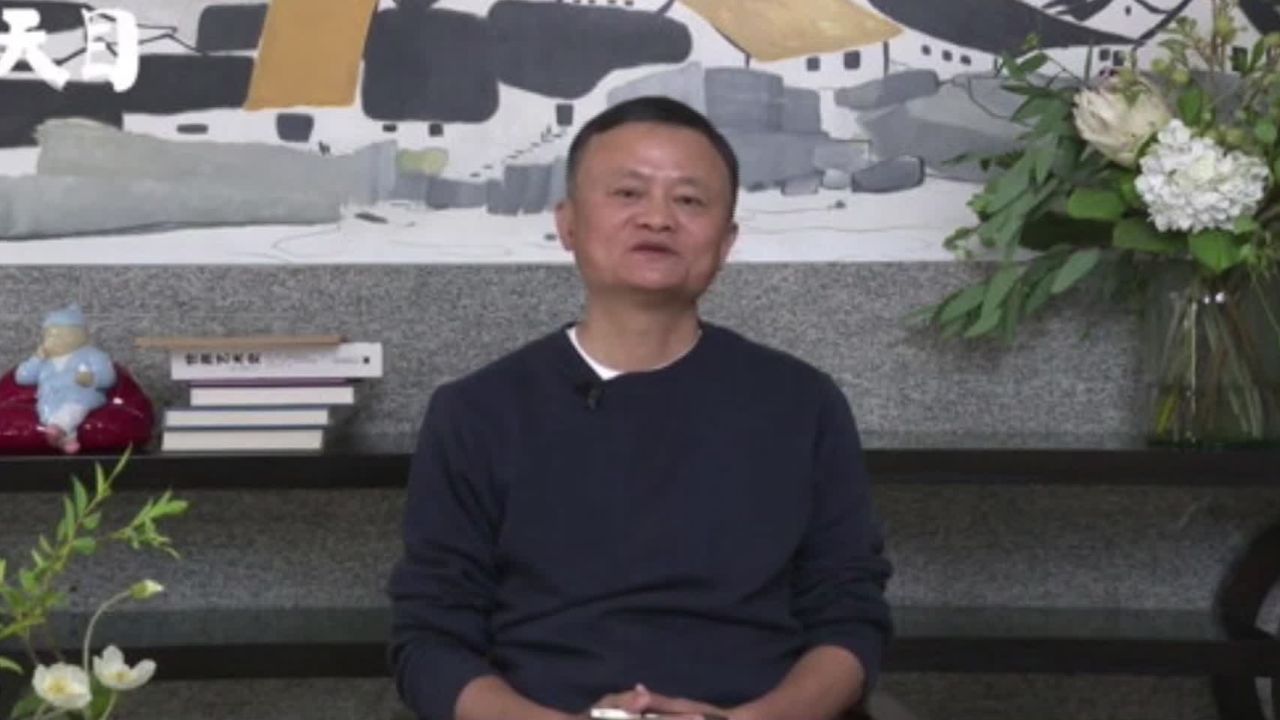

This is exactly the kind of pressure that Ma, the co-founder of Ant and Alibaba, was worried about when he landed himself in hot water with regulators late last year.

“The Basel Accord is more like a club for the elderly,” Ma said during a speech in Shanghai last October, his last before Ant’s IPO was pulled and he largely retreated from public life.

“What it wants to solve is the problem of the aging financial system that has been in operation for decades,” Ma said. But while systems like Europe’s are complex, he called China’s financial system an “adolescent” that is better served by innovative tech firms that can bring banking to poor populations and small-time businesses that are otherwise locked out of traditional banks.

“The Basel Accord is about risk control,” Ma added. “But China’s problem is the opposite. China doesn’t have systemic financial risks, because it basically has no financial system.”

The tech entrepreneur’s choice of words during that speech grew even more colorful — he criticized China’s conventional, state-controlled banks for having a “pawn shop” mentality — and likely spurred Beijing to act swiftly in retaliation.

While the Shanghai Stock Exchange was cryptic at the time about the reason for pulling the IPO, saying that Ant’s listing had “major issues,” the government’s response since indicates that its decision was about exercising authority and control.

“China’s central planners’ primary concern is that the party remains in control of all aspects the economy and business sector,” said Alex Capri, a research fellow at Hinrich Foundation and a visiting senior fellow at National University of Singapore. “The rapid growth of Chinese tech giants clearly diminishes the influence of state-owned banks and [other] financial institutions, and that diminishes the power of the Communist Party.”

China’s tricky balancing act

Beijing’s calculated crackdown on tech is rooted in economic concern just as much as exercising control.

Authorities have long been incredibly wary about whether the influence that tech firms have over the financial sector makes that industry vulnerable to structural risks. If any of the major players failed for some reason, that could wreak havoc on China’s economy.

“The idea is to have these firms more firmly under Beijing’s control so that they can better serve the state when it comes to building the next generation of [the Internet of Things] or financial infrastructure or rolling out the digital [yuan],” Capri said. “All of these actions promote and project Beijing’s power.”

But it’s also a tricky balancing act. While Chinese President Xi Jinping has long favored state-owned firms over private ones like Alibaba and Ant, analysts point out that those state companies are not nearly as adept at driving productivity and innovation as their publicly owned counterparts.

“There are legitimate concerns about financial risks and anti-competitive behavior that justify greater oversight of the tech giants,” wrote Julian Evans-Pritchard, senior China economist at Capital Economics, in a research note last week. “But we think a desire to reassert control means that regulators are now swinging too far in the other direction. This threatens to undermine the recent prop to economic growth from rapid productivity gains in the tech sector.”

That means Beijing will likely remain careful “not to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs,”said Martin Chorzempa, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, who researches financial tech innovation in China.

“There is widespread recognition of the importance of the super apps for China’s innovation ecosystem, hopes for international influence and status, and its economy,” he added.

Fuller of the City University of Hong Kong agreed. If China wants to compete with the West, he said, the country “has to pursue industrial and technology policies in a more efficient manner.”

There is “a trade-off between promoting state ownership and innovation,” he added.