Joe Biden was hours away from winning the job he had always wanted, but inside his corps of top advisers and close friends, planning was already shifting past the fireworks and confetti cannons used to celebrate his victory and back to the issue that could define the highpoint of his long career: The coronavirus.

As votes continued to be counted last week and the likelihood of him defeating Donald Trump rose, Biden was acknowledging privately to friends and advisers that much of what he wanted to accomplish as president would have to take a back seat – at least initially – to the pandemic.

After his projected victory on Saturday, he moved quickly to turn his focus from the presidential campaign to the pandemic, taking his first action as President-elect by naming a 13-person coronavirus task force and addressing the American people about his plans to control thee pandemic.

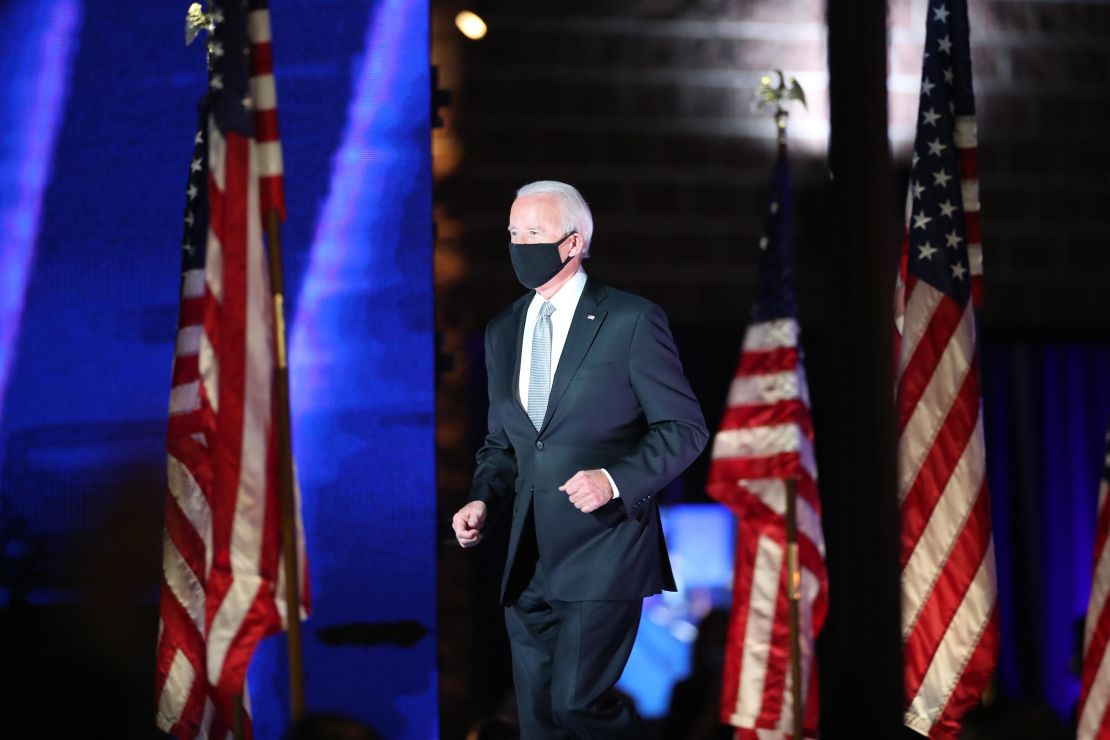

“This election is over,” Biden said Monday, before imploring Americans to wear a mask. “Do it for yourself, do it for your neighbor. A mask is not a political statement, but it is a way to start pulling the country together.”

Biden plans to privately reach out to Democratic and Republican governors during the transition to discuss coronavirus plans, aides said, and, when possible, talk with foreign leaders about what more the United States could be doing to combat the virus on the international stage. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called to congratulate him on Monday but soon found himself in a conversation about combating the virus.

Domestically, Biden is also interested in being part of the ongoing negotiations over the latest coronavirus relief package on Capitol Hill, a foray that could rekindle his relationship with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

“President-elect Biden is going to get to work right away to try to get relief for the American people. He won’t wait for Inauguration Day,” said Stef Feldman, one of Biden’s top policy advisers. “If there is something he can do to deliver, to help get relief to the American people, he will step up and do it.”

