Covid-19 is spreading faster than ever before in the United States, with hospitals in some states running at capacity. The country is now in the same situation that France, Belgium and the Czech Republic were last month, when rapidly rising infections put their health care systems within weeks of failure.

But these countries have managed to avert, for now, the worst-case scenario, in which people die because hospitals are full and they can’t access the care they need to survive. They slowed down the epidemics by imposing lockdowns and strict mask mandates.

Despite the clear evidence from Europe, the White House is still opposing new restrictions. “President Trump wanted me to make it clear that our task force, this administration and our President, does not support another national lockdown. And we do not support closing schools,” Vice President Mike Pence said Thursday, at the first White House coronavirus task force briefing since July.

“It’s evident that in the US, cases are still rising, or at least they’re not going down,” said Mike Tildesley, an infectious disease modeling expert at the University Warwick and a UK government scientific adviser.

“They need to look at the European situation, and I mean, by no means what we have done in Europe is perfect, these governments are probably reacting a little bit slowly, but they are at least reacting, they are doing what they can to make sure that health services are not overwhelmed… and I think this is clearly what’s needed in the US.”

The Czech Republic is a good example. After a very mild spring epidemic, the country relaxed most of its coronavirus restrictions over the summer, ditching compulsory masks and fully reopening the economy.

When cases started rising again in September, the government resisted calls from scientists that tougher measures were needed. By mid-October, the central European country became the world’s worst-affected nation, reporting more new Covid-19 cases per million people than any other major country. The government then said it had no other option than to impose a strict mask mandate and shut down, otherwise its hospitals would likely run out of beds.

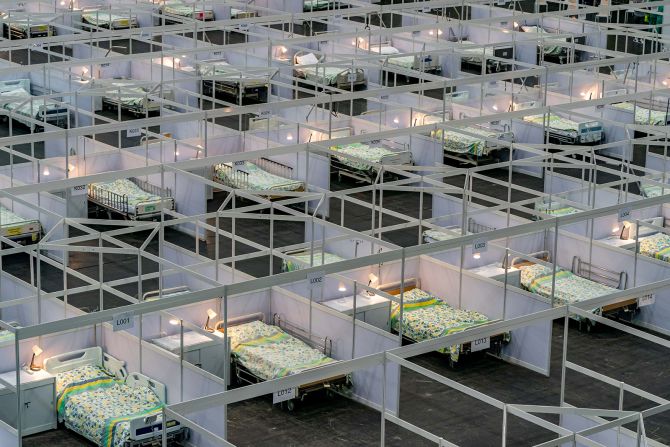

Four weeks later, the country is seeing dramatically lower numbers of new infections. While the health care system has been stretched well beyond its limits – the country was forced to deploy teenage nursing students in some hospitals – there seems to be light at the end of the tunnel.

