This week, Venezuelans are being asked to go to the polls not once but twice, in two bizarrely conflicting electoral events.

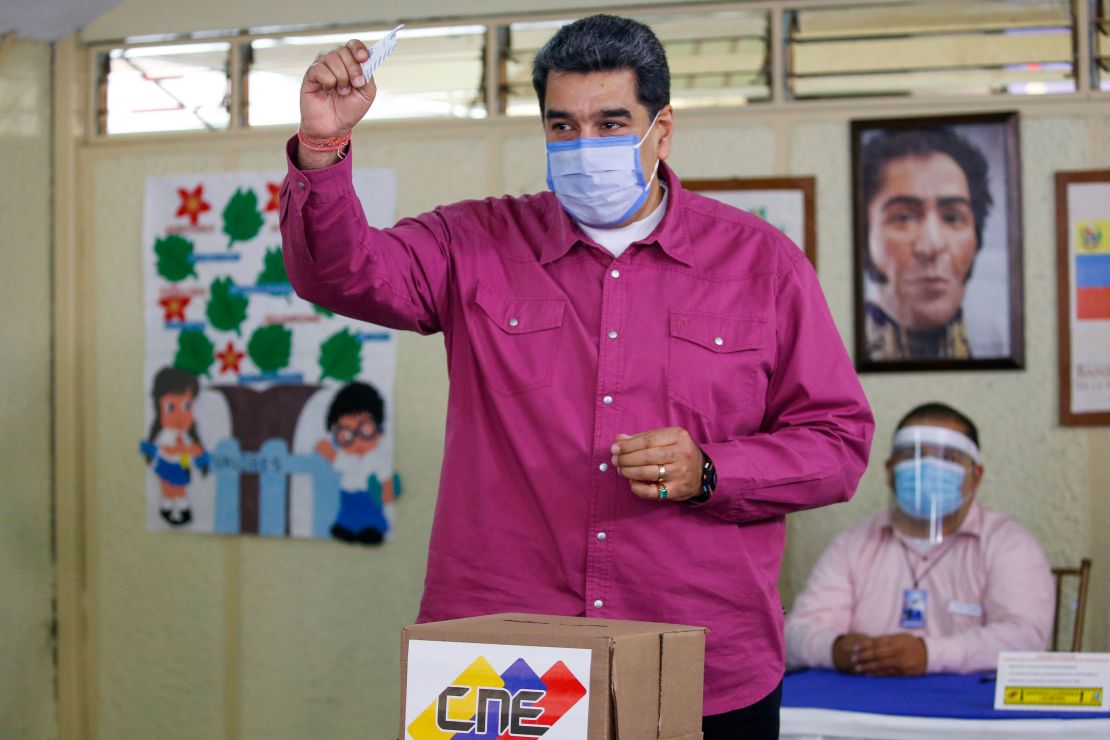

On Monday, December 7, the government of embattled president Nicolas Maduro celebrated victory in parliamentary elections, largely rejected on the international stage.

Now, the opposition is holding a competing referendum to gather support and reject the outcome of the weekend’s vote.

It’s the latest split-screen episode in a years-long saga of Venezuela’s rival presidencies – and some observers fear it may also be one of the last.

For the past two years Venezuela has effectively had two dueling presidents.

In May 2018, sitting president Maduro was proclaimed the winner of a presidential election that was seen as shaky from the start. His opponents refused to concede the result, alleging fraud.

Even Smartmatic, the electoral product company that had managed previous elections in Venezuela, said it could not guarantee the validity of election results.

But Maduro paid little notice and inaugurated his second term.

This led the opposition to rally around the president of Venezuela’s Parliament, a young lawmaker named Juan Guaidó, who – according the constitution – must rule ad interim should the presidency be vacant.

Guaidó was sworn in as interim president in January 2019. More than 60 countries have recognized his presidency, including the EU, the UK, Canada and most of Latin America.

