When they brought him his passport, Jeff Harper thought he was getting out.

He stared at the document, its navy cover embossed with the United States seal, as it gradually dawned on him that the Chinese police officer, in his broken English, was describing something quite different.

“He said something about a residential surveillance house,” Harper said. “I had no idea what that was.”

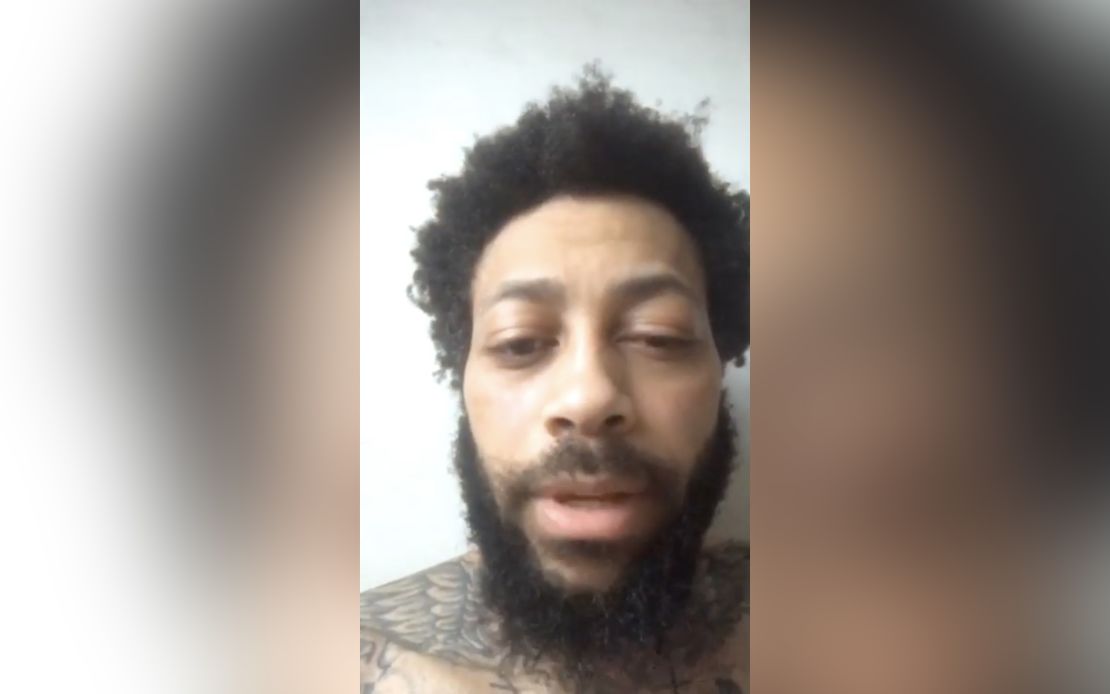

It was early January 2020. Harper, a 6-foot, 8-inch (203 centimeter) professional basketball player, had arrived in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, hoping to land a new contract after playing in Norway, Japan and a host of other countries.

Harper had been in China for less than a week when everything went wrong. Walking back from a comedy show with a friend in the early hours of January 7, he said he saw a violent altercation between a man and a partially clad woman on the street and ran over to help.

According to Harper, he pushed the man out of the way, causing him to fall to the ground. The man then left the scene, Harper said. He and his friend checked that the woman was OK, were told she was, and Harper returned to his hotel.

Hours later, police turned up at his door. In the intervening hours, the man he’d shoved had turned up in hospital, they said, and was now in a coma.

Harper texted his girlfriend back home in Boise, Idaho: “I’m in some trouble.”

Victoria Villareal said that when she finally got Harper on the phone, “the first thing I asked was, ‘Were you trying to help somebody?’”

She spoke to Harper in the police station, as the cops decided whether to charge him and before they confiscated his phone and passport. It would be two weeks before Harper saw that document again, in the hands of the officer he thought was coming to release him.

