There may be more water on the moon than previously believed, including on its sunlit surface. This water could be used as a resource during upcoming missions – like NASA’s return of humans to the lunar surface through the Artemis program.

The two studies published in the journal Nature Astronomy, and researchers shared their findings during a NASA press conference on Monday.

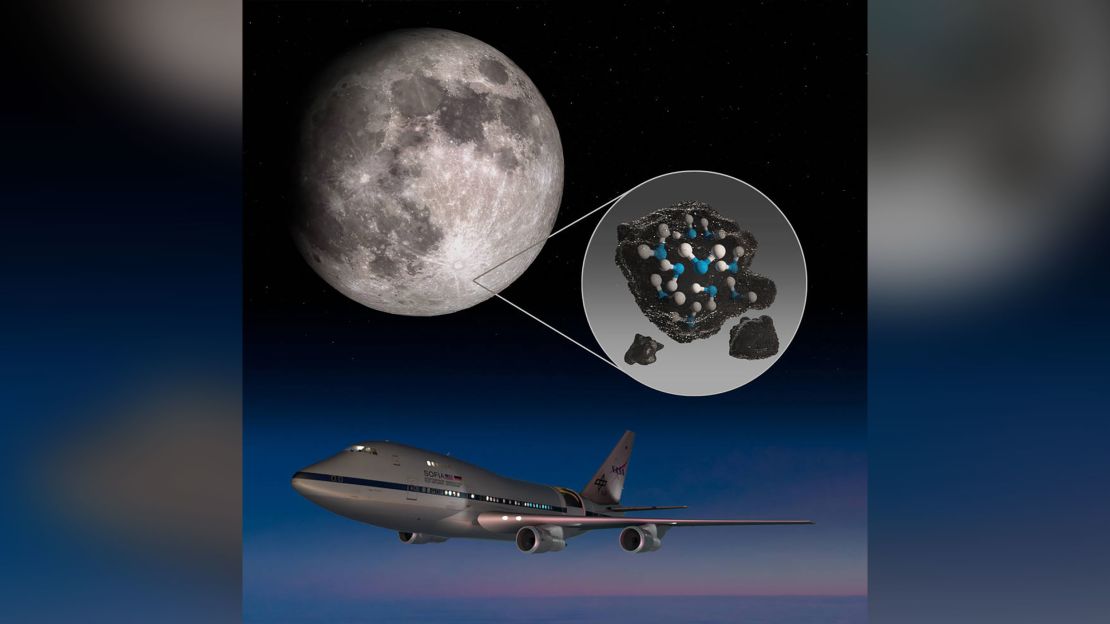

The research is based on data gathered by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, in orbit around the moon since June 2009, as well as the agency’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy airborne telescope, called SOFIA. The latter is a Boeing 747SP aircraft modified to carry a 2.7-meter telescope.

In the first study, researchers used SOFIA to observe the moon at a wavelength that revealed the signature of molecular water, or H2O.

“For the first time, water has been confirmed to be present on the sunlit surface of the moon,” said Paul Hertz, director of the astrophysics division at NASA’s Science Mission Directorate during Monday’s press conference.

“We had indications that H2O – the familiar water we know – might be present on the sunlit side of the moon. Now we know it is there. This discovery challenges our understanding of the lunar surface and raises intriguing questions about resources relevant for deep space exploration.”

Previous research revealed detections of water on the surface of the moon near the south pole. But the signature of molecular water at the wavelength used in this research could also be associated with hydroxyl, which is oxygen bonded with hydrogen. In organic chemistry, alcohols tend to include hydroxyl, which contributes to making molecules soluble in water. Hydroxyl is also an ingredient in drain cleaner.

The SOFIA detections confirm that water, not hydroxyl, can be found trapped in glass beads or in between grains on the moon at its high southern latitudes in Clavius Crater. This is one of the moon’s largest craters visible from Earth. There, water is present between 100 to 400 parts per million, or roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of water, according to NASA.

The fact that this water is inside grains or in between grains on the lunar surface helps protect it from the moon’s harsh and irradiated environment.

“Prior to the SOFIA observations, we knew there was some kind of hydration,” said lead study author Casey Honniball in a statement. “But we didn’t know how much, if any, was actually water molecules – like we drink every day – or something more like drain cleaner.” The published study captures the results from Honniball’s graduate thesis work at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa in Honolulu.

The water is trapped in a cubic meter of soil across the lunar surface.

The Sahara desert has a hundred times the amount of water than what SOFIA detected in the lunar soil, according to NASA. And the presence of this water raises questions about how it was created and how it even exists on the lunar surface.

