On January 5, as results came in from the Senate runoff election in Georgia, the texts between President-elect Joe Biden’s senior staff went late into the night and into the next morning. With the Senate majority on the line, and full control of Washington in their grasp, the outcome of the two Georgia races would determine the fate of what they all agreed was their top priority for the new administration — passing a massive Covid relief package in the opening weeks.

They’d been working on it for nearly two months, identifying needs and, at Biden’s direction, crafting the plan around them, regardless of cost. But if the Democrats won in Georgia, the plan would suddenly go from an aspiration they would have to bargain with Republicans over, to a reality as long as they kept their party unified.

With no war room to report to that night, no headquarters or even a transition office to gather in, the Biden staffers were all glued to the TVs in their homes around Washington, or, in the case of incoming White House chief of staff Ron Klain, in Delaware with Biden, firing off texts to one another as each Georgia county reported results.

“Everybody understood for weeks what the impact of winning the two Georgia races might be,” Steve Ricchetti, the long-time Biden adviser who would become counselor to the president, told CNN in an interview. “We invested a lot of time and effort in it in the weeks leading up to it because we obviously understood what it could mean for our agenda.”

By late morning the next day, it was clear that Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock had done the improbable, sweeping both races in Georgia and delivering the Senate back to the Democrats less than a month before Biden took office.

The twin victories marked a political earthquake for the incoming president and opened the door to one of the largest public health and economic relief proposals in US history.

For all of Biden’s talk of bipartisanship, Democrats now had the power to move their top priority without a single Republican vote. It was the same situation as 2009, when the Obama administration rushed to pass a relief package during his first month in office. Back then Democrats lowered the size of the plan to garner some Republican support, a decision many of them came to regret during the slow recovery that followed.

This time would be different. From the outset, the common goal among Biden’s team was to go big – even if that meant going it alone.

At $1.9 trillion, the American Rescue Plan is second only in size to last year’s $2.2 trillion CARES Act. When it was first unveiled to the public on January 14, the assumption among Republicans and even some Democrats was that Biden’s nearly $2 trillion moonshot was an opening offer, a place to start negotiations that would inevitably lead to a smaller price tag.

But there would be no negotiating from Biden’s team. That was the number, and while there was room to bargain over marginal side items, the topline wasn’t moving.

This story is based on interviews with more than two dozen officials from the White House, Capitol Hill and outside interest groups who worked directly with the campaign and transition on Biden’s cornerstone legislative proposal. CNN also spoke to Republican lawmakers and aides who remain agog at the size of the package and the speed with which Biden has pushed it along.

Last week, as Democrats on Capitol Hill began the legislative maneuvering to prepare the bill for reconciliation, a few key Republican senators remained convinced that Biden is in a different place than his more progressive – and aggressive – staff. Other Republican senators have expressed borderline shock at their former colleague’s firm line.

Even Larry Summers, long considered one of the pre-eminent economists in the Democratic Party – though he is loathed by many on the left – warned the plan would spend too much money too fast and crowd out future funds for other progressive priorities like infrastructure, education and climate.

Yet the Biden team has remained unfazed, and congressional and White House officials are targeting early March for the bill to land on Biden’s desk, which would mark it as the largest piece of spending any president has enacted in his first 100 days. Bipartisan Senate talks are still ongoing, aides say. But with Democratic leaders in both chambers aligned with the White House, there’s little sense at this point they will change the direction of things.

There are certainly risks involved. Republicans have lashed out at Biden, claiming his calls for unity and bipartisanship must not be genuine. The economic concerns raised by Summers and Republicans will trail the proposal through every turn of the months and years ahead. The huge bill also threatens to put moderate Democrats in a difficult spot, and Biden can’t afford to lose a single one.

With the Senate deadlocked 50-50, the bill passed its first test last week thanks only to the tie-breaker vote of Vice President Kamala Harris, when Democrats muscled through their budget resolution. Though the party has stayed unified in the opening weeks, a single senator can slow or halt the process altogether.

Sen. Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, kept the process on track – and elicited sighs of relief among Democrats – when he said he’d vote to move forward in a statement shortly before the vote. But it included a warning for the sweeping package.

“Let me be clear – and these are words I shared with President Biden – our focus must be targeted on the COVID-19 crisis and Americans who have been most impacted by this pandemic,” Manchin said.

But that high wire act has done nothing to convince Biden and his team to scale back.

“The way I see it, the biggest risk is not going too big,” Biden said in a sweeping economic speech February 5 outlining his hardline on the proposal. “It’s if we go too small.”