But the man Harper says he pushed had not woken up from his coma, and soon after Harper was moved to “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL), a system by which people can be detained in China for up to six months without charge. There, he was informed that the man had died. The exact circumstances of the man’s injury and death remain unclear, police did not respond to a request for further information.

A police document seen by CNN, dated January 20, said Harper was being investigated for causing serious injury by negligence. Harper did not dispute that he had pushed the man but said he did not appear to be seriously injured when he left the scene of the original incident.

As it was sinking in for Harper that he was not going home to Boise anytime soon, Villareal was frantically researching lawyers in Shenzhen, contacting US diplomats, and emailing and calling anyone she knew who might have some experience with China.

This brought her in touch with Peter Humphrey, a one-time journalist turned corporate investigator, who had an intimate knowledge of the Chinese legal system. In 2013, it had been Humphrey who was sitting in a Chinese cell waiting to find out what would become of him, the start of almost two years in various forms of detention, for a crime he says he didn’t commit.

Since his release and return to the United Kingdom, Humphrey has transformed himself into an antagonist of those he blames for putting him behind bars, and an unpaid adviser and lobbyist for those still there. Despite ongoing health problems, which Humphrey said had been exacerbated by his time in prison, this has become something of a mission for the 64-year-old, a second act he never expected.

“I understand these things, I’ve lived through it, that’s why I open my heart and calendar to a number of people in this situation,” Humphrey said. His advice spans the gamut from dealing with the often arbitrary and confusing Chinese legal system, to what families can expect from their countries’ diplomats, as well as how to support loved ones on the inside from thousands of kilometers away.

For Villareal, Humphrey’s experience and advice was invaluable: “If I hadn’t got a hold of Peter, it would have been a whole lot tougher, Jeff might not be here right now,” she said.

The investigator

Originally from the United Kingdom, Humphrey first went to China as a 23-year-old postgraduate student.

It was 1979, and Humphrey joined a two-year exchange program at the Beijing Language Institute, later taking up what he called “the rather privileged position of ‘foreign expert’.”

Outside his teaching responsibilities, this gave him the ability to travel around the country, at a time when China was still relatively closed off and internal travel among foreign nationals heavily restricted. “I had much more access than most journalists or diplomats,” Humphrey said.

He had an interest in journalism and started freelancing for a number of publications under a pseudonym, as well as briefly joining the founding staff of the China Daily, a state-run English language newspaper, in 1981.

Humphrey found working at a government propaganda organ claustrophobic, however, and soon moved to Hong Kong, then still a British colony. He spent a year at the South China Morning Post newspaper, before moving to London to join the Reuters newswire, which, after a decade or so in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, sent him back to Hong Kong in 1995 to cover the city’s impending handover to China.

“After the handover I decided I wanted a change of career and professional occupation,” Humphrey said. He began consulting, using his journalistic skills to investigate companies and deals, focusing on due diligence and corporate malfeasance.

In 2003, Humphrey co-founded ChinaWhys with his wife Yu Yingzeng, a longtime financial fraud investigator. The pair soon started working for the various multinationals that had rushed into China after Beijing joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

One of those companies was GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceutical giant. According to court documents in a case Humphrey and Yu later brought against GSK, ChinaWhys was hired in April 2013 to investigate allegations that the company was involved in a bribery scheme which involved paying doctors off in China who would in turn prescribe the company’s medications.

GSK bosses called it a “smear campaign” being waged against them by an aggrieved former employee in the China office. According to the court documents, Humphrey and Yu were told the former employee had sent allegations of bribery and other misdeeds at GSK to Chinese regulators, as well as allegedly circulating a secretly recorded sex tape of GSK China boss Mark Reilly to other company executives.

