Hurricane Delta is the 25th named storm of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, and despite an already very active season, it is setting itself apart from the others in very big ways.

Let’s start at the beginning.

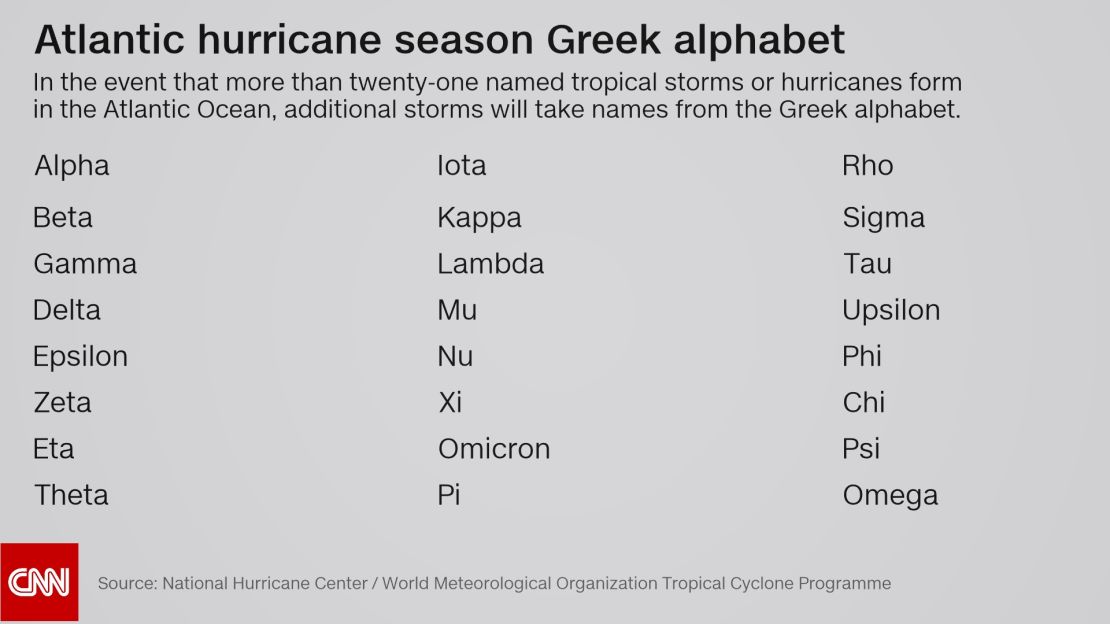

While “Delta” has been used once before, this is the earliest the Greek name has ever been used in a calendar year – more than a month sooner than on November 15, 2005. (And the Greek alphabet has only been tapped twice to name storms once a year’s entire list is used up.)

Get the latest news and forecast on Hurricane Delta >>>

Delta also grew from a tropical depression to a Category 4 hurricane in about 30 hours, with maximum sustained winds speeding up 85 mph in 24 hours from Monday to Tuesday. That’s the quickest increase in sustained wind speed in one day by a storm this year. (“Rapid intensification” is defined as an increase in top winds by 35 mph in 24 hours, and Delta more than doubled that.)

Delta is now the second-strongest storm of the year in the Atlantic Basin, only 5 mph behind Hurricane Laura, which reached 150 mph in the Gulf of Mexico. And when Delta strengthened to a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 145 mph, it cemented itself as the strongest Greek alphabet storm in history.

Delta’s current track has it heading northwest into the Gulf of Mexico late Wednesday, then turning due north as it approaches the US. Once it hits along the Gulf Coast, Delta will become the 10th named storm to make landfall this year in the continental US – the most in one year (after 1916, which saw nine landfalls).

Also notable is that Delta will be the fifth hurricane-strength system to make landfall in the US this year – the most since 2005 – after Hanna, Isaias, Laura and Sally.

Louisiana has taken the brunt of it