Building the bill

The meetings began in November, not long after the election was called for Biden. Even before the President-elect’s transition officially kicked into gear, Biden’s top advisers, many of whom would get jobs in the White House, gathered daily – and always virtually – to hash out what they knew would become the single most prominent marker of their accomplishments in their first 100 days in office.

From the start, they took a unique approach.

Often, when spending bills are crafted, the topline number is settled on first as lawmakers and officials figure out what is possible and work down from there. But Biden’s team says it started at the bottom and built up. The $1.9 trillion figure wasn’t nailed down until the days before its public release, advisers say.

As they went, the goal was two-fold – fund everything needed to end the pandemic, while also doling out enough money to float struggling Americans until things got back to normal. The proposal includes $160 billion for vaccine distribution and testing, $130 billion for K-12 schools, and $350 billion for state and local governments. It also contains hundreds of billions more in aid to families, including $1,400 in direct monthly payments, expanded nutrition assistance programs, extensions of emergency unemployment programs, and big expansions of the Child Tax and Earned income Tax Credits, boosting the benefits to a level some economists project could cut child poverty in half.

As the plan came together, administration officials said one priority remained clear: Biden didn’t want just a short-term infusion of stimulus, with patches and temporary extensions to various aid provisions to keep the economy afloat for a few months – he wanted to lock in long-term aid and investment. Enough money not just to pull the US out of the pandemic, but to give it the fuel for a massive future expansion.

It marked a fundamentally different approach from congressional Republicans – one that would define negotiations destined for failure. Senate Republicans viewed tens of billions in unspent funds from past relief packages and an economic picture that showed signs of recovery once vaccines were deployed as a reason to carefully target any new aid.

Republicans would offer shorter-term extensions of individual benefits, smaller direct payments, no money for state and local governments, all with a significant influx of funds for vaccine distribution and testing. It would be rejected out of hand.

To build the proposal and help shepherd it through, Biden fielded a familiar group of advisers, the most senior of whom had all served in key roles in the Obama White House. The group eventually included more than a dozen officials. Jeff Zients became Biden’s coronavirus response coordinator, Cecilia Rouse was nominated to chair the Council of Economic Advisers, and Susan Rice was appointed to lead the Domestic Policy Council.

Brian Deese, the incoming director of Biden’s National Economic Council, became Biden’s point person on selling the package. Deese, who was running the automotive industry rescue for Obama in 2009 even as he was finishing his Yale law degree, held meetings and calls with dozens of lawmakers from both parties. Deese kept outside supporters looped in, and served, in large part, as the face of the proposal in the media.

He also became a point of frustration for Republican lawmakers, who quickly came to view him as unbending in any talks over the plan, GOP aides told CNN. That is less a reflection of Deese, administration officials say, and more a reflection of how the package was constructed from the start.

Shortly before Christmas, Biden’s team got an unexpected assist when President Donald Trump began threatening to sink a bipartisan relief package if its direct payments to Americans weren’t increased to $2,000, from $600. Up until then, direct payments weren’t a focus of what Biden’s team was putting together. But congressional Democrats seized on the moment and passed the increase in a House bill that surprisingly secured 44 Republican votes.

Though the increase was halted by the Republican-led Senate, the House vote proved there was bi-partisan support for giving significantly more money to families. Biden quickly went on the record in support of the idea, and it soon became a focal point of the two Georgia Senate runoffs, with Warnock and Ossoff pledging to get the increase passed if elected.

