The record surge of early voting in Texas’ rapidly growing cities and inner suburbs, which on Friday helped power the state past its total votes cast during the entire 2016 election, likely marks the end of unchallenged Republican dominance in America’s second largest state – a seismic shift in the nation’s electoral landscape.

Even if President Donald Trump retains enough rural strength to hold Texas in Tuesday’s election, which many still consider the most likely outcome, the swelling voter turnout in and around the increasingly Democratic-leaning cities of Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio and Fort Worth points toward a return to political competition in the state after more than two decades of almost uninterrupted Republican ascendancy.

Just alone in Harris County, which is centered on Houston, nearly 1.4 million people had voted through Thursday evening, compared with 1.3 million total in the 2016 election. The state’s other big cities and inner suburban counties are experiencing comparable increases, with Texas’ 10 largest counties alone accounting for more than 5.3 million ballots cast through Thursday out of more than 9 million in the state.

“We expected a lot of turnout,” Lina Hidalgo, the Harris County judge (the equivalent of a county executive) told me. “We didn’t expect this level.”

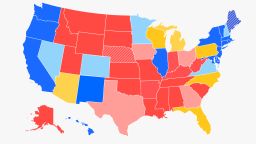

Texas 2020 presidential election polls

Some local analysts believe that with turnout cresting, and a recoil from Trump swelling Democratic support, Joe Biden could win the counties centered on those five big cities by more than a million votes combined – roughly double Hillary Clinton’s margin in them in 2016 and possibly 10 times Barack Obama’s advantage across the same places in 2012.

Whether or not Biden wins the state, or even precisely meets that prediction, a shift of anything approaching that magnitude would provide Democrats a formidable foundation from which to challenge the Republican hegemony over Texas – a foundation that will only grow stronger through the 2020s as these urban and inner suburban counties across what’s known as the “Texas triangle” drive the vast majority of the state’s population and economic expansion.

“If the explosive growth in the urban centers and suburbs continues [for Democrats] that will be the whole ballgame,” says Richard Murray, a longtime political scientist at the University of Houston who has forecast the 1 million vote metro advantage for Biden.

While Trump and other Republicans are consolidating crushing advantages in small-town and rural communities, Murray says, the stagnant or shrinking population in those places means Republicans “just can’t keep pace with this big [metro] vote.”

Republicans still have many advantages in Texas – particularly overwhelming support in its sprawling rural areas – and most observers consider Trump something between a slight and a substantial favorite to hold it.

New York Times/Siena College and University of Houston polls released Monday showed Trump leading by about 5 percentage points (though a University of Texas at Tyler/Dallas Morning News survey released Sunday gave Biden an edge). But the trend line in the state’s urban centers – a microcosm of the GOP’s retreat in big metro areas almost everywhere under Trump – is ominous for Republicans.

And the consequences of failure are almost unthinkable for them: Given the Democratic dominance of other large states – including California, New York and Illinois – there is no viable path for Republicans to win the White House without holding Texas and its 38 Electoral College votes.

Losing Texas – either next week or in 2024 – would register in Republican circles as a uniquely powerful earthquake that would rattle their confidence in the party’s direction and message, many GOP insiders agree.