That outreach may now be fraught, however, given most leaders in the Republican Party – including McConnell – have given leeway to Trump’s evidence-free claims of widespread voter fraud.

Biden Transition

Entering the White House amid a global crisis is not unfamiliar territory for Biden, who entered the White House as vice president in 2009 as the country was sinking into an economic downturn that threatened to consume the Obama-Biden administration if they did not move quickly. Back then, like today, tackling the dominant issue was critical both because the country’s future relied on it and because the campaign was staked on exactly that.

Like 2009, there are also notable pitfalls for a Biden administration, including getting a possible vaccine out quickly, stimulating the economy enough to save small business across the country and getting governors and mayors to buy into plans for mask mandates.

“Moving as quickly and effectively as possible on the virus is not just symbolically important because he pegged so much if his campaign to it,” said David Axelrod, a top Obama campaign official in 2008, “but critical because the economy and so much else depends on it.”

Signs of coronavirus precautions on election night

Reminders of the coronavirus were all around for Biden aides as the results came in on Tuesday night.

A small cohort of the campaign’s top aides, led by campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon, were watching from a so-called “boiler room” inside the Chase Center on the Riverfront in Wilmington, taking in the results in real time and directing campaign strategy to aides spread across the country.

Wearing masks and separated by acrylic glass barriers, the top aides – along with some appearing virtually via video conference – watched as a series of mixed results came in.

And their superstition was on full display – in the form of a white sheet cake dotted with red and blue balloons that wished happy birthday to someone whose birthday was months earlier.

After Biden’s dismal finishes during the primary in Iowa and New Hampshire, Biden saw his standing improve in Nevada, placing second in the state’s caucuses on February 22 – a day that coincided with senior adviser Bob Bauer’s birthday. Following Biden’s better finish that night, the campaign started an inside joke that turned superstitious, ordering cakes with well-wishes for Bauer at their Philadelphia headquarters for each of the primary nights that followed.

Biden won them all and the tradition continued, ordering a white sheet cake on election night that read, “Happy birthday Bob! Many happy returns.”

Four days later, their superstition paid off. On Saturday morning, about half a dozen advisers were working in the boiler room when the race was called. While others were engaged in a conversation, Bauer — the supposed birthday boy — jumped up from his seat as he was the first in the group to see the alert that Biden had won.

Biden took it all in from his Delaware home in the nearby Greenville neighborhood of Wilmington, surrounded by family and friends, many of whom had been key to his political rise over the last three years.

And in yet another sign of how coronavirus had changed the election, Harris was not with Biden or the top campaign aides on election night, instead she spent the night with family and some top staff at the nearby Inn at Montchanin Village, a posh hotel in the Brandywine Valley that that traces its name back to the Dupont family.

The Biden campaign had believed for weeks that election night would play out as a series of vignettes, each one causing the emotions of agitated Democrats to ebb and flow. And the campaign hoped that a memo in October, which cautioned Democrats against believing the race would be a blow out, would be internalized.

But, in many corners of the party, that message was not heeded, as Democrats were in disbelief that anyone would back Trump after he mishandled the pandemic. Those feelings met reality on election night as early results out of Florida began to trickle out. The vote tallies showed the Biden campaign struggling to keep up with inroads Trump made in Miami-Dade County and sizable turnout in rural counties. Biden would eventually lose Florida, a state the campaign did not have to win. But the agita it caused among Democrats on Tuesday nightwas palpable.

