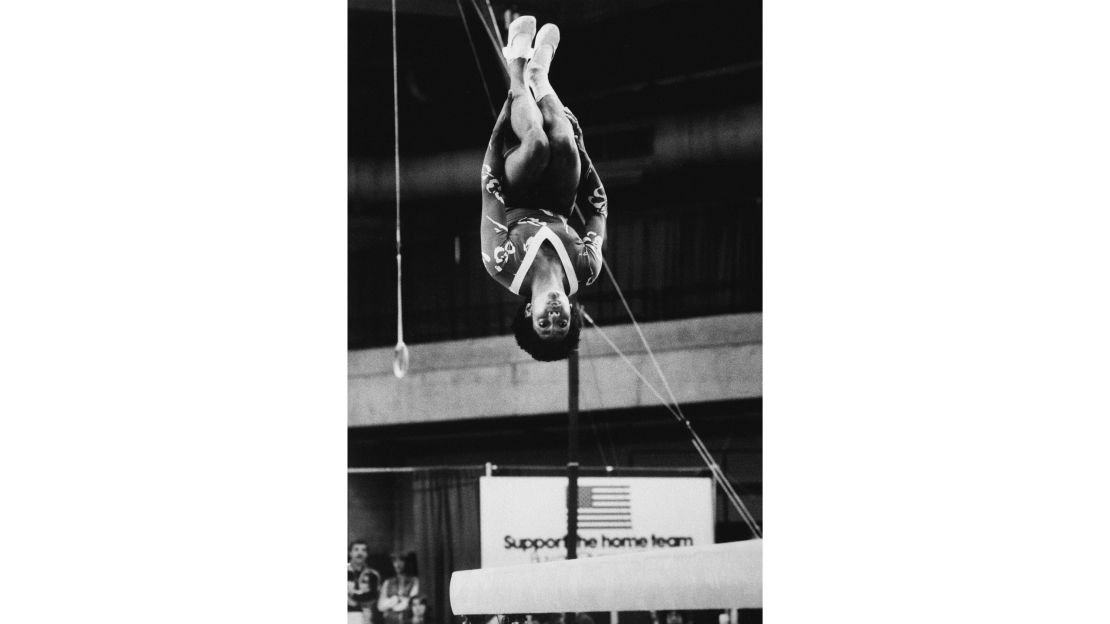

At just 14 years old, Dianne Durham stood before thousands of spectators on the biggest stage in American gymnastics.

She’d just hurt her foot in an earlier, near-perfect balance beam routine – but she wasn’t thinking about the pain, she told a CBS reporter. She’d been “having too much fun to let it bother” her, she said.

She didn’t let the pressure of being one of the only Black competitors at the 1983 Gymnastics Championships of the USA bother her either – she was poised to become its first Black champion.

Dressed in a purple patterned leotard, Durham paused on the mat, took a deep breath – and then she leapt.

In under two minutes, she breezed through an effortless floor routine, soaring through the air with the grace of a trained dancer and the strength of someone much older. Finishing with a double twist, she landed with her arms raised in victory.

The crowd roared. Fans holding a large banner that read “We love Dianne” rose to their feet.

Durham’s overall performance earned her four gold medals and the distinction of being the first Black gymnast to become the US all-around champion.

That remarkable performance is rarely mentioned among the seminal moments of US women’s gymnastics. But her career, however brief, still set a precedent for the Black gymnasts and Olympians who would follow.

Durham, who went on to become a gymnastics coach, died Thursday, USA Gymnastics confirmed. Her husband, Tom Drahozal, told CNN that the 52-year-old died after a short illness.

“Her personality was bubbly and she was a very charismatic individual who was respected and admired by a lot of people,” Drahozal said. “Whether highest level or recreation class, all the students admired her because she treated them all the same.”

From national champion to retiree

A native of Gary, Indiana, Durham moved to Houston, Texas, as a teen to train with gymnastics coach Béla Károlyi at the Károlyi Ranch (now infamous for being one of the sites where former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar sexually abused young girls, decades after Durham’s stint there).

At the ranch, she trained alongside future greats, including Mary Lou Retton, who told CBS Sports in a 1983 interview that though the two were friends, Durham was her “best competition.”

Durham bested Retton at the 1983 championship with her immaculate performance. Károlyi embraced her afterward as national TV cameras focused on her surprised, ecstatic reaction.

Her appearance at the championships should’ve been the start to a storied career that would put her along the likes of Retton and other gymnasts from that era, when women gymnasts in the US started to become international stars and Olympians.

But Durham’s Olympic dreams ended with an ankle injury in the trials for the 1984 Olympics. She believed Károlyi would petition to include her in the training group since she couldn’t finish the trials, she told ESPN in a 2020 interview, but since she was kept from competing in the world championships that year, she was disqualified from the Olympics.

“The city of Gary was behind me 100,000%, and I felt like I let my family down,” she told ESPN. “Everybody uprooted their lives for me.”

Retton made the Olympic team and won gold. Durham, still a teen, retired from the sport in 1985.

Her career set a standard for Black gymnasts

Black women and girls would go on to become Olympic gymnasts, including Dominique Dawes, who in 1996 became the first Black gymnast to win an individual event at the Olympics. In 2012, Gabby Douglas became the first Black gymnast to become the Olympics’ all-around champion. And since her debut in 2016, Simone Biles has been hailed as the best gymnast the sport’s ever seen.

The three women who succeeded Durham tumbled and twirled and broke records while overcoming racial bias and prejudice in a sport previously dominated by White women. That much hasn’t changed in the almost 40 years since she competed, Durham wrote on Facebook.

“In my own life and gymnastics career I encountered discrimination and prejudice,” she wrote on Facebook in June, days after George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police. “It didn’t stop me from reaching all of my goals, but it did play a role in preventing me from reaching some of my biggest goals.”

But when she was competing as a teen, she said, she never once thought about the history she could make as the first Black national champion.

“Do you know how many people had to tell me that?” she told ESPN. “I could not understand why that was such a humongous deal.”

It took time for Durham to absorb the weight of her achievements – something that wasn’t easy to do, considering how quickly she was shunned from the spotlight.

But she continued to work in gymnastics, eventually coaching, judging and running her own gym, Skyline Gymnastics, in Chicago, close to her hometown of Gary, USA Gymnastics reported.

Durham and her husband lived in Chicago until her death.

In 2017, she was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Region 5 gymnastics, the division of USA Gymnastics that covers parts of the Midwest. She’s ineligible for the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame – it’s open only to those who’ve won a medal in the Olympics or world championships.

“As an icon and trailblazer in our sport, Dianne opened doors for generations of gymnasts who came after her, and her legacy carries on each day in gyms across the country,” USA Gymnastics CEO Li Li Leung said in a statement.

Durham loved gymnastics, even if the sport and its gatekeepers didn’t always reciprocate, and when she was on the mat, she spun through the air with the ease of a champion.