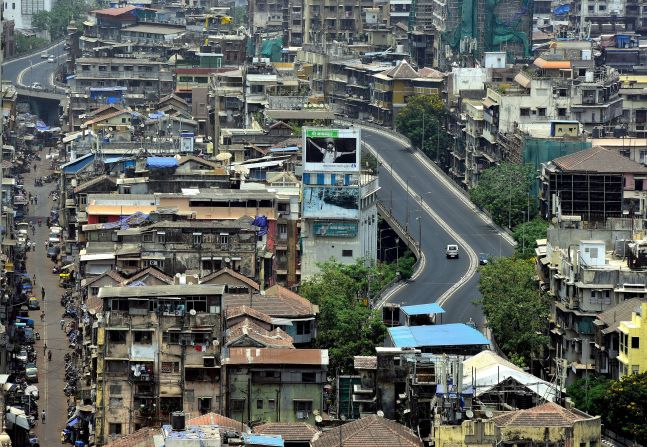

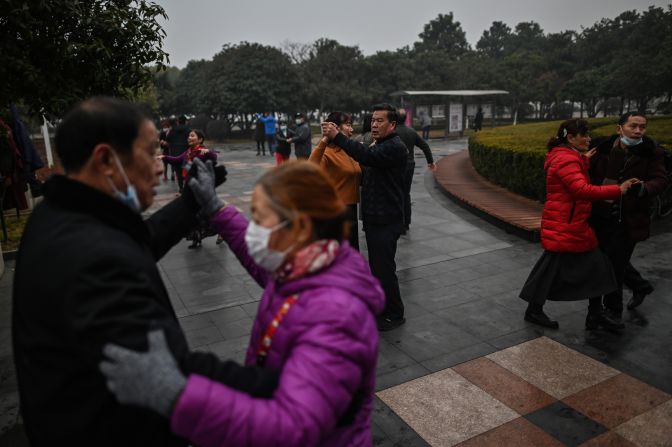

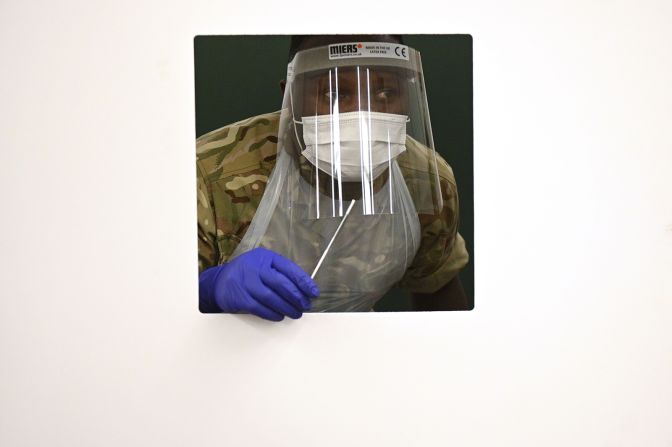

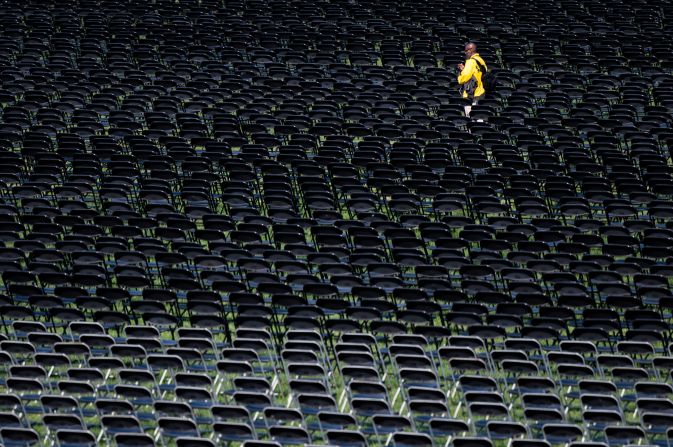

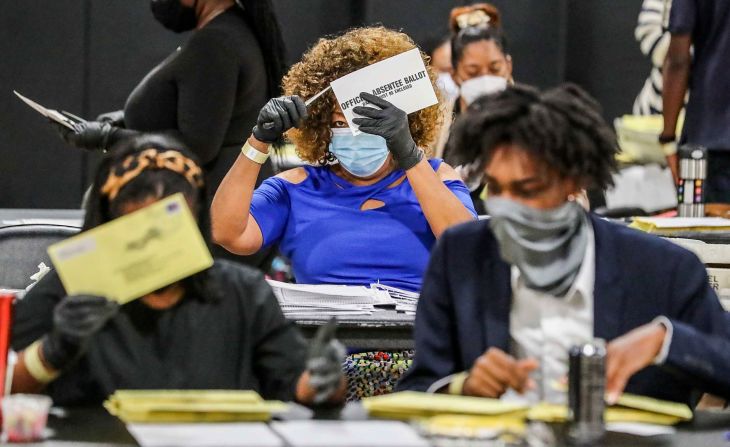

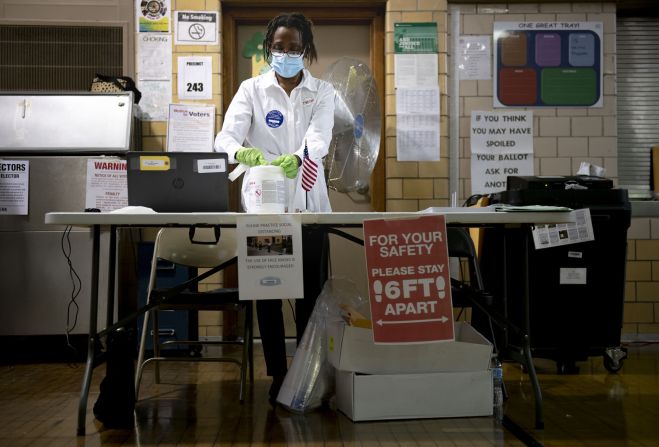

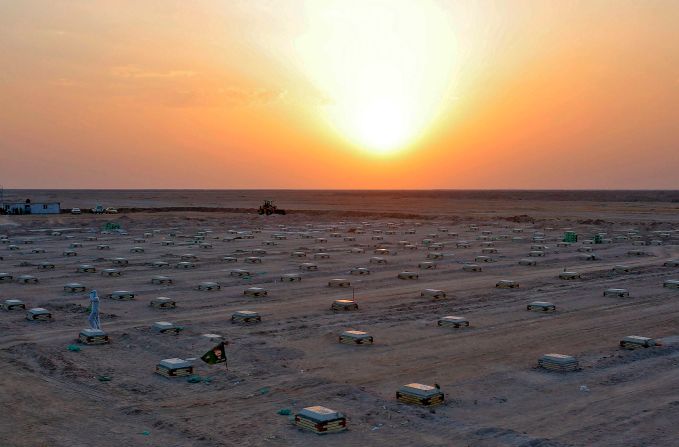

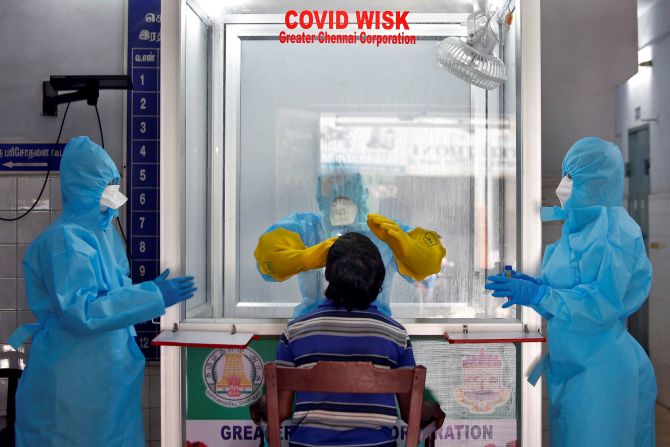

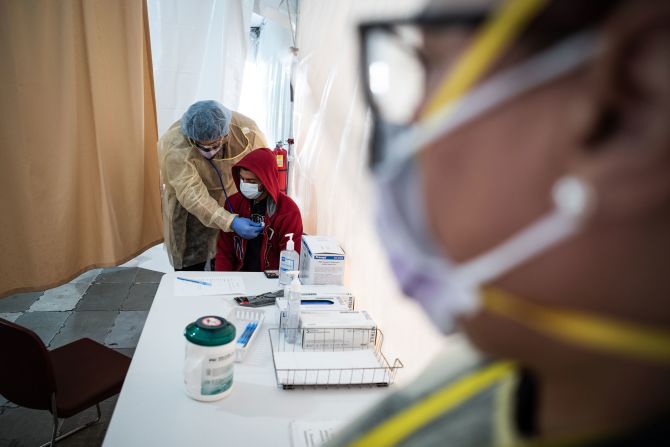

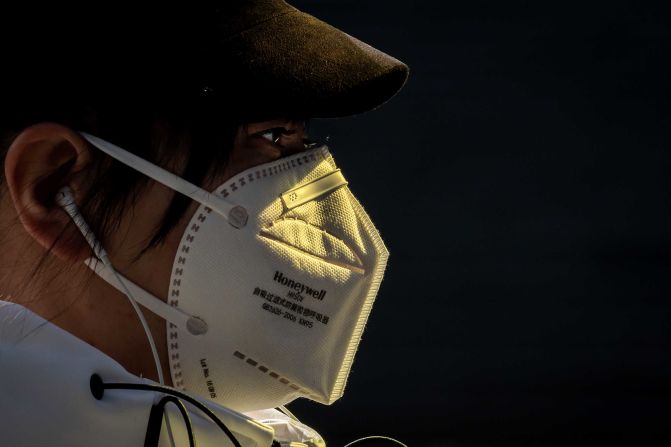