Within a year however, GSK would end up convicted of offering bribes to boost its business and forced to pay a fine of nearly $500 million to Chinese regulators in late 2014. GSK apologized, admitting that its China operation had broken the law as well as company rules. Former China head Mark Reilly was deported after being given a suspended prison sentence of three years, state news agency Xinhua reported. CNN has been unable to reach him for comment.

By this time, the Chinese authorities had also turned their attention on Humphrey and Yu, who they accused of obtaining private information by “illegal means.”

The couple were arrested in July 2013, and spent over a year in pretrial detention in a Shanghai jail. They were eventually convicted the following August. Humphrey was sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison, while his wife received a two-year sentence.

Humphrey described the prison system in China as “inhumane and too harsh,” with “all these cases based on extracted confessions and sentencing which is completely reckless.” Experts estimate that around 99% of criminal prosecutions in China end in a guilty verdict, meaning there is little defendants can do but try and make their time in prison as bearable as possible and look for ways to get out early, either through international lobbying or on health grounds.

The rulings hinged in large part on involuntary confessions by both Yu and Humphrey, broadcast during prime time on state television, which the couple says they were forced into “under conditions tantamount to torture.”

China has previously denied using torture to force confessions. Commenting on Humphrey’s case earlier this year, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said it had been handled in “accordance with law.”

Stuck in Shenzhen

On January 20, 2020, Jeff Harper was moved from police detention to a nondescript apartment building elsewhere in Shenzhen.

There, he said he spent the next six months in almost complete isolation, without reading materials and with only sporadic communication with the outside world.

For months, Harper said he was largely unaware of the coronavirus pandemic as it first hit China, only that health concerns meant consular officials could no longer visit him in person. He also didn’t know about Kobe Bryant’s death (though some of his relatives urged Villareal to tell him) or the Black Lives Matter protests then sweeping the US.

“I used to cry because I couldn’t talk to (Victoria),” he said. “No one spoke any English, I tried to use the translator (app) they gave me, it was a piece of crap.”

He feared the police were trying to make him go crazy but didn’t know what they wanted from him. He didn’t know if they were trying to prompt a confession, due to the language barrier.

Back home in Boise, Villareal was trying desperately to hold it together herself, as she continued to search for anyone who could lobby on his behalf.

“I couldn’t talk to (Jeff) and see what was going on, I didn’t know what was going on,” she said. “Talking to Peter was great because I didn’t cry a whole lot in the beginning, until he asked, ‘How are you?’ Peter knew what it was like to be on the other side of this, because his son went through that.”

Humphrey helped explain the Chinese legal system and make sense of some of what Villareal was hearing from Harper’s lawyers. He also connected her with John Kamm, founder of the Dui hua Foundation, which lobbies on behalf of detainees in China.

“John had all the information, he was able to help me be at ease,” Villareal said. “He kept saying this was such a weak case against (Harper).”

Both men were confused about the authorities’ apparent reluctance to charge Harper, telling Villareal that they’d never seen a situation like this before – not something that necessarily brought her much comfort.

“From what I could see, this was all very peculiar, the circumstances of his detention were so weird,” Humphrey said. “I was even concerned at one point that this might actually be a kidnap and extortion situation dressed up as an arrest.”

Villareal and Harper’s lawyers had the documents showing the case was official, however, though they could not understand why the authorities were dragging their feet on bringing a prosecution. Police and prosecutors in Shenzhen did not respond to CNN’s request for comment on Harper’s case.

The prisoner

Before his trial, Humphrey also spent months in the Shanghai Detention Center – a more formal system than RSDL – before he was transferred in mid-2014 to Qingpu Prison, on the outskirts of the city.

There, he was held in a special cell block for foreign prisoners. The conditions were miserable, with 12 men to a room, sleeping on hard, metal bunks and thin mattresses, he said.

Food was limited and what they did get was barely nutritious, and Humphrey worried constantly about his health. He had been diagnosed with suspected prostate cancer before his arrest, but he said prison officials dismissed his pleas for a follow up examination or treatment unless he signed a confession, which he refused.

