Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced Monday that all the officers involved in a botched Chicago police raid last year have been “taken off the street” and placed on desk duty while the city’s Civilian Office of Police Accountability investigates.

Lightfoot’s move comes a day after the top attorney in the city’s law department, Mark Flessner, announced his resignation as fallout continued over the incident and questions are raised surrounding the mayor’s handling of it. Lightfoot acknowledged learning of the incident last November.

Flessner’s office, lawyers for the city who report to Lightfoot, asked a federal judge to stop CNN affiliate WBBM from airing footage of the raid and later sought sanctions against Anjanette Young and her attorney before backtracking on Friday and withdrawing the request.

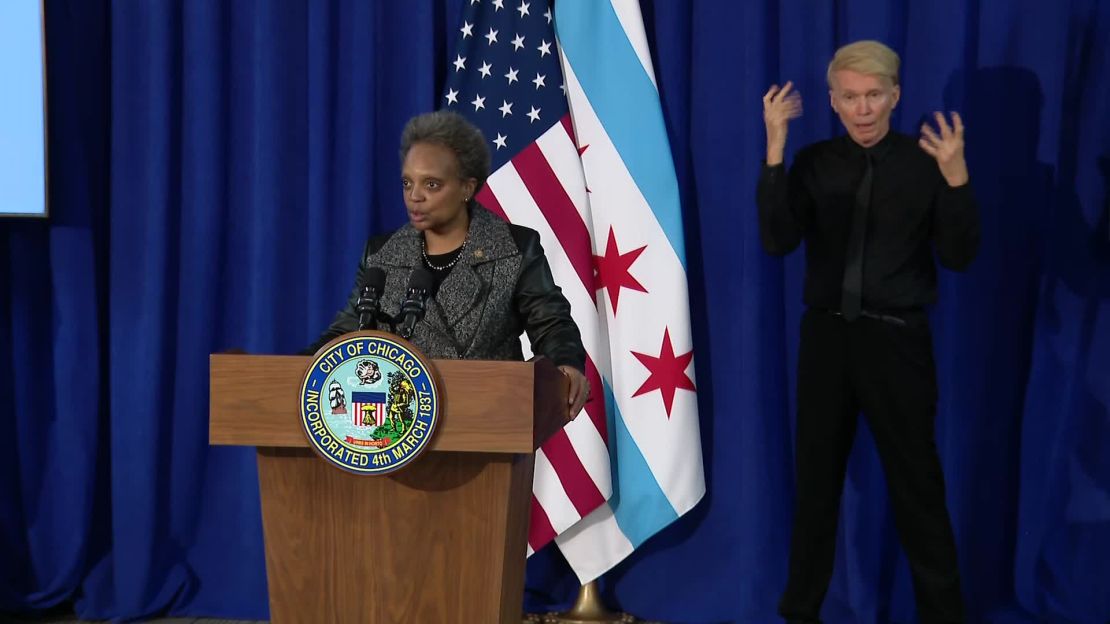

“I sought and received his resignation yesterday,” Lightfoot said in a news conference. “I firmly believe that justice delayed is justice denied. And frankly there is no excuse that this matter has languished for a year without any significant movement on the part of COPA (the civilian oversight board).”

Meanwhile, the social worker whose home was raided on the basis of bad information – and who was found naked and distraught after officers battered her front door open – is suing the Chicago Police Department for blocking the release of body camera footage.

Also, Chicago aldermen have scheduled a hearing on the case for Tuesday but said they won’t consider any legislation or take a vote. The subject-matter-only meeting of the Human Relations and Public Safety committees will give aldermen a high-profile setting to unload on police officials about the handling of the raid of Young’s home and the department’s search warrant policies.

Sunday’s resignation and other changes announced last week come as mayors and government leaders elsewhere have moved to reform police departments this year after the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black citizens.

Anjanette Young, whose home was raided in February 2019, is asking the city to release videos she requested last year. She also wants a judge to sanction the city for denying her records request in the first place.

