Glaciers that still exist on the surface of Mars are helping to tell the story of its past.

The red planet experienced between six and 20 separate ice ages during the past 300 to 800 million years, a new analysis of glaciers on Mars has revealed.

During the last ice age on Earth 20,000 years ago, our planet was covered in glaciers. Those glaciers then retreated to the poles. These masses of ice left behind rocks as evidence, dropping them while scraping and carving paths as they moved to the poles.

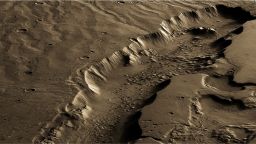

The Martian glaciers, on the other hand, never left. They have remained frozen on the planet’s surface, which has an average temperature of negative 81 degrees Fahrenheit, for more than 300 million years – they’ve just been covered in debris.

“All the rocks and sand carried on that ice have remained on the surface,” said study author Joe Levy, a planetary geologist and assistant professor of geology at Colgate University, in a statement. “It’s like putting the ice in a cooler under all those sediments.”

The study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

The glaciers on Mars have long posed a mystery to geologists who tried to determine if there was one extended Martian ice age that caused their formation or if they formed during multiple ice ages spanning millions of years.

Studying the rocks found on the surface of glaciers could answer this question. Levy determined that since the rocks erode with time, the discovery of rocks that shifted from larger to smaller in sizes downhill would suggest one ice age.

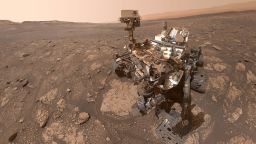

Given that it’s not yet possible to visit Mars and study its surface in person, Levy and 10 students at Colgate University in New York state used images of 45 glaciers taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The high resolution of the images allowed the researchers to count the rocks and determine their size. The magnification of the orbiter images let the team “see things the size of a dinner table” on the Martian surface, Levy said.

The researchers counted and measured 60,000 rocks altogether. Artificial intelligence would have cut down on some of the work, which took two summers to complete, but AI can’t tell rocks apart from the glacier surface.

“We did a kind of virtual field work, walking up and down these glaciers and mapping the boulders,” Levy said.

Rather than a steady arrangement of rocks differing in size, the researchers observed an unexpected randomness.

“In fact, the boulders were telling us a different story,” Levy said. “It wasn’t their size that mattered; it was how they were grouped or clustered.”

The rocks were actually traveling inside the glaciers, rather than on the outside of them, so the rocks didn’t erode.

But they were visible in rings of debris on the surface of the glaciers. These rings help to mark distinct flows of ice that formed during different ice ages.

Ice ages are caused when the tilt of a planet’s axis shifts, known as obliquity, so these distinct ice ages formed separately to reflect times when Mars essentially wobbled on its axis.

This sheds some light on the Martian climate and how it has changed.

“There are really good models for Mars’ orbital parameters for the last 20 million years,” Levy said. “After that the models tend to get chaotic.”

The team’s findings have suggested that Mars experienced multiple ice ages.

“This paper is the first geological evidence of what Martian orbit and obliquity might have been doing for hundreds of millions of years,” Levy said. “These glaciers are little time capsules, capturing snapshots of what was blowing around in the Martian atmosphere. Now we know that we have access to hundreds of millions of years of Martian history without having to drill down deep through the crust – we can just take a hike along the surface.”

The content of these glaciers could include evidence of life that may have once existed on Mars.

“If there are any biomarkers blowing around, those are going to be trapped in the ice too,” Levy said.

The discovery of the rock bands inside the glaciers is also useful information for astronauts who may one day land on Mars and drill into the glaciers to use its water ice.

The researchers will continue mapping glaciers on Mars in the hopes of learning more about the planet’s past and if life ever existed in its history.

“There’s a lot of work to be done figuring out the details of Martian climate history, including when and where it was warm enough and wet enough for there to be brines and liquid water,” Levy said.