Partly to pass the time, Humphrey began interviewing other foreign prisoners, learning about their stories.

“During those two years, I met very few (prisoners) who really deserved the sentences they were serving,” he said, adding that some of the men he knew were in for crimes of the type “I could have potentially been investigating … when I was on the outside.”

While Humphrey was broadly aware of criticisms of China’s legal system and prison conditions before he was subject to them himself, he said that as an investigator, “I would sometimes share my client’s sentiment that we wanted a bit of blood, send these guys to jail.”

“Those two years completely changed my mind,” he said. “Prison life was very harsh. If you want someone to rehabilitate, you have to at least allow them dignity. They took that dignity away. I came away from it feeling tremendous empathy for most of the prisoners I met.”

In an account of his time in Qingpu, written after his release, Humphrey said he and other foreign inmates spent much of their time on “manufacturing jobs,” primarily making “packaging parts” for foreign brands.

“Prisoners from Chinese cell blocks (also) worked in our factory making textiles and components,” Humphrey wrote. “They marched there like soldiers before our breakfast and returned late in the evening.”

In April 2015, after 21 months of lobbying by Humphrey and British consular officials about his health, prison authorities agreed to send Humphrey for an MRI at a local hospital. This confirmed his original doctor’s suspicions: he had a tumor in his prostate.

Prison officials started discussing a potential reduction in Humphrey and Yu’s sentences, should they admit guilt and express remorse. Eventually, after the pair signed what Humphrey described as a “highly qualified” statement, in which they did not explicitly admit any of the crimes they were accused of, the couple was released.

In the UK, Humphrey immediately began radiation and hormone treatment for cancer, which had by then reached an advanced stage in his prostate. He said doctors told him that if it had been treated two years earlier, this might have been avoided.

Humphrey also began seeking justice.

“While we were trying to fix my health, we started an investigation into ourselves and our case,” he said. “There was nothing we could do while we were locked up, we couldn’t even have legal documents in the cell, we didn’t know what was in the media.”

Just as if they were investigating any normal case of corporate malfeasance, they began writing a report about their mistreatment and injustice in Shanghai, the GSK connection and the company’s alleged links with corrupt officials, and submitted it to the Beijing government.

They also sued GSK in the US. According to their initial case filed against the company, Humphrey and Yu claim they were hired as consultants based on “false statements” to them by GSK to do work that eventually led to their “conviction and imprisonment in China, and the destruction of their business.”

While an attempt to sue GSK in federal court was dismissed by a judge on procedural grounds, the couple also sued GSK in state court in Philadelphia, where its US headquarters is located. That litigation is ongoing, with a court late last year rebuffing GSK’s attempts to force it into arbitration, a process that would have taken place in China.

Asked for a comment on the litigation and allegations made by Humphrey and Yu, GSK would only say that its position is that the case “belongs in arbitration” in China where the couple’s work took place and that the company believes it will prevail in this argument at the Superior Court of Pennsylvania.

John Zach, who represents Yu and Humphrey, said that GSK “has made repeated efforts to delay this matter and prevent Peter and Ying from having their day in court,” and was trying to move the case to China, where the pair “cannot safely travel and where this matter cannot be fairly tried.”

Humphrey also looked into other ways of striking back. Chinese state broadcaster CCTV had aired Humphrey’s forced confession, in which, dressed in a prison issue uniform and looking semi-conscious, he “apologized to the Chinese government.” (Humphrey maintains this apology and apparent confession was under duress.)

In the UK, CCTV and its English-language arm CGTN are licensed by Ofcom, the national television regulator, which in July ruled on a case brought by Humphrey and others that the Chinese broadcaster was in “serious” breach of its obligations by airing the confession, in which “material facts were presented, disregarded or omitted in a way that was unfair to Mr Humphrey.”

“There were a number of battles we selected to fight, in one of them we scored a victory, others are still ongoing,” Humphrey said.

