A young woman sits by a hospital bed as she gently strokes the hair of a withered figure. At first glimpse, it looks like it could be a child, but the grey hair finally gives a man away.

Lying, face down, is her 69-year-old father. His thin, frail, shivering body is nearly disappearing beneath a thick set of blankets. “He’s very cold,” she says, without stopping stroking his hair, barely turning to face us. “They gave a treatment and he said it was very cold,” she added, referencing the IV drip he had just been given.

Her father suffers from malnourishment, a plight that has become common among Venezuelans. He needs iron supplements, but Vargas Hospital in Caracas, where he is being treated, simply doesn’t have any. His daughter will have to get hold of the medicine herself or doctors say his hemoglobulin levels will remain low.

His immune system is compromised, yet medical staff tell us he shares this ward with patients with diseases so contagious that, in most countries, they would be isolated from the rest. Among them, medical staff tell us, is a patient with Covid-19.

It’s the dangerous overlap of the malady the impoverished Venezuelan state has imposed on its citizens, with a global health emergency that has largely ground the world to a halt.

Years of government mismanagement have left Venezuelan healthcare grossly unprepared and under-resourced to handle the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the past decade the country has squandered most of its oil wealth, plunging into a deep economic crisis and humanitarian crisis. Venezuela boasts the largest proven crude oil reserves on the planet, but a sharp drop in oil prices in 2016, sparked an economic implosion, leading to hyperinflation as well as shortages of basic goods, such as food and medicine.

Most hospitals and clinics in the country have seen government funding steeply cut and are on the brink of collapse, surviving by the sheer will of the healthcare workers that continue to show up. “There’s nothing in this hospital, not even scrubs,” a senior medical worker who, like many others in this story, spoke to us under the condition that she remain anonymous for fear of government reprisal, tells us. “It’s our calling and we want to do a good job, but with the low salaries that we have … we have to claw our way through.”

Nurses like her usually earn around $3 dollars per month in Venezuela, unions have told us. Support staff and doctors here make about $1 and $5, respectively, they also told us.

The smell of disinfectant is notably absent here – there isn’t any left – and at the end of the ward, in a unit seemingly no longer in use, two dead rats lie on the floor. They’ve been there for days, she says. The derelict state of Venezuela’s once renowned hospitals is no secret, and as the coronavirus sweeps through the country many patients are choosing to face the pandemic at home, fearing their chances of surviving the virus are far worse inside the facilities, healthcare workers tell us.

The government strategy

According to official government accounts, Venezuela seems to have been spared the ravaging impact that the virus has had in other countries across the region. With 104,442 confirmed cases and 919 deaths from Covid-19, according to the government’s official tally, Venezuela appears to be one of the least affected countries in all of Latin America, a fraction of its neighbours Brazil, Colombia and Perú.

Embattled President Nicolas Maduro has largely declared victory against the virus, saying doctors, nurses and other staff were able to respond to Covid-19 “under the unified institutions of the State,” in a speech on Thursday.

The authoritarian regime has responded to the virus with force, issuing strict precautionary measures and commandeering hotels and motels to quarantine suspected Covid-19 patients for weeks on end.

Suspected patients can be held under this state-managed quarantine for up to 21 days, officials say. Some patients, however, have told CNN that it can be longer, sharing harrowing stories of the abandonment and isolation they experienced inside.

Dr. Richard Rodriguez, who works at one of these government-run facilities, tells CNN, “We know that maybe (motels) are not the best conditions, these are not five-star hotels, but at least they have a doctor, a nurse, emergency personnel that are available to attend to them when necessary.”

Under the watchful eye of a government minder, Rodriguez adds that “Venezuelans have a strong immunity against the virus.” He swears he’s never saw any shortages in medical supplies or protective equipment. “We had all the supplies, and the equipment we needed,” he concludes.

But that’s a far cry from what many health workers at Vargas and other hospitals tell CNN. Most medical personnel we spoke with disagree with government reassurances about their healthcare system’s ability to handle the pandemic — and are raising doubt about official statistics on the pandemic’s toll on Venezuela.

Experts say the number of deaths and cases may be severely underreported due to insufficient testing, and overreliance on rapid antibody testing, which is considered less reliable than the WHO-recommended PCR tests.

CNN reached out to the Venezuelan government for comment on the conditions seen in these hospitals in Caracas and also on criticisms by healthcare professionals, but did not receive a response.

Fearless physicians

Venezuelan doctors, academics and journalists have been targeted for criticizing the government for its response to the pandemic, many facing criminal charges for allegedly disseminating false information

One Caracas doctor, Dr. Gustavo Villasmil, tells CNN that he has felt pressured to stop talking about the government’s pandemic response – but that it won’t keep him from speaking out. We met him at the Caracas University Hospital, just outside his office, near the parking lot, where he quickly directed us towards another area, across the street, away from the facility and closer to the university campus.

“I was warned ‘colectivos’ would be circling around today,” he says, referring to the pro-government paramilitary groups that have played a growing role keeping Maduro in power.

Villasmil says dismal healthcare conditions are common across Venezuela. “Last year, no Venezuelan hospital had running water 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” he tells us, citing a survey of healthcare facilities in Venezuela. “You can deduce how a surgical area or an emergency area or an intensive care area is managed where this service is required.”

With testing limited to only three government-controlled labs, he adds that it is impossible to assess that Venezuela has dealt with the virus successfully. “With regards to Covid we don’t know where we are,” he says. “In Venezuela there are only as many recognized Covid cases as the regime has wanted.”