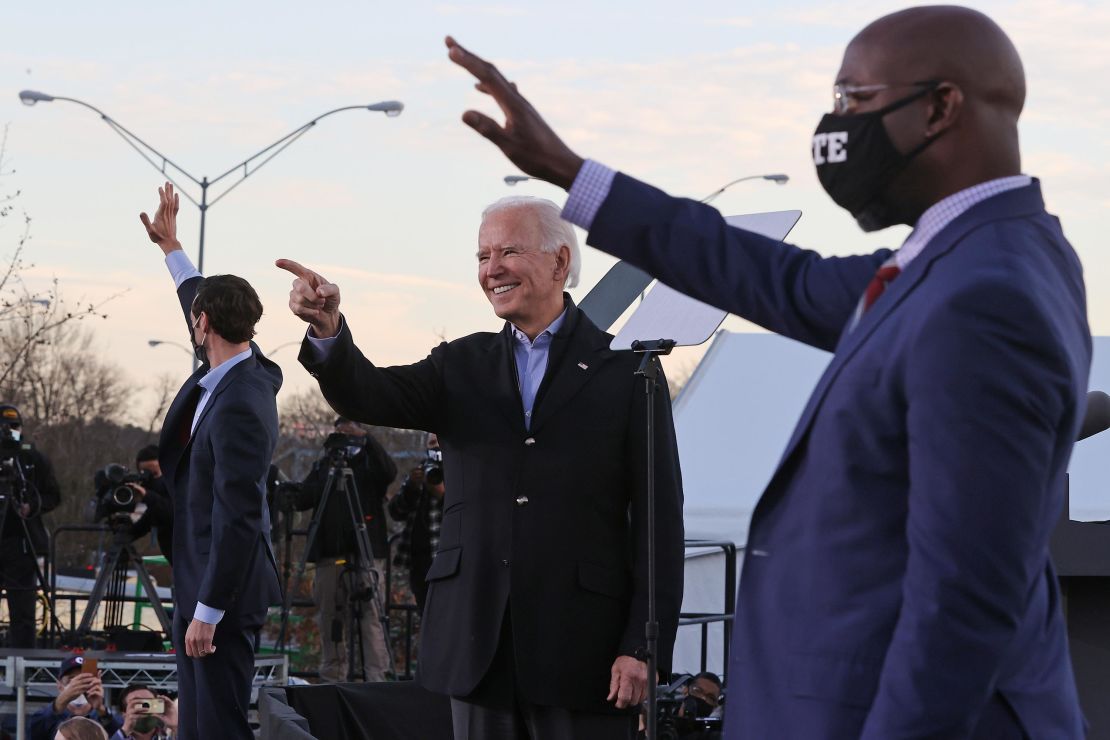

“If you send Jon and the Reverend to Washington, those $2,000 checks will go out the door,” Biden said during a campaign stop in Atlanta the day before the runoff election.

After Warnock and Ossoff both won, Biden’s team made those checks – an additional $1,400 to the $600 already disbursed – a central selling-point for the proposal. Biden, as the proposal started to move through Congress, repeatedly told lawmakers backing off the size of the checks was a promise he simply wouldn’t break. It also meant the size of the package would get even bigger.

Problems with vaccines

As meetings stretched past the holidays and into the new year, a troubling picture began to emerge within Biden’s team over the state of vaccine distribution they’d be inheriting. Data coming in from transition landing teams at agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Health and Human Services, as well as intelligence from companies contracted to create and distribute the vaccine, suggested something worse than they had expected.

Not only was the economy in a deep hole, the thing that would help the most, a robust plan to get vaccines into the arms of millions of Americans, was almost non-existent, advisers say.

While the Trump administration’s work to produce a vaccine was unprecedented in its speed and success, its plan for how to distribute the shots themselves – heavily reliant on states, limited in centralized data and lacking a fulsome infrastructure – was anything but.

Vaccine distribution “was much more troubled than we thought it was,” a senior administration official said.

The more they learned, the more Biden’s team came to the view that vaccine distribution under the Trump administration “wasn’t even at the starting line,” one person in close contact with Biden’s team said. The view was “we have to rebuild just to get to that starting line,” the person recounted.

As they calculated what would eventually be the $160 billion vaccine and testing piece of the proposal, Biden’s team built itself a cushion as they modeled out various scenarios of how the months ahead would play out, deciding to overshoot projected needs rather than risk coming up short.

“They were walking a pretty fine line between being able to outright justify it while also making sure it was going to be enough regardless of what came next” in the crisis, another person involved said.

As the administration pushed toward Biden’s stated goal of 100 million vaccinations in his first 100 days, the vaccine and testing elements of the proposal became the least controversial.

“We went in thinking these were negotiations”

On January 27, nearly two weeks after the Biden team first unveiled the $1.9 trillion price tag, Senate Republicans held an internal conference call to talk strategy. By then, it was apparent they wouldn’t be playing much of a role in crafting the bill. According to two people on the call, several moderate senators teed off on what they viewed as clear signals that Biden’s team had no intention of negotiating.

Sen. Rob Portman, an Ohio Republican, pointed out that none of the Republicans were consulted as the administration crafted its $1.9 trillion plan. Portman, who would later speak with Biden by phone, told his colleagues the entire process up to that point painted Biden’s message of bipartisanship as a façade.

Sen. Susan Collins, who would serve as the leader of the 10 Republicans seeking talks with Biden told her colleagues she felt the same way. Collins and Biden had a close working relationship, one that played a role in her vote in favor of Obama’s stimulus when Biden was vice president. But Collins, the people said, told her colleagues that interactions with White House staff up to that point led her to believe the White House was in a “take it or leave” situation. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, an Alaska Republican, echoed similar sentiments.

While nobody took direct umbrage with Biden himself, frustration with his team was pervasive.