Among Biden’s top aides, however, there was both a calm about how the night would play out and some impatience that it was taking a long time to count votes in states they correctly believed would end up in their column, like Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

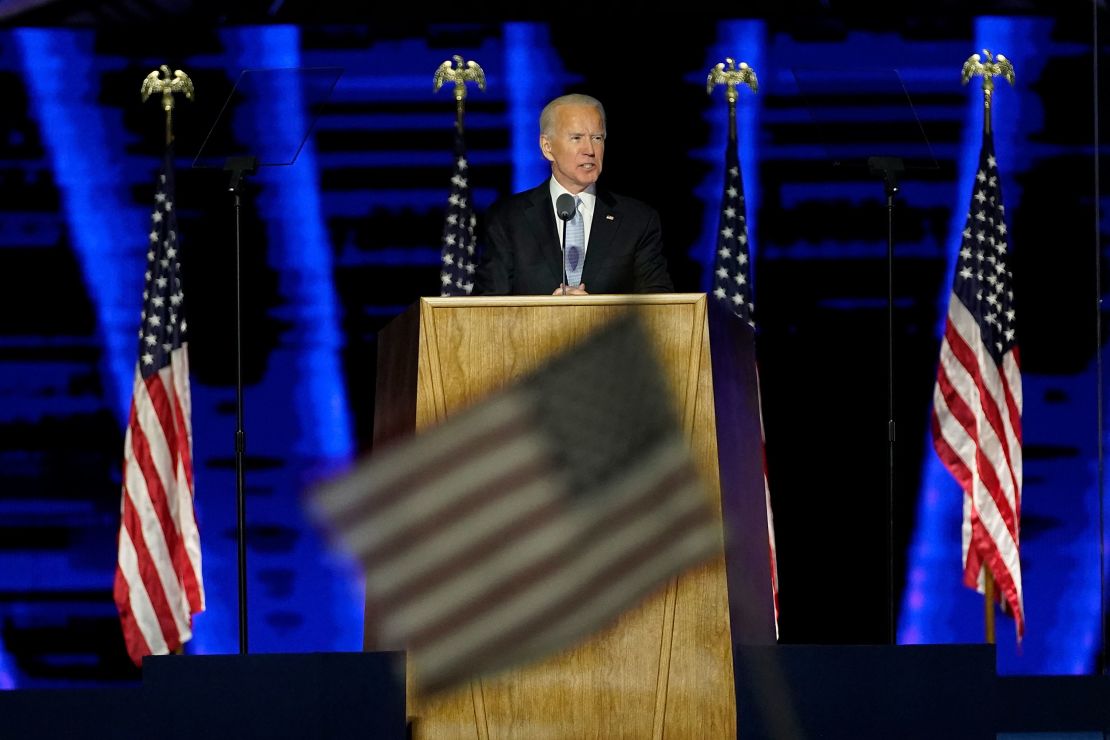

Biden, however, knew not to cede the moment to Trump, who had planned to speak from the White House, so the former vice president stepped in front of cameras outside the Chase Center – and dozens of honking cars – to project confidence.

“We feel good about where we are,” Biden said. “We really do. I am here to talk you tonight we believe we are on track to win this election.”

And that was true – there was certainty among Biden and his top aides – but it wasn’t until after 2 a.m. on Wednesday morning that the Biden campaign got solace from an unexpected place: The President himself.

Trump, when he eventually showed up at an election night party in the White House, appeared defiant but downtrodden. He accused Biden of “trying to steal the election” and claimed that he “won”, two lies that signaled to top operatives in the Biden campaign that Trump was flailing.

“It was not the speech of a confident man,” said a senior Biden aide.

Biden’s ‘mandate’: Curb the spreading virus

There are no signs that the virus will be in a better place once Biden takes over.

As the presidential election dragged on this week, the United States set three straight days of record coronavirus cases, each toping 100,000 new infections. The numbers, while providing Biden with a focus as he prepares to enter the White House, were also further proof that Trump’s claims the country was rounding the corner on the virus was a lie.

Biden, who has been stringently careful about contracting the virus, was notably calm all week as voted came in, leading friends and aides to quip: The former vice president had waited over three decades and two failed campaigns to celebrate the moment he would accept the nation’s top job, so what was a few extra days?

And as the week wore along, aides say, Biden was far more patient than many of his family, friends and supporters, who were desperate to hear that victory was certain.

While Biden launched his campaign on a pledge to restore the soul of the nation, another burning quest for him was to restore the nation’s image around the globe, where he spent much of his long career hopscotching from country to country as a leader of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and as Vice President. Since the very moment he heard Trump deliver his “America First” agenda, he told friends, worried about the United States’ standing with allies.