A return to competition

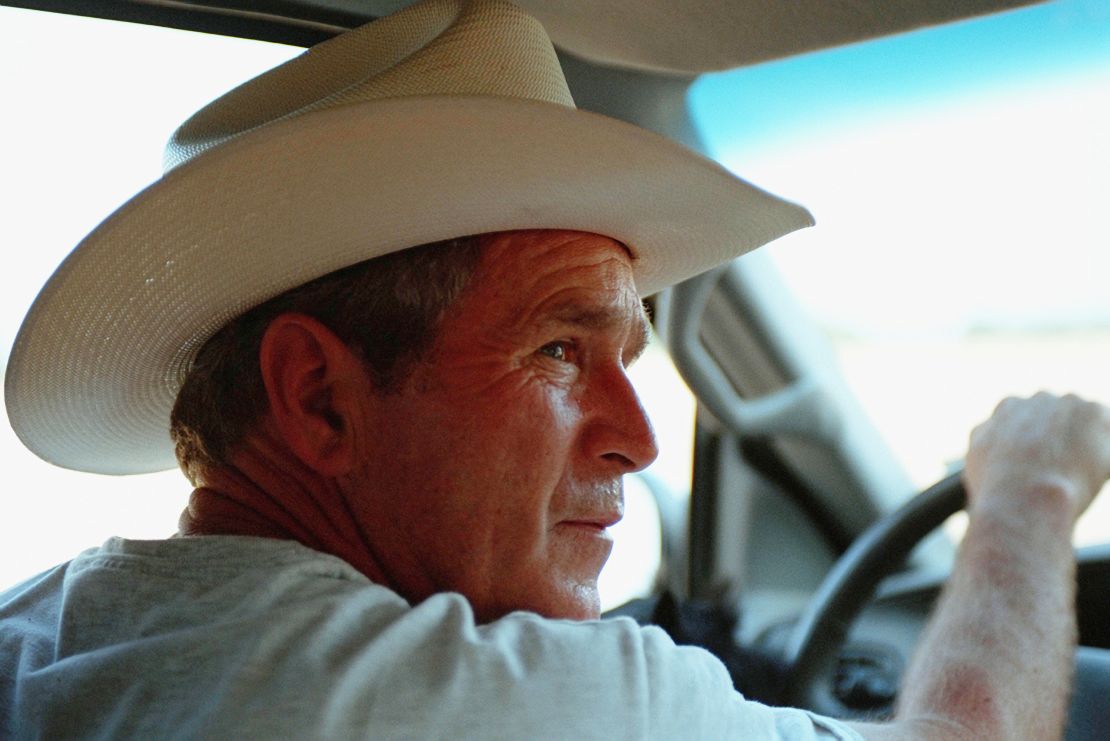

“Texas is in transition on steroids now,” Matthew Dowd, a former top adviser to Republican former Texas Gov. (and later President) George W. Bush, told me in an email. Dowd, who was earlier an adviser to top Democrats in the state, says that “Republicans will not be able to consolidate [control] again. The change is already past the point of doing that. They may still have slight advantage in 2022, but that advantage will dissipate in each year ahead.”

Bill Miller, a prominent Texas lobbyist and consultant who has also worked for politicians in both parties, says he believes Republicans retain an advantage in Texas for now, particularly if Biden wins nationally.

In that circumstance, he says, Republicans would benefit from less attention to Trump – who has repelled many suburban voters in Texas, just as in other states – and more focus on the agenda Biden will try to pass, particularly his push for higher taxes on high-income earners and corporations. That could help the GOP recapture some of the suburban White voters now rejecting Trump, he says.

More on Voting

But even with those potential tailwinds, Miller agrees that the days of impregnable GOP control over the state have likely ended.

“It’s never going to be the way it was,” Miller says. “Six years ago, Republicans looked at a seat, they won it. The only races were [the] Republican primaries: who could be the most conservative. That’s over. Now it’s very competitive. It’s not that Republicans have all the money and good candidates and Democrats don’t. Now they have money and good candidates too. It’s all in.”

Even if Biden doesn’t win the state, a commanding showing in the metro areas could lift Democrats seriously competing for as many as half a dozen Republican congressional seats and bidding to flip enough seats in the state House of Representatives to regain control of the chamber for the first time since 2002.

The New York Times poll released Monday showed Biden leading Trump across the 12 mostly suburban Texas congressional districts considered most competitive, terrain that almost entirely overlaps with the seats Democrats are contesting in the state Legislature. The University of Texas poll likewise showed Biden leading Trump in all four of the state’s major metropolitan areas.

A new era of political competition in Texas would mark a back-to-the-future trajectory for the state. Like most Southern states, Texas, which seceded to join the Confederacy, unflinchingly supported Democrats for most of the first century after the Civil War. Although Republican John Tower broke through to win a Senate seat in 1961 (replacing Lyndon Johnson when he became vice president), the GOP didn’t really establish a beachhead in the state until Republican Bill Clements won the governorship in 1978.