But Maduro kept the support of China, Russia, Cuba and Iran, and control of the state apparatus, so while Guaidó’s claim is de jure, Maduro is the de facto ruler in the capital city, Caracas.

By staging competing elections, both parties are now essentially trying to build up their claims of legitimacy: Maduro by expanding control of state institutions in order to please international creditors, and the opposition by organizing their own parallel event to urge the international community not to abandon them and their supporters.

Maduro’s gamble

According to official results released early on Monday, Maduro’s party received 67% of the ballots in a vote where fewer than one in three voters bothered to turn up.

Despite the low turnout, Maduro celebrated the result, hailing Sunday’s election as “a great victory for the democracy and the constitution.”

Both the US and the EU have already announced they will not recognize Sunday’s parliamentary election, but the new parliament it creates will nevertheless work on Maduro’s behalf and further strengthen his control of the state.

According to the Venezuelan constitution, commercial treaties and oil deals must be ratified by Parliament to go into effect. Clearing out the conflict between the executive and the once-independent legislature is seen as desirable for international creditors, such as China, who continue to invest in the flagging Venezuela oil industry.

The election also erodes the legitimacy of Guaidó and the opposition movement, by removing them from control of the country’s main legislative body.

Most of the opposition had already decided not to participate in the election, calling it a fraud from the beginning.

In the last five years, Maduro’s courts have banned opposition political parties, sent lawmakers to jail despite parliamentary immunity and replaced opposition party chiefs with politicians less hostile to the government.

The EU made a last-minute attempt earlier this year to send electoral observers if the election was postponed to early 2021 because of the pandemic, but Maduro insisted the elections had to take place in December, and as a result only a few international observers invited by the government audited the vote.

On Sunday night, Guaidó highlighted the low turnout of the parliamentary election, calling it “a fraud nobody believes in.”

The opposition’s own referendum, which begins on Monday, will ask Venezuelans three questions: If they want free and fair presidential elections to remove Maduro from power; if they reject the results of Sunday’s parliamentary elections; and if they will give the current opposition leadership a mandate to “effort actions to bring back democracy, look after the humanitarian crisis and protect the people from human rights violations.”

The vote is cast online through a dedicated app or a Telegram channel, and open to both Venezuelans home and abroad, to tap into the largely anti-Maduro Venezuelan diaspora. The opposition expects between three and six million people to take part, and hopes to emphasize to both Maduro and the international community the legitimacy of Guaidó’s claim to the presidency.

What comes next

This week’s events are unlikely to change the current reality. Despite the competing claims, Maduro is already the practical leader of Venezuela, and the opposition has been reduced to its nadir over the past two years, with several top figures fleeing abroad.

“To quote Churchill, we are going through the darkest hour of our Republican history,” Humberto Prado, an opposition figure and close ally of Guaidó, told CNN.

As the coronavirus pandemic sweeps the globe, Venezuela is hardly among the top priorities for other nations. Though US President-elect Joe Biden has labeled Maduro “a dictator, plain and simple,” he has already ruled out imposing a change of regime by force.

Europe is yet to find a unified position on Venezuela: while some countries like Germany or France have openly supported the opposition, other members of the 27 have been more cautious.

And Spain, arguably the EU country most involved in Venezuela, recently changed its ambassador to Venezuela, replacing a diplomatic veteran close to the opposition with a former ambassador to Cuba – a sign perhaps that they don’t see Maduro packing his bags anytime soon.

This doesn’t mean that things aren’t changing.

Life in Venezuela is measurably worsening: the IMF predicts the Venezuelan GDP to fall a further 25% this year, inflation is 6,500% on the previous year and 94% of the population live below the poverty line, according to three independent universities in Caracas.

But that may not be as politically significant as strategists abroad once hoped.

“The idea that all of this is unbearable and will have to crack is nonsense. Look at Cuba, North Korea, Zimbabwe. This can go on for long, and those who are having a harder time can leave and this benefits the government once again,” Luis Vicente León, a pollster and political analyst in Caracas, told CNN.