Benedict Rogers, a human rights activist based in the UK with a focus on China, said Humphrey’s public stance against CCTV and other testimony was important in pressing the British government to take a harder line towards Beijing.

“Having someone who had done business in China and ended up in that situation was very powerful and compelling because it wasn’t just a human rights story,” Rogers said of a hearing on China that he organized for the ruling Conservative Party. “He can’t be dismissed by people who might not have an interest in meeting human rights activists. I think his voice both in advocacy and in support for other families in similar situations is crucial, really.”

Responding to Ofcom’s ruling against CGTN earlier this year, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian described it as a “wrong decision.”

“As for the case of Peter Humphrey, I want to reiterate that China is a country ruled by law. The Chinese judicial organs handle cases in accordance with law and in this process protect the legitimate rights of foreigners in China,” Zhao added.

The advisor

While he was seeking redress, and fighting the cancer that threatened to kill him, Humphrey also remained in touch with some of the men he had met in prison.

“I began to write to one or two of the prisoners under an alias,” he said. “All the letters going to the prisons are looked at, but I managed to communicate with a few, and did what I could to help them.”

He sent reading material to his former cellmates and interviewees and got in touch with some of their families around the world.

“I developed contact with a few families of prisoners outside to try and brief them properly and mentor them on how they could potentially lobby for their family member’s relief,” he said. “This grew into me taking an interest in new cases.”

One of these involved Kai Li, an American man, born in Shanghai, who moved to the US and became a US citizen. He has been detained in China since 2016, and is now being held in the same Shanghai prison where Humphrey suffered.

Li was convicted of espionage in 2018, in a case his family maintains was trumped up and politically motivated. After CNN reported on his story earlier this year, Humphrey got in touch with Li’s son, Harrison.

“One of the things I’ve done is give him a better understanding of what his dad has been going through in there, and ways he can try to prop up his dad’s morale,” Humphrey said, such as sending books and other reading materials, and offering encouragement during tightly monitored phone calls from the prison.

While Harrison Li has been an active and effective campaigner on his father’s behalf, even temporarily relocating to Washington to lobby lawmakers, he said it was useful to speak to someone with knowledge of all aspects of his father’s case, from Chinese legal issues to the delicate balance of getting publicity for it.

“He was particularly helpful on reaching out to the media and things like that,” Li said. (“I mentored him on how to manage people like you,” Humphrey told CNN.)

Humphrey has given similar advice to other families, as well as explaining how diplomats and consular officials are often unable – or even unwilling – to get too involved in their cases.

“A lot of victims’ families don’t realize that basically consular officials are not working for them, they’re working for their own government,” Humphrey said. “They’ve got protocols and practices in place that limit what they can do.”

He added that many countries regard China’s legal system as they do any other, and so are wary of intervening in many cases, something Humphrey said was “complete idiocy, because you’re not dealing with a country under the rule of law.”

There’s a model for Humphrey’s transformation – from somewhat skeptical believer in the Chinese system, to victim of it, to an opponent – said Peter Dahlin, co-founder of Safeguard Defenders, an NGO that works to support human rights activists in China.

“It all starts with a personal experience. Someone has a family member detained or their land taken, and they start fighting back, and that doesn’t work, so they take on the issue at large rather than just their personal situation, as a way to seek justice for others as well as seeking justice for yourself,” he said. “This is literally 99% of activists I’ve met in more than 10 years of working on China. It’s very rare to see this with a foreigner, but that’s what happened with Humphrey after his time in prison.”

Dahlin was himself detained in China in 2016 and forced to make a confession on state TV, and has worked with Humphrey to lobby against the practice and hold CGTN to account.

“Most of the victims (of forced confession) are Chinese of course, and foreigners are still a rarity,” Dahlin said. “But these cases can be very handy to use in campaigning in certain countries.”

A rare victory

As Harper’s detention dragged on, month after month, his treatment began to improve, and he was permitted to call Villareal more often.