“This mayor does not appear to have done anything on transparency, just a continuation of what Rahm (Emanuel) did and (Mayor Richard M.) Daley did before them,” said Matt Topic, the attorney representing Young. “They just refuse to follow what the law says, they’re not at a point of following the law.”

The Chicago Police Department has a history of denying open records requests, though the mayor’s office is typically involved in decisions about controversial videos. The city’s most recent mayor came under fire for blocking the release of videos showing a Chicago police officer killing Laquan McDonald as he walked away from police in 2014.

Lightfoot oversaw two police oversight agencies before running for office as a reformer and being hailed as one after her election.

On the basis of releasing videos alone, the lawsuit might already be outdated. Lightfoot released the videos Thursday but they’re tagged with an internal reference number leading back to WBBM’s records request.

“An effort to keep records about their own mistake and callous humiliation of Ms. Young from the public, (the Chicago Police Department) denied Ms. Young’s (records) request relying on legal positions that have been repeatedly rejected in prior lawsuits, and later attempted, unsuccessfully, to obtain a prior-restraint injunction against the news media to prohibit publication,” Young’s lawsuit states.

Young, who had a civil rights lawsuit pending against the city at the time of her request last year, sought all the body-camera footage from the raid. The city opened an oversight investigation after her records request, then cited that ongoing investigation as a reason for denying her records request.

Behind the raid

The raid happened in February 2019 before Lightfoot was elected. The raid was approved by a lawyer from the office of Cook County State’s Attorney Office Kim Foxx and by a Cook County judge, based on sworn testimony of an informant brought to them by Chicago police officers.

Police broke open Young’s door expecting to find a felon armed with a handgun. Instead, they found only Young, a nurse just home from work who was naked and appeared distraught as officers swarmed into her home.

One officer handcuffed and covered her, though her front was still exposed, and another brought her a blanket within about a minute. She was covered or partially covered for 12 minutes until an officer brought her to the bathroom to get dressed.

A spokesperson for the Chicago Police Department declined to answer questions about the informant or what was done to corroborate the information. A search warrant, made public in Young’s civil rights lawsuit, noted the informant pointed out the door of Young’s home and swore they’d seen the target of the warrant with a handgun and ammunition inside the apartment within the last 48 hours.

In public remarks, the mayor, the police superintendent, the state’s attorney have not stated whether anyone involved in obtaining the warrant or serving it broke any rules or laws.

Young sued the city in summer 2019, alleging her civil rights were violated. After Young’s records request was denied last November, Lightfoot’s administration asked a judge to dismiss Young’s lawsuit against the city.

The city argued the raid was lawful, even though no felon or weapon was found, because a Cook County judge and a Cook County assistant state’s attorney found probable cause to authorize the search. Before the judge ruled on the city’s request to dismiss the case, Young’s lawyer asked for the body camera footage.

The judge ordered the city to turn over body camera videos but also ordered the videos and other records provided be kept confidential. Young’s lawyer then asked the judge to dismiss her federal lawsuit, and the judge did.

If the judge had dismissed the suit at the city’s request, it would have been more difficult for Young to pursue a civil rights complaint against the city. Because the judge dismissed it at Young’s request, her attorney is free to again pursue the matter in federal court.

Almost nine months after the case was dismissed, and without Young’s attorney refiling the case in federal court or seeking other damages in state court, WBBM informed Lightfoot’s administration that it was planning to air footage of the raid. That’s when city attorneys sought to bar WBBM from airing the footage and also accused Young’s attorney of violating the judicial confidentiality order after Young’s lawsuit was dismissed.

Lightfoot apologized for her city attorneys trying to restraining WBBM and reversed position on the sanctions against Young’s attorney after an outraged city alderman called a special City Council meeting.

A federal judge has scheduled a hearing in the matter for Tuesday. Young’s lawyer has since retained an attorney of his own.