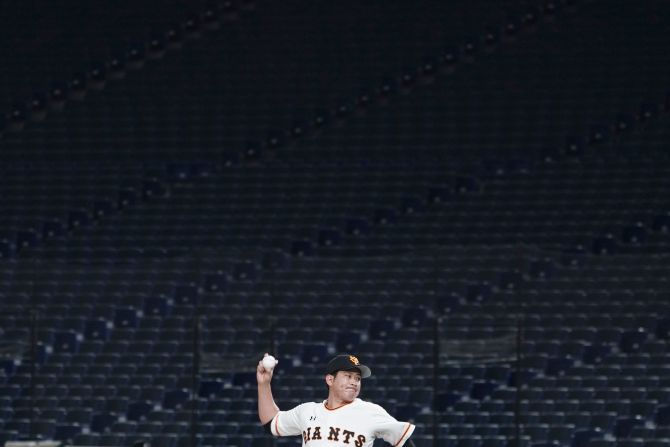

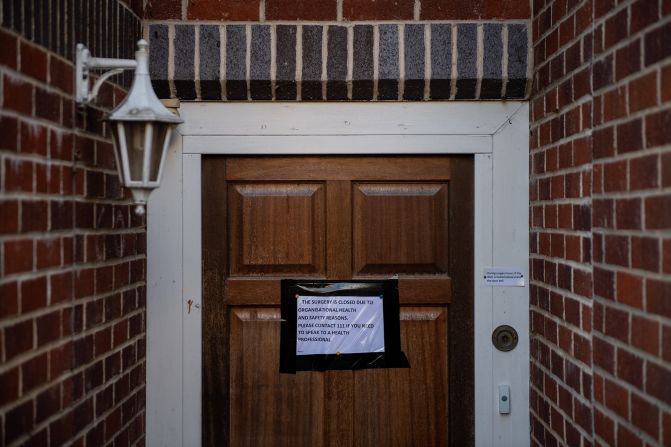

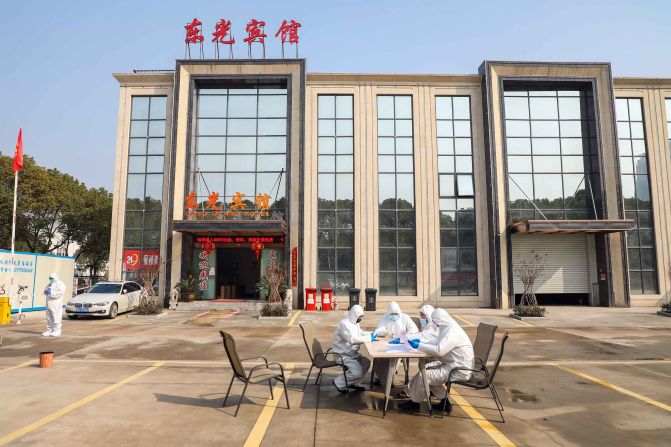

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

But according to official data, around 25% of ICU beds and 45% of ventilators remained available in the Czech Republic, even during the worst of the crisis. Compare that with US states like Oklahoma, where only 6% of ICU beds remain available. The number of cases in the state is rising exponentially – yet it has put in very few measures to limit the spread of the disease.

Starting Thursday, bars and restaurants across the state must maintain a six-feet distance between tables, but can remain open for in-person services until 11 p.m. – in much of Europe, indoor dining is completely off the menu.