But both of those goals would have to wait.

Biden has increasingly known, as cases of coronavirus kept on an upward climb, that his marching orders were clear.

Getting the nation to return its focus to fighting Covid-19 was his leading priority, he told allies, which would set the course of his presidency. The challenge seemed more dire and urgent with each passing day, although aides said that he and his team were heartened by exit polls on election night that showed 67 percent of voters believed wearing masks was a public health responsibility, compared to 30 percent who called it a personal choice.

So even as ballots were being counted in battleground states across the country, Biden’s team was eager to show that he was on top of the coronavirus crisis. He could have been updated by Murthy and other experts on his team at his house, but aides wanted him to be seen going into The Queen theatre on North Market Street in Wilmington for a briefing on the pandemic and the accompanying economic crisis.

“We feel like that is why he will be president,” said TJ Ducklo, Biden’s press secretary. “We have a mandate to take bold action to get the virus under control. Even when the results were unclear, we still knew that more people than ever had voted for Joe Biden to be president, so we were bullish on that mandate.”

The contrast, which had been stark during his campaign with Trump, was even more clear in the days after the election. The president remained out of public view at the White House, not mentioning a word about coronavirus.

“With an all-time number of Covid cases, we did not see a thing about that from President Trump,” said Sen. Chris Coons, a Delaware Democrat and longtime Biden friend. “But here we see Vice President Biden going to a detailed briefing for how to deal with a pandemic. That is his complete focus.”

The waiting

For many of Biden’s allies and aides, the slow trickling in of the vote tallies in the days after polls closed marked an agonizing waiting period.

“I don’t think anyone anticipated it would go until it did,” said one Biden aide. “I think by Friday, people were feeling like just, come on.”

The campaign became hopeful that a winner might be called on Friday, launching a frenzy of preparations around the stage set up in the parking lot outside of the Chase Center in Wilmington for a possible victory speech that evening. But when it dawned upon the team that that moment would not come on Friday, Biden delivered a late-night speech anyway.

While he stopped just short of declaring victory, the former vice president said this: “While we’re waiting for the final results, I want people to know we’re not waiting to get the work done and start the process.”

Biden advisers told CNN after the speech that that line was in large part a reference to the work that he planned to continue doing on the coronavirus pandemic. Regardless of where the vote-counting process was and until the 2020 race was officially called, advisers said Biden’s work behind the scenes on COVID – briefings, consultations with public health officials, etc. – would not slow down.

Looming over all of this, however, is the outstanding question of which political party will control the Senate next year – a question that will not be answered until after two separate Georgia Senate runoff races in January.

The very real possibility of Democrats remaining in the minority in the Senate has all but squashed hopes of a Biden administration pushing through ambitious and sweeping legislative items through Congress.

That prospect is shining a brighter spotlight on potential executive actions that Biden can take in the earliest days of his presidency, as well as the personnel appointments that he will make in the coming weeks, particularly on the economic front. There is also expected to be heightened interest in the hundreds of billions of dollars that were already set aside by Congress earlier this year for the Treasury Department and have not yet been allocated.

Democratic Rep. Josh Gottheimer, a co-chair of the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus in the House, told CNN that he had spoken as recently as Monday morning with a top Biden adviser who conveyed in no uncertain terms that the coronavirus recovery would be at the top of President Biden’s agenda.

The overarching message from the Biden team was clear: “We will be ready on Day One.”

Gottheimer acknowledged that how the control of the Senate ultimately shakes out will be “everything,” and that he is mentally preparing for another two years of a divided Congress. But he said that he was hopeful that Biden was better prepared than almost anyone else to inherit the challenges that come with a deeply divided Congress.

“To get Biden’s agenda done, we’re going to have to work together. Otherwise nothing will get done,” Gottheimer said. “You look at the history of how Biden has governed and reached across the aisle – he was specific in his (victory) speech about uniting. He didn’t come in with a partisan message. He came in with a unifying message. This is the way it should be.”