The early lines of division between the parties during Joe Biden’s presidency point toward rising confrontation, sooner rather than later, over rules and traditions in the Senate that empower the minority party to block the majority.

The quick turn by Biden and congressional Democrats toward reliance on the special “reconciliation” procedure for passing their Covid-19 “rescue” package with only 51 Senate votes underscores their conviction that in today’s highly polarized environment, they are unlikely to secure support for anything close to their plan from 10 Senate Republicans, the number they would need to break a GOP filibuster.

Yet by relying on the reconciliation process to pass that priority, Democrats may only raise more questions about whether they should sustain other venerable Senate procedures – including the filibuster and deference to home state senators on judicial nominations – that impede majority rule and provide the minority a virtual veto on many fronts.

Though the Senate has trimmed back rules that empower the minority party to block the majority, it has not completely eliminated procedures such as the filibuster, which requires 60 votes to pass most legislation, or the “blue slip” system that has allowed senators from the opposite party to veto judicial nominations in their home states.

Over the next two years those Senate procedures enabling minority rule are likely to face more pressure than ever, as Democrats and their allied interest groups face the prospect of Republicans using them to slow or derail any of their plans that can’t be shoehorned into the complex reconciliation process, from a new Voting Rights Act to citizenship for the “Dreamers” brought to the country illegally by their parents to a $15 federal minimum wage, which Biden acknowledged to CBS this weekend probably won’t pass muster under the reconciliation process.

As the parties joust over those ideas in the coming months, the Senate procedures frustrating majority rule may become even more controversial because the chamber’s basic structure, which provides each state two senators regardless of population, now creates such dramatic partisan distortions: Though each party holds 50 Senate seats, the GOP’s reliance on smaller, preponderantly White and heavily rural interior states means that if you assign half of each state’s population to each senator, Democrats represent nearly 42 million more Americans than Senate Republicans.

Senate rules that provide an effective veto to a legislative minority would face growing pressure under any circumstances; but when that veto is exercised on behalf of such a distinct minority of the population, the pressure is certain to grow only more intense.