A group of 10 Republican senators led by Collins, Murkowski and Portman grappled with how to proceed. In a deliberate effort to signal that they were serious about dealing with the pandemic, the group released a $618 billion counter proposal that made a point of matching to the dollar the White House’s funding request for vaccine distribution and testing, $160 billion.

The hope was to show good faith and open negotiations on other items. Instead, Republicans ran into what one senator told CNN was “a total wall.”

“We went in thinking these were negotiations,” a senior GOP aide told CNN. “They went in saying this is our proposal if you’d like to join us.”

It’s a reality Republicans say runs completely contrary to Biden’s stated goal of bipartisanship. More than one GOP lawmaker has said publicly they believe the unwillingness to negotiate came more from Biden’s advisers than Biden himself.

To many Republican senators, that sentiment was bolstered by what happened on February 1 after a nearly two-hour Oval Office meeting with Biden and his top advisers. According to participants on both sides, the sit-down was overwhelmingly positive. After four years of dealing with President Donald Trump, to Republicans in the room, the meeting was a refreshing change. Even if he was a Democrat, Biden engaged on legislative details in a way that Trump rarely had.

Collins and her Republican colleagues left optimistic they had created an opening to negotiate on a few items.

“I think it was an excellent meeting and we’re very appreciative that as his first official meeting in the Oval Office, the President chose to spend so much time with us in a frank and very useful discussion,” Collins told reporters just outside the West Wing.

But a little more than an hour later, the White House released a statement sinking any hopes of significant Republican deal-making. The tone – firm, and line after line underscoring the view the White House wasn’t budging – blindsided the Republicans who participated, multiple sources said.

Republicans told their colleagues after the meeting the interactions with Biden made them believe he was open to tangible negotiations, with a willingness to listen, take notes, consult his own briefing book, and engage on each topic, sources told CNN. He didn’t offer any concrete concessions, but he had made clear talks should continue – and that his staff would follow up with more detailed justifications for his plan.

Plowing ahead

By 11 a.m. the next morning, White House officials sent memos to the GOP senators laying out some key justifications for their plan, most notably on direct payments and school funding.

The memos, obtained by CNN, demonstrate no hint of malleability. Instead, they underscore just how far about apart both sides were.

While Republicans were proposing $20 billion in K-12 school funding, the White House wasn’t budging off its desire to spend more than six times that. In justifying its $130 billion request for schools, which includes money not just for the current school year, but the next one as well, the White House said it intended to give school districts “financial certainty that they will not have to lay off teachers next fall in order to implement consistent COVID-19 safety protocols.”

Republican critics remain stunned by the amount of money the White House wants for schools, especially since so much of what’s already been passed from earlier coronavirus relief packages remains unspent. Of the $67.5 billion in school funds that Congress has appropriated since last year, only $4.4 billion had been spent as of January 22, according to spending reports shared with lawmakers.

White House officials say they believe that money, which has already been obligated, will be spent in the weeks ahead.

“This isn’t finished,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said last week of the pandemic. “But experts agree that remaining damage to our economy does not require another multi-trillion dollar non-targeted band-aid.”

Republicans didn’t respond to the White House memo for more than two days – something Biden aides viewed caustically – and when they did, their letter outlined the same concerns about key elements of the proposal, and the data used to justify the White House numbers, raised in the Oval Office. It provided yet another window into talks that appeared to be going nowhere fast.

By Thursday, February 4, Democrats in both chambers were on track to have the first key legislative step – passing budget resolutions – done before the weekend.

That afternoon, the Washington Post published a column from Summers warning that the Biden plan was, in fact, too large for the moment and risked overheating the economy.

White House aides were furious at Summers, particularly over his timing. The next day, Biden would give a major economic speech designed to lay out his rationale for the size, scale and speed of the package. The column created one of the first messaging headaches for the new administration. It also outraged the economic team because they viewed it, in the words of Biden CEA member Jared Bernstein as “just wrong.”

“This isn’t stimulus and for some reason Larry thinks it’s stimulus,” one source involved in the process, who pointedly noted Biden’s teams had “obviously” considered the concerns outlined by Summers, told CNN. “This is a bridge and this is investment, one that will disburse in various stages over several quarters.”

Emboldened, that afternoon the Senate began a 15-hour marathon voting session, with all 50 Senate Democrats signing onto a budget resolution that would lay the groundwork for the eventual package. The final vote came before dawn the next morning, when Harris served as the tie breaker. A few moments later, at 5:35 am on February 5, newly-minted Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, standing on the Senate floor, affixed a microphone to his jacket lapel. It had been one month since Ossoff and Warnock, now US Senators, had made possible what they’d just done.

Schumer noted the anniversary. Then he underscored the moment.

“Just a month from that day, we have taken a giant step to begin to fulfill our promise.”