The next 16 years offered the longest period of sustained political competition in the state’s history. The two parties alternated winning the governorship in the four elections from 1978 through 1990 (starting with Clements and ending with tart-tongued Democrat Ann Richards), and while Republicans easily carried the state in each presidential election over that period, Democrats maintained control of the state Legislature and US congressional delegation.

Over this era, the Republican coalition was centered on suburbs filled mostly with White voters who had joined a “White flight” exodus from cities as minority populations grew and who remained intently hostile to taxes. Democrats relied on a big urban vote combined with support in rural areas with voters whose ancestral loyalties to the party were so great that it was said they would vote for a “yellow dog” before a Republican (at least in state races).

“Historically, this is really hard to understand, the rural areas had been the base of the Democratic Party,” says Garry Mauro, a Democrat who served as the state’s elected land commissioner from 1983 through 1999. “The Republicans carried Dallas and Houston and Austin.”

That competitive balance collapsed in 1994. In the backlash that developed – especially across the South – against Bill Clinton’s chaotic first two years as president, Bush ousted Richards as governor that year, even though she remained personally popular. Democrats have not elected another Texas governor since.

Mauro was part of a class of tough and salty Texas Democrats (including Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock and state Comptroller John Sharp) who held their statewide offices against the Republican tide that year. But Bush and his political consigliere Karl Rove solidified Republican dominance over the state.

In 1998, Republicans – with candidates including Rick Perry as lieutenant governor and John Cornyn as attorney general – swept to control all of Texas’ statewide offices, including the governorship, when Bush soundly defeated Mauro, the Democratic nominee, for reelection. Democrats have not won any Texas statewide office since.

Over the next few years, Republicans gained unified control of the Texas Legislature and haven’t surrendered that since either, in part because of aggressive gerrymanders. Republicans have controlled a majority as well of the state’s US congressional delegation since early this century and have held both US Senate seats since 1993 (when Lloyd Bentsen resigned to serve as Clinton’s treasury secretary).

Factors for change

For roughly two decades, from 1998 until the 2018 election, Texas Democrats faced what Mauro called a “bleak” landscape. With unified control of state government, Republicans fortified their position not only through the aggressive gerrymanders, but also by passing a series of laws that made it more difficult to register or to vote, including one of the nation’s toughest voter identification laws. One comprehensive academic study recently labeled Texas as by far the state in which it is most difficult to vote.

Long-term and near-term factors have combined to scramble this equation – and to do so, as Mauro says, “faster than I thought, and I’ve been preaching it.”

The most visible long-term change in the state has been its growing racial and ethnic diversity. With the Hispanic and Asian American populations growing particularly fast, people of color have increased from 34% of the Texas electorate in 2004 to a projected 40% this year, according to forecasts from the nonpartisan States of Change project.

Less visible but also critical has been the shift of the state’s population, economic activity and voting totals to the state’s metro areas. The so-called “Texas Triangle,” which extends from Houston in the Southeast to San Antonio in the Southwest and then north through Austin and Dallas/Fort Worth, accounts for more than 7-in-10 of the state’s jobs and about three-fourths of Texas’ economic output.

These prospering cities – and the rapidly growing suburban counties around them, such as Collin and Denton near Dallas, Williamson and Hays around Austin and Fort Bend outside Houston – have become a magnet for well-educated transplants from other states, such as California and New York. The Census Bureau recently reported that the Texas Triangle accounted for fully 6 of the 10 counties nationwide that added the most population in the past decade.

The Texas Triangle “is where all the population growth, all the job growth, all the talent is, where all the Californians are moving,” says Steven Pedigo, director of the LBJ Urban Lab at the University of Texas at Austin. “Texas is growing, but it’s all in metro. It’s not in rural anymore; rural population is declining. It is a metro state.”

Murray, the University of Houston political scientist, has chronicled the impact of this population shift on the state’s voting patterns. Murray and colleague Renee Cross calculated that in 1980, the 27 counties in the metropolitan areas centered on Houston, San Antonio, Austin and Dallas/Fort Worth cast about 55% of the state’s votes. By the 2018 election, that number had soared to 69%. Over that same period, the share of the vote cast in the 28 largely Hispanic southern and western Texas counties drifted down slightly from 10% to just below 8%.