His views are shared by several doctors, nurses and medical staff interviewed by CNN in Caracas, including Dr. Julio Castro, an infectious diseases expert and professor at the Institute of Tropical Medicine at the Central University of Venezuela, who leads the National Assembly’s commission on the coronavirus and advises government officials.

Castro says that what is happening inside hospital wards across the country does not support the coronavirus case numbers put forward by the government. “You see the official numbers, they are going down very, very quickly,” he says, while in hospitals, doctors report seeing the exact opposite. “In the last three weeks, we have seen a rise in the numbers of the cases in the emergency room.”

Lack of testing and delayed results are complicating matters, he adds. “We have right now a patient in the ICU, that has been admitted for seven day and we didn’t have a PCR confirmation until yesterday,” Castro says. “The average (wait for PCR test results) in Caracas right now is close to a week or 10 days.”

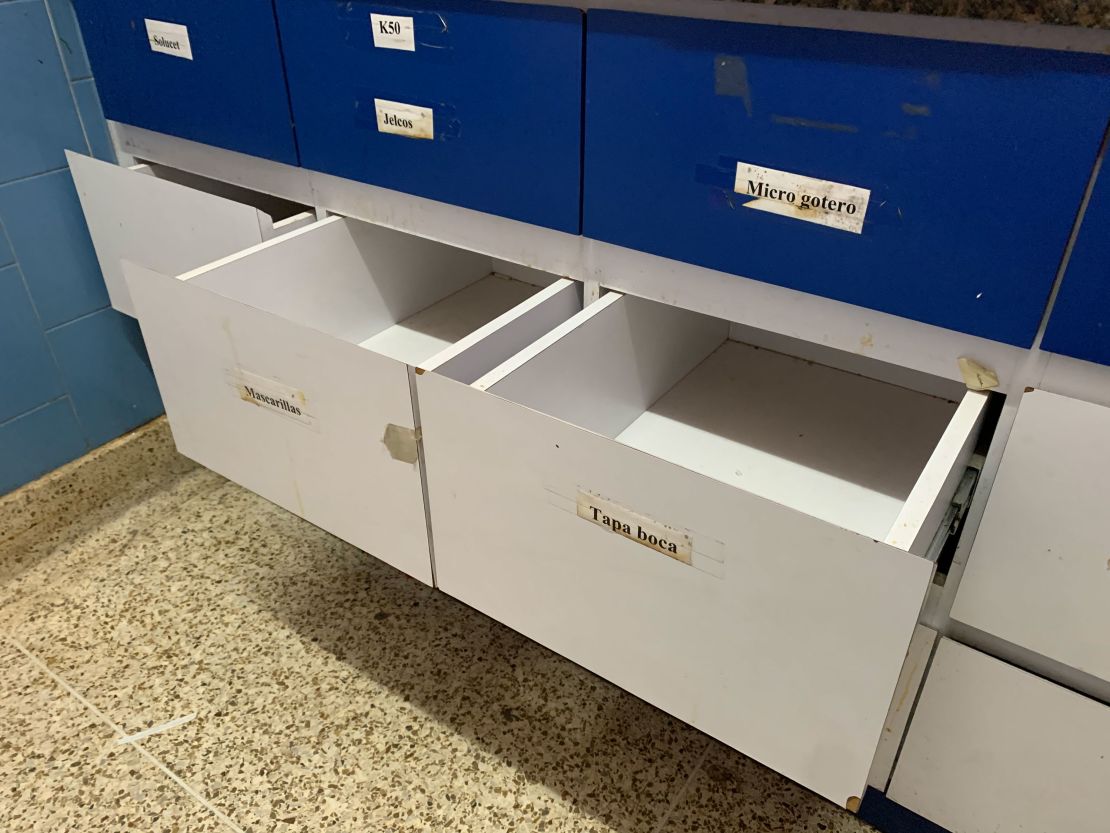

Staffers at Vargas hospital told CNN they had to fight tooth and nail for every piece of equipment, most of which they end up having to buy themselves. “I’ve had this mask for roughly five days,” one nurse told us, as she adjusted the elastic on one side. “They don’t give us means to keep ourselves safe, they don’t give us gloves, they don’t give us masks,” she said, showing us the hand sanitizer bottle she carries around with her and which she had to buy herself.

And they’ve have paid a heavy price. More than 270 health care workers in Venezeula have died from Covid-19, according to Medicos Unidos de Venezuela, an NGO that supports doctors and other healthcare workers, accounting for nearly a third of the fatalities reported by the Venezuelan government. The percentage is much higher than in other countries in the region and across the globe – another reason why many Venezuelans question the government tally.

At another hospital, Los Magallanes, which serves some of the poorest in the capital Caracas, even the dead are underserved. Most of the wards here are now empty, their doors chained, and electricity and water cut off. In the morgue, there’s only one loud working freezer and the electricity comes and goes. The stench is unbearable. The smell of decaying bodies pierces through our masks. Staff here tell us there’s no pathologist in the hospital, and the space appears abandoned, with dry blood stains covering the walls, and used supplies scattered across two autopsy tables.

Many of those that end up here die without ever being diagnosed.

The medical worker showing us through the desolate rooms says he’s been working here more than a decade and has never seen hospital conditions get this bad. “The constitution clearly says that the government is the guarantor of the health, of the safety, of the alimentation of all Venezuelans,” he tells us.

“They keep saying this is all well but that’s a lie.”