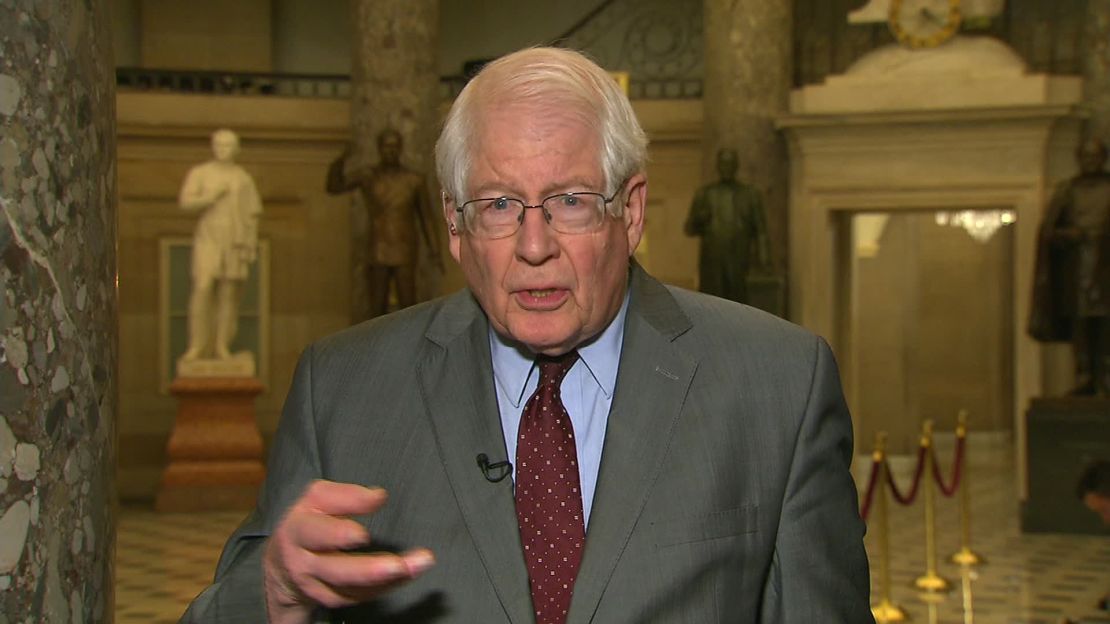

While the “convoluted reconciliation process” offers a temporary “workaround” to the problem of minority rule in the Senate, “that’s a very limited answer,” says Democratic Rep. David Price of North Carolina, who’s also a political scientist and recently published an updated edition of his book “The Congressional Experience: An Institution Transformed.” Before long, Price says, Democrats will have to confront head on the underlying question of whether in this highly polarized era they can maintain the Senate procedures, like the filibuster, that allow the minority to block the majority’s program.

If Democratic priorities that pass the House die in the Senate because of Republican filibusters, Price predicts, “the pressures just become very intense for some kind of alteration of the Senate rules. … I just think the notion that every bill, everything from gun control to Dreamers, will be subject to filibuster becomes just intolerable at that point.”

History of Congress’ majority-minority power

The filibuster, in fact, more and more resembles a vestige of an earlier era, as Congress transforms into something like the kind of parliamentary system used abroad in such nations as the United Kingdom or Germany, in which the majority party controls the agenda, the minority party opposes it and both dissension within the parties and cooperation between them are rare. The filibuster, and other Senate rules favoring the minority, creates a contradictory dynamic, a parliamentary system where the majority cannot rule.

“If you have a minority party that will not cooperate, and if you have a Senate that has the rules that it does, then you are going to end up with the inability to focus on the major issues that face the society,” says Norm Ornstein, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute who’s a co-author of “It’s Even Worse Than It Looks,” a 2012 book about congressional dysfunction.

Concern about the congressional rules that allow minorities to block action – what political scientists call the system’s “anti-majoritarian” tendencies – was common in the first decades after World War II. In those years, both parties were riven by ideological divides that separated liberal Northern Democrats from deeply conservative Southern Democrats and moderate-to-liberal coastal Republicans from staunchly conservative Midwestern ones.

In that era of “four-party politics,” as it was known, the informal alliance of Southern Democrats and Midwestern Republicans – a “conservative coalition” symbolized by segregationist Democratic Sen. Richard Russell of Georgia and isolationist Republican Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio – often held a veto over legislative action, no matter which party controlled the White House or Senate majority.

In a landmark 1950 report, the American Political Science Association called for restructuring congressional rules to allow the majority party more leverage to implement its agenda. That process began in the 1960s. In a key early step, House Democrats enlarged membership in the chamber’s Rules Committee to ease the hammerlock that the conservative coalition, led by longtime Chairman “Judge” Howard W. Smith, a Virginia Democrat, exercised there over President John F. Kennedy’s agenda. In the 1970s, liberal Democratic reformers led by the late Rep. Richard Bolling of Missouri finally overthrew the seniority system that allowed conservative Southerners to control key committees while opposing most of the party’s agenda and instead empowered the party caucus to elect committee chairs, which incentivized more party loyalty.

When Republicans gained the House majority after 1994, they employed these powers more aggressively than Democrats ever did and took other steps to centralize power over legislative action in each chamber’s leadership. Georgia’s Newt Gingrich, the House GOP speaker in the 1990s, probably more than any other individual envisioned Congress’ transition to a more parliamentary-like system defined by greater unity within the parties and relentless conflict between them. But when Democrats regained the House majority after 2006 and again after 2018, they largely maintained the Gingrich changes that centralized control and encouraged majority rule.

“The march has been pretty steady toward more polarized parties, which is to say homogenous within and distanced from each other, and a more centralized institution,” says Price.

The Senate’s trajectory, though, has been more uneven. During the 1970s, the parties also ended reliance on seniority for naming Senate committee chairs – though they have exercised that power more rarely than in the House. And during the 1970s, senators lowered the threshold for breaking a filibuster from 67 votes to 60, theoretically a step toward majority rule. The offsetting factor was that after the 1970s the use of the filibuster steadily became more routine – with Republicans in particular creating a 60-vote threshold for almost anything Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and especially Barack Obama sought to pass.