The big change came in the state’s 199 non-urban counties, which have become the foundation of the Republican Party: They’ve fallen from about 37% of the vote in 1980 to just over 23% now.

For years the political impact of this population shift was muted because Democrats did not make gains in the Texas suburbs comparable to their breakthroughs since the early 1990s in demographically similar communities elsewhere. More college-educated suburbanites in Texas than elsewhere are conservative on both social and fiscal issues, in part because a much greater share of them than in Northern suburbs are evangelical Christians. Largely as a result, Republican presidential nominees carried the full 27-county metro area, which comprises cities and their suburbs, in every presidential election from 1968 through 2012, according to the Murray and Cross study.

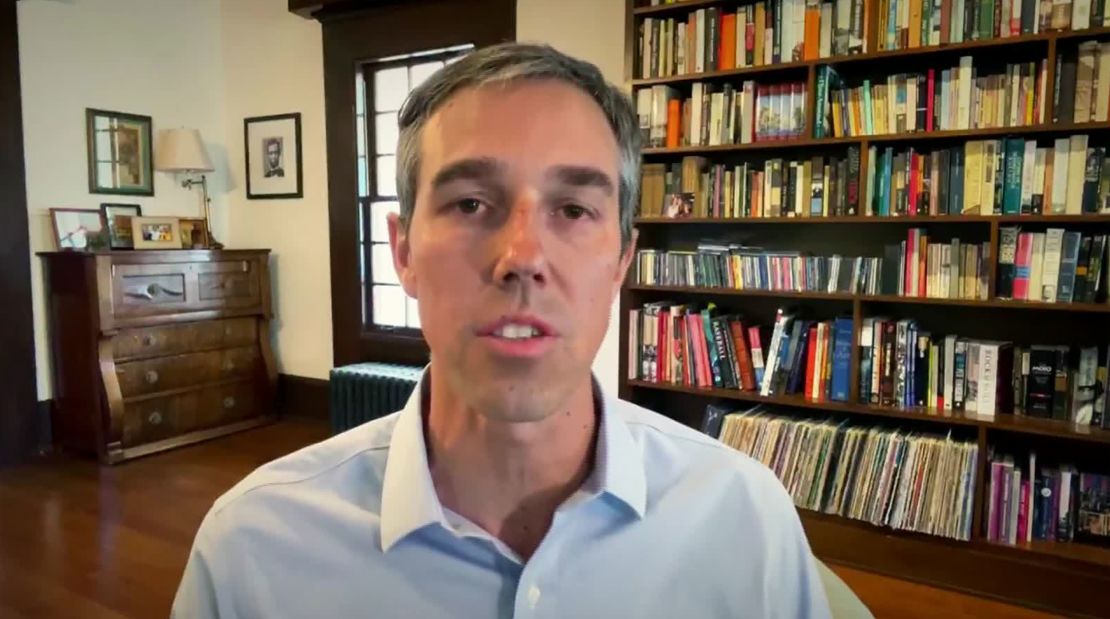

But once Trump became the GOP’s face, the Republican hold on the Texas metros loosened. Hillary Clinton narrowly outpolled Trump across the full 27-county area. Two years later, Democratic former US Rep. Beto O’Rourke, in his narrow Senate loss to Republican incumbent Ted Cruz, blew past Clinton’s markers. O’Rourke won nearly 55% of the vote across the full 27-county metro region and became the first top-of-the-ticket Democrat since favorite son Johnson in 1964 to win each of the state’s four large metropolitan areas.

Democrats’ growing margins

The change is even more apparent when looking at the five core urban counties inside the burgeoning Texas Triangle: Harris (Houston), Dallas, Travis (Austin), Bexar (San Antonio) and Tarrant (Fort Worth). In 2012, Obama won all of them except Tarrant but by a modest combined margin of about 130,000 votes. Four years later, Clinton again won all of them except Tarrant, with a more robust margin of 562,000 votes. Then in 2018, O’Rourke won all five of the core urban counties by a combined total of 790,000 votes – six times as much as Obama’s advantage only six years earlier. Whereas Obama won Harris County by 1,000 votes and Clinton by 162,000, O’Rourke pushed the margin to 200,000 votes.