The SOFIA telescope is able to fly at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet, which carries it above 99% of the water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere. This allows the telescope to see our universe in infrared light more clearly.

“Without a thick atmosphere, water on the sunlit lunar surface should just be lost to space,” said Honniball, now a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Yet somehow we’re seeing it. Something is generating the water, and something must be trapping it there.”

The water may be delivered by micrometeorites that land on the lunar surface and carry small amounts of water. Or solar wind streaming out from the sun could deliver particles and elements, like hydrogen, to the lunar surface. This could actually cause a chemical reaction with minerals that include oxygen in the soil. The reaction could create hydroxyl, which is then hit by micrometeorites to create water.

The SOFIA flight, which occurred in August 2018, was actually a test flight to see what kind of information the telescope could gather about the moon. The telescope is actually designed to look at distant objects.

“It was, in fact, the first time SOFIA has looked at the Moon, and we weren’t even completely sure if we would get reliable data, but questions about the Moon’s water compelled us to try,” said Naseem Rangwala, SOFIA’s project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, in a statement. “It’s incredible that this discovery came out of what was essentially a test, and now that we know we can do this, we’re planning more flights to do more observations.”

More SOFIA flights are planned in the future to follow up on this discovery and look for water in more sunlit spots on the moon. This will help researchers determine how exactly the water is created, stored and moves across the lunar surface. Understanding these processes of water on the moon will help NASA best determine how to extract that water for use as a resource.

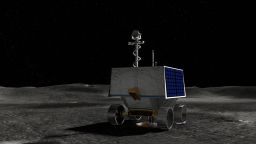

And NASA’s Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, or VIPER, will create the first water resource maps of the moon for future human space exploration once it lands on the lunar surface in 2022.

Ice-filled polar traps

In the second study, researchers used data from the lunar orbiter to study cold traps in permanently shadowed areas on the moon where water could remain frozen. Some of these cold traps may have evaded the sun for billions of years.

The most common hidden pockets of water across the lunar surface could be trapped in tiny penny-size ice patches that live in permanent shadows, the researchers discovered.

“If you can imagine standing on the surface of the moon near one of its poles, you would see shadows all over the place,” said Paul Hayne, lead study author and assistant professor in the Laboratory of Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, in a statement. “Many of those tiny shadows could be full of ice.”

After assessing the potential size of the traps, ranging from centimeters to kilometers, the researchers determined that permanently shadowed areas at both of the moon’s polar regions could contain a multitude of these “micro” cold traps. In fact, they could be hundreds to thousands of times more abundant than large cold traps.

The moon could contain 15,000 square miles of permanently shadowed traps in a range of sizes that could preserve water ice, the researchers estimated. Previous estimates have put the estimate at about half of that – at about 7,000 square miles.

“If we’re right, water is going to be more accessible for drinking water, for rocket fuel, everything that NASA needs water for,” Hayne said.

Previous searches for ice on the moon have been concentrated around the large craters at the poles, where temperatures have been measured as low as negative 405.67 degrees Fahrenheit.

Massive craters close to the lunar south pole include Shackleton Crater, which is several miles deep and about 13 miles across. And most of it is permanently in shadow.

“The temperatures are so low in cold traps that ice would behave like a rock,” Hayne said. “If water gets in there, it’s not going anywhere for a billion years.”

But these cold and dark environments are difficult to reach.

By using data from the lunar orbiter and modeling, the researchers determined that the lunar surface resembles that of a golf ball.

Of course, actual proof of these ice-filled shadowy pockets will require future digging by rovers or humans on the lunar surface.

But future missions to the moon, like landing the first woman and next man near the lunar south pole by 2024 through NASA’s Artemis program, could reveal more information.

Ahead of that, Hayne is also leading the Lunar Compact Infrared Imaging System, a NASA effort that will capture heat-sensing panoramic images of the moon’s surface near its south pole in 2022.

“Astronauts may not need to go into these deep, dark shadows,” Hayne said. “They could walk around and find one that’s a meter wide and that might be just as likely to harbor ice.”

Understanding how much water is on the moon will allow future missions to bring more equipment for science, rather than trying to transport water to the lunar surface – which is both heavy and expensive.

“Water is a valuable resource, for both scientific purposes and for use by our explorers,” said Jacob Bleacher, chief exploration scientist in the advanced exploration systems division for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, in a statement. “If we can use the resources at the Moon, then we can carry less water and more equipment to help enable new scientific discoveries.”