Research from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has linked eating at restaurants to higher Covid-19 risk. But when Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer banned indoor dining in an attempt to curb the rising spread of the virus, White House coronavirus task force member Dr. Scott Atlas criticized the move and urged people to “rise up” against the new public health measures.

Tildesley said one problem is that the rules across different US states remain inconsistent. “The country is so vast and population density in Nebraska is not the same as New York State for instance or California, so you maybe do need to think about slightly more local action, but the issue is that really those decisions should be made based upon the epidemiology not based upon the political inclinations,” he said.

Not all lockdowns are created equal

Many European countries followed in the Czech footsteps by initially refusing new lockdowns and then going for the nuclear option. Germany and France both announced new national restrictions within hours of each other on October 28.

France began its strict lockdown on Friday, October 30, with people banned from leaving their homes without a special certificate. By November 16, the French Health Minister Olivier Veran declared the worst to be over.

“Over the last 10 days, there’s been a decrease in the number of new Covid-19 cases, and the positivity rate has been declining so everything suggests that we have passed a peak of the epidemic,” he said during an interview with regional press group Ebra on Sunday.

“It is the fruits of [the French] labor and a result of the measures we have taken to achieve this,” Veran said, adding that the positive development doesn’t mean the country has defeated the virus yet.

Germany, meanwhile, took a softer approach to lockdown. It closed restaurants, bars and clubs, but shops remained open and people were only advised, rather than ordered, to stay home and limit their social contacts.

The country didn’t see the same slowdown in new cases as France. German Chancellor Angela Merkel said this week that the situation in her country was still “very serious.” She pushed for a stricter set of nation-wide restrictions, but was unable to get enough support for that measure from state governments. On Friday morning, Germany reported a new record number of daily coronavirus infections over the past 24 hours.

The success of a lockdown also depends on the willingness of people to follow the rules. “If the rules are very very strict, then it’s a lot harder for people to sort of ‘get around’ those rules and if the restrictions are a little bit more mild, then it opens the floodgates potentially for people to be not compliant by the rules,” Tildesley said.

Germany and France were seeing similar spikes in their reproduction number in mid to late-October. Known as R, the number indicates how many other people each infected person passes the virus onto – in this case, both France and Germany reported the number went as high as 1.5.

After the lockdown went into effect, France’s R rate fell significantly, dropping below 1 – a crucial level that indicates the epidemic is shrinking – on November 6 and dropped further since then, according to data from the French Public Health Agency. In Germany, meanwhile, the number has dropped to 1, but continued to hover around that level, according to the Robert Koch Institute, Germany’s Center for Disease Control.

But while R is useful, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Dr. Oliver Watson, an infectious diseases researcher at Imperial College London said that another reason why France is seeing a reduction is because the country had a much higher transmission rate to start with.

“This includes the much larger first wave but also their second wave started taking off earlier, most likely because their infection levels were larger during the summer,” he said.

Watson and his colleagues at Imperial modeled the impact of lockdowns of various lengths and strengths on ICU capacities in Germany, France and Italy and found, broadly, that from an epidemiological point of view it is more beneficial to impose lockdowns early, rather than wait and then make them last longer.

Germany had also experienced a milder first wave of the virus, meaning there might be more people still susceptible to it.

Lessons not learned

The problem: despite their earlier experiences, many governments are still making decisions based on politics, not science.

“I remember the situation with the Czech Republic, that was an indicator that other countries needed to be on guard and start to prepare for early controls … and we can go back to the first wave and we can again see that there were early warning signs that we needed to consider greater controls and they were there probably about two weeks before the [UK] government introduced lockdown,” Tildesley said.

Politicians are reluctant to impose lockdowns because of their undeniable negative effects, be it on the economy or people’s mental health. But scientists like Tildesley say the repeated European experience shows the effect of this is even more damaging.

“It’s essentially Groundhog Day,” he said. “The scientific community is pushing for this and by the time the governments decide, it’s two to three weeks after we were pushing for it and the waiting makes it much worse. Lessons really, really do need to be learned.”

CNN’s Saskya Vandoorne in Paris contributed reporting.