Early voting has exploded across all of these metro areas in 2020. Harris County has seen an especially dramatic outpouring. Hidalgo, a 29-year-old Democrat and immigrant from Colombia who ousted an older White Republican in 2018, says that in 2016, the county invested $4.1 million to run the election.

This year, the county increased that to $31 million, funding an extensive array of innovative measures that have eased access to the polls, from expanding early voting sites and keeping them open longer to allowing drive-thru voting and even holding a 24-hour voting session later this week. In the process, Harris County has become a powerful example of what voter participation might look like if governments affirmatively make voting more accessible.

Build your own road to 270 electoral votes with CNN’s interactive map

“If you build it, people come, and we have lowered the barriers to entry, to safe, secure election,” Hidalgo told me. “We see that when you lower the barriers, it wasn’t that people were apathetic – they were ready to participate – but it was hard [to vote].”

With the county poised to soon surpass its total 2016 vote, Hidalgo says it’s not unreasonable to ask how close it can come to the total voter registration of 2.3 million: “I don’t see why, with this energy, we can’t get as close as humanly possible to that full participation,” she says.

Likewise, Steve Adler, the Democratic Austin mayor, told me he expects record turnout there – in part because the county has registered an incredible 97% of its eligible voters. Enough of them may show up, he says, to push the county’s total vote this year up near 700,000, possibly 200,000 more than in 2016.

“That would be historic,” Adler says. “The number of people that are voting that are young is just incredible. We’re talking about over 35% of people voting in the city are under 40.”

Not only is turnout up in Texas’ core urban counties, but most observers also expect Biden to exceed Clinton’s vote share in them and to match or even surpass the elevated levels of support that O’Rourke achieved in them two years later.

As a result, Murray projects that Biden could win Harris, Travis and Dallas counties by at least 300,000 votes each – stunning numbers. Bexar and Tarrant (which Murray expects Biden to capture) could add another 200,000 votes to his pile. That could put Biden’s total lead from the five core counties at roughly 1.1-1.2 million, about double Clinton’s level.

The lingering Republican tilt in many of the suburban counties around this urban core will reduce the overall Democratic advantage in the Texas metro areas, but probably not by as much as in the past; Biden is likely to win several of the big Texas suburban counties (such as Fort Bend near Houston and Williamson outside Austin) and at worst significantly reduce the traditional GOP margins in several others (particularly Collin and Denton outside Dallas).

In all, Murray expects the 27 counties in the state’s four big metro regions to cast a record 70% of the total vote, and to provide Biden a margin of nearly 900,000 votes. He expects the largely Hispanic counties to add another 350,000 votes to Biden’s lead.

That might be a best-case scenario for the former vice president. But even if Biden doesn’t quite reach those numbers, the question will remain whether Trump can squeeze out enough votes from the remaining non-urban, mostly White counties. He won 75% of the vote in those places last time and Murray, like most observers, expects he will match or exceed that again.

What’s unclear is whether those counties can keep pace with the explosive turnout in the state’s urban centers. Murray thinks they won’t quite and their share of the statewide vote will slip to a little over 1-in-5, allowing Biden to narrowly capture the state.

Most others still give Trump the edge. Matt Mackowiak, an Austin-based Republican consultant, says it’s a mistake to assume the early vote totals guarantee the non-urban share of the vote will decline. Trump will pull out plenty of rural votes, he says.

“If you are analyzing data right now and rural voter is behind suburban and urban, I don’t think it means so much,” he says, since those non-urban voters are more likely to vote on Election Day than early. If anything, Mackowiak says, compared with 2018, “the rural turnout is going to be so much higher, because they connect with Trump in a way they don’t connect with Cruz.”

The hurdles that remain

While optimistic that Biden will post strong numbers in the metro areas, many Democrats say they would feel better about their overall Texas prospects if the former vice president’s campaign invested meaningful money in turning out voters in the predominantly Hispanic communities along the Mexican border, where participation historically runs low.