In response to systematic GOP filibusters of Obama’s choices for the federal appellate courts, Senate Democrats in 2013 ended the filibuster for judicial nominees below the Supreme Court and executive branch appointments; Senate Republicans, after Donald Trump became President, then ended the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees. But it remains in place for general legislation, which has encouraged both parties since President Ronald Reagan’s day to use the budget “reconciliation” process as a means of passing key elements of their agendas through a simple majority vote.

The ‘blue slip’ system for judges

With much less attention, the tradition of deference to home state senators on judicial appointments has also empowered the minority. Under the so-called blue slip system, presidents historically have consulted with senators on federal district and appellate court nominees in their geographic areas. Chris Kang, a former Senate aide and deputy White House counsel for Obama who handled judicial appointments, notes that the blue slip system dates back to 1917 but assumed its present character during the civil rights era.

At that point, he says, segregationist Southerners like Mississippi’s fearsome Democratic Sen. James Eastland used the system to veto the appointments of judges they considered too liberal on civil rights. “He changed the principle from consultation to an outright veto,” says Kang, co-founder of the advocacy group Demand Justice, which argues for judicial revisions. “That’s what changed the complexion of how blue slips were actually used. “

Under President George W. Bush, Senate Republicans eliminated the blue slip tradition for the more powerful appellate court nominations, stripping the minority Democrats of their ability to block choices on those grounds. (Republicans maintained the system for lower-level district nominees). When Democrats regained the majority after 2008, they restored the blue slip system, only to see Senate Republicans aggressively employ it to impede Obama’s nominations.

“In the Obama administration, notwithstanding the history, we sought to find consensus,” says Kang. “And you see a number of Obama nominees were blocked because Republicans could wield that veto. All but one [blocked] were women or people of color.”

Predictably, Senate Republicans once again eliminated the blue slip system for appellate court nominees after Trump won – and, in their drive to fill the courts with conservative appointees, repeatedly nominated and confirmed judges opposed by their home state Democrats. Now it’s unclear whether Democrats will again restore the blue slip veto for appellate judges or maintain it for district judges. Fear that Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California would do so out of respect for Senate traditions was one reason for the intense liberal opposition to her becoming chair of the Judiciary Committee; Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois, who eventually won the post, has hinted he will not restore the system at least for appellate court nominees, but has not firmly committed.

Kang, like many activists, says the time has come to eliminate the tradition for all judicial nominees, especially after so many Senate Republicans joined in Trump’s efforts to overthrow the 2020 election. “Why should Ted Cruz get to choose the district court [nominees] in Texas: Why should he have a veto?” Kang asks pointedly. “Why should Josh Hawley have a veto [in Missouri]? There is no question about their intentions now, following January 6: Why should they have a veto? Why should we leave these seats open? There is just no reason.”

Busting the filibuster?

The blue slip battle is likely only a prelude to the marquee procedural question of the next two years: whether Democrats eliminate the filibuster for all or some legislation. The party can change the filibuster rules with a simple majority vote, but today at least two centrist Democratic senators – West Virginia’s Joe Manchin and Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema – have indicated they oppose any change.

The question is whether that opposition can stand for two years if a procession of Democratic priorities pass the House and then are killed, one by one, by Republican filibusters in the Senate. Tom Daschle, the former Democratic Senate majority leader from South Dakota, is one who thinks the answer is no.

“I don’t think so,” he told me when I asked if the filibuster could survive through this entire legislative session. “I don’t think production can be held hostage to process,” he added. “I think what the American people want is production. They want to see something affect them in a meaningful and palpable way. … There is just no way [to say], ‘I can’t deliver that production because I am going to respect these processes.’ I don’t know how willing people are going to be to accept that.”

Price, Daschle and many others believe the issue could come to a head over the Democratic agenda to protect and expand voting rights. The House is nearly certain to pass a new Voting Rights Act and HR 1, an omnibus election bill that requires all states to offer on-demand mail and early voting as well as same-day and automatic voter registration and combats gerrymandering by requiring states to use independent commissions to draw congressional districts. In the last Congress, both bills passed the House without a single dissenting Democratic vote, and every Senate Democrat likewise co-sponsored each of them. But both face the likelihood, under the current rules, of dying beneath filibusters conducted by Republican senators who almost all rely preponderantly on White votes to win election.