“The deadline was supposed to be up in October,” Villareal said. “I knew we were going to get a decision, either a charge or they let him go home.”

In the early hours of August 20, Villareal, now operating largely on China time, received a text message from Harper’s lawyer, saying they were going to visit him.

“She said there was news, and they’d call me after they got over there,” Villareal said. “I’m sitting here panicking. The last time they had a meeting like this was when the man (Harper pushed) had passed away.”

She started inundating Harper’s phone with text messages, asking: “WHAT IS HAPPENING?”

Finally, Harper video-called her. She could see his lawyers standing with them, and then noticed something weird about the background: he wasn’t in the detention room.

“Where are you? What’s happening?” Villareal said.

“I’m not in there, I’m out,” he responded. She could hear the lawyers laughing in the background. “I’m out.”

Hours earlier, a prosecutor had come to see him and handed Harper a document. He listened impassively as it was translated for him.

“I heard ‘you’re innocent,’ but I couldn’t believe it because of what had happened last time,” he said.

Villareal emailed Humphrey the document, an official decision by the prosecutor not to pursue the case, as well as a notice informing Harper that “we decide to lift your residential surveillance at a designated location order, in accordance with article 79 of the Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China.”

“I’ve never seen one of these documents in my life,” Humphrey said. “No indictment, no charge, passport returned, free to go.”

But while Villareal was ready to celebrate, Humphrey noticed a “sting in the tail.” A copy of the document seen by CNN said that if the victim – in this case, the dead man’s family – “disagrees with this decision,” they could appeal “within seven days … and request public prosecution, or can skip appeal and directly file a private prosecution.”

Humphrey warned Villareal the ordeal wasn’t quite over. And nor could Harper head immediately for the airport: he had to get an exit visa, his own tourist permit having long expired.

That was initially supposed to take three days, but it was delayed, and then delayed again. After 10 days of sitting in a hotel room expecting the worst, Harper got the requisite stamp and headed to Guangzhou to fly home to the US.

Humphrey told Villareal to stay in touch with Harper the whole time he was traveling. “I said he’s not free while the plane is on the ground, and make sure you tell me when it’s airborne,” Humphrey said.

Harper said Villareal had been “very strict with me, telling me not to speak to anybody.” He walked through the airport with his head down, avoiding eye contact, something that was made easier by the place being almost completely empty, due to the coronavirus.

Even when the plane took off, as Villareal and Humphrey were celebrating, Harper couldn’t shake the fear that there might be an emergency landing, or that the flight would turn back.

“I sat in the same seat and didn’t move for 13-and-half hours,” he said. “It wasn’t until I got through customs that I felt I was home free.”

Finally, after another connecting flight, he was reunited with Villareal. The pair are now trying to get their life back on track in Boise, their savings drained by over six months of legal fees and lost earnings, facing the threat of a civil lawsuit in China from the family of the man Harper pushed.

“We’re definitely still not used to it,” Villareal said. “He’s different, I think I’m a different person.”

But they’re still in love, and plan to get married when the pandemic ends. Harper is done playing basketball overseas, instead he’s focusing on teaching children everything he knows about the sport, and he plans to give inspirational lectures based on his ordeal.

“He’s been to 13 countries now, so I think we’re good,” Villareal said of her fiancé’s former lifestyle. “I think we’ll try to travel within the 50 states in future.”

For Humphrey, Harper’s case is a rare victory in a career he never intended to have, one that often involves commiserating with and supporting people whose loved ones will be locked up for years to come.

The day before he spoke to CNN, from his home in Surrey, Humphrey had his first video call with Harper, a man he had never met but had spent many weeks trying to get out of prison.

“We had our first video call, the three of us,” Humphrey said. “Personally, you know, this case is antithetical for me, because most of the time I’m telling bad stories. But here’s a story that has a happy ending.”

Main illustration by Max Pepper.