I spoke with O’Rourke on Saturday morning, when he was canvassing voters in Collin County, a diversifying Dallas suburb that may tilt away from Trump and the GOP this year.

“While you have a lot of concentrated spending in the Dallas/Fort Worth and Houston metro area because of competitive congressional and state House campaigns, there is a great opportunity for the Biden campaign to invest in the Rio Grande Valley, Laredo, El Paso,” he told me. “If you are looking at a neck-and-neck presidential race [in the state] that is going to be won perhaps at the margin you need a presidential campaign to spend in those [areas].”

Mauro is equally frustrated. “When people spend a billion and a half dollars and they can’t find money to spend in Texas, I’m sorry, that’s pure stupidity,” he says.

Beyond his choice to invest only modest sums there, Biden still faces formidable hurdles to capture the state this year. Mackowiak says the deep ideological contrast visible in the presidential race, around issues from taxes to the Supreme Court, may allow Trump to regain some college-educated suburban voters who drifted away from Cruz in 2018. (While Biden may reach 60% support from college-educated Whites in states such as Pennsylvania and Colorado, the latest polls released Monday show him still stuck in Texas well below the 44% of them O’Rourke carried.)

Even Democrats acknowledge that Biden’s pledge at last week’s debate to eventually “transition away” from the use of oil may hurt him in midsized Texas cities that have become dependent on oil services – though the state’s overall reliance on oil jobs has significantly diminished, and Biden’s focus on climate change could help encourage more youth turnout.

Turnout in the Hispanic counties may not reach the level Democrats need as well – and, while media polls often have difficulty accurately measuring Hispanic sentiment, Monday’s surveys also showed Biden failing to match Hillary Clinton’s margin with those voters.

But if Biden wins the presidency with or without Texas, expanding the Democrats’ beachhead in the Lone Star state – with an eye toward fully contesting the state in 2024 – would surely rank among the party’s highest political priorities.

State Republicans may be creating an opening by emulating Trump in running against, rather than trying to court, the state’s thriving metropolitan centers: In the past few months, Gov. Greg Abbott has overridden local mask ordinances from Hidalgo and others (though he later changed course to order mask-wearing when coronavirus cases spiked), forced cities to reopen more widely than they wanted during the pandemic and threatened to somehow seize control of Austin’s police force because he opposes funding decisions the City Council has made.

The outgoing Republican speaker of the state House, from a small town at the edge of the Houston area, was secretly recorded telling a conservative activist, “My goal is for this to be the worst session in the history of the Legislature for cities and counties.”

The state’s GOP leaders have pursued “a shortsighted and destructive” posture toward the cities, says Adler. “Until we start having statewide Democratic leaders, who is the foil for Republican leadership? The foil in that situation is going to be cities. It used to be just Austin, and obviously we’re still bearing the brunt, but it’s more than just us.”

Adds Hidalgo: “The leadership of the state has made a political calculus they would rather pander to a certain extreme than deliver to these urban areas.”

With their decision to frame cities as a threat to their rural and small-town base, the Texas GOP leaders are closely following Trump’s tracks. And huge margins in the preponderantly White and socially conservative rural strongholds, as well as incremental improvement among Hispanics, may indeed allow Republicans to hold the state in the 2020 presidential race and maybe the governor’s contest that follows in 2022.

But it’s not difficult to forecast that the party’s prospects will steadily dim through the 2020s if it cannot reverse its erosion in the diverse urban and inner suburban counties growing inexorably in both economic clout and voting numbers.

If that happens, the GOP hold on Texas will become the biggest casualty of the trade Trump has imposed on his party of attempting to squeeze bigger margins out of small-town and rural communities that are shrinking at the expense of provoking greater opposition among cities and inner suburbs that are growing.

“There is obviously huge risk there,” says Mackowiak. “You get to a point to where the math doesn’t work anymore. I don’t think we’re there, but you can see the light at the end of the tunnel and it’s not daylight. It’s a train coming to run you over.”

This story has been updated with early-voting figures for Texas as of Thursday night.