After African American voters played such a central role in delivering Democrats control of Congress and the White House, many observers think it will be nearly impossible for Democratic leaders, in effect, to tell the Black community that it was more important to preserve the filibuster than to pass these bills safeguarding their voting rights.

In a typical comment, Nsé Ufot, executive director of the New Georgia Project, a Stacey Abrams-affiliated group critical to the party’s Senate wins in the state, told me recently that it would be “catastrophic” if Democrats “can’t make progress” on the agenda they promised voters, “because of existing rules that they have the ability to change.”

Daschle agrees that a Republican filibuster of a new Voting Rights Act – which is designed to reverse the 2013 Shelby County decision by five GOP-appointed Supreme Court justices to severely weaken the law – might be the trigger that forces Democrats to act, especially after Obama recently described the filibuster as a “Jim Crow relic.”

“By far it carries the greatest emotion, the greatest history,” Daschle says. “Even Barack Obama mentioned that was used effectively by those opposed to the civil rights legislation in the ’50s and ‘60s. This is just an extension of that historical fact. These days, it would be incredible if we weren’t able to address that legislation. It is essential that it get done. And it may be [ending the filibuster] is the only way that you get it done.”

Oregon’s Democratic Sen. Jeff Merkley, the chief sponsor of the Senate equivalent to HR 1, has suggested that even if all 50 Democrats are unwilling to end the filibuster for all legislation, they might agree to revise it just for bills setting the rules for elections.

The irony is that voters appear far ahead of the legislators in treating Congress as a parliamentary institution. More and more of them appear to be casting their ballots based on judgments about which party they want to control Congress rather than personal comparisons of the candidates. Split-ticket voting, in which voters support presidential candidates of one party and congressional candidates from the other, has virtually disappeared.

As recently as the 1970s and 1980s, Democratic senators still held about half the seats in the states that twice voted for Republican Presidents Richard Nixon (32 states) and Ronald Reagan (44 states); now each party holds just three of the 50 Senate seats in the 25 states that supported the other party’s presidential candidate in November. (When Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine triumphed last November, she became the only senator in either 2016 or 2020 who won in a state that supported the other party’s presidential candidate.)

Likewise, just nine House Republicans and seven House Democrats hold districts that supported the other party’s presidential candidate, according to recent calculations by political analyst J. Miles Coleman; during the three presidential elections of the 1980s, there was an average of 160 such split-ticket districts, 10 times as many.

In this increasingly parliamentary political system centered on majority rule, the Senate now stands out even more conspicuously as the choke point that allows a minority to shape, and even control, the national agenda. The fact that the Republican Senate minority also represents such a distinct minority of the population (only about 44%) only adds to the pressure for change. So do the torrent of at least 165 laws that Republicans, citing Trump’s discredited claims of voter fraud, are proposing to make it tougher to vote in states from Arizona to Georgia and the prospect of severe partisan gerrymanders to benefit the GOP in many of those same states.

Such gerrymanders and obstacles to voting would make it easier for Republicans to maintain power in Washington even if Democrats win support from more voters, as they have in seven of the past eight presidential elections, an unprecedented streak. Democrats face an uphill legislative battle in stopping either gerrymanders or new voting barriers in red states now dominated by Republicans, and the six GOP-appointed Supreme Court justices are unlikely to constrain such actions either, most legal experts agree.

Passing national election standards through HR 1 and a new Voting Rights Act represents the Democrats’ best chance to preempt these Republican efforts to entrench their political power, but Democrats can pass those measures only if they roll back or eliminate the filibuster. In other words, restoring majority rule to the Senate may be the key to protecting majority rule in the country overall.

“If Democrats don’t get an HR 1 or some variation of it through,” says Ornstein, “we are going to end up with more and more crises of legitimacy and more and more [cases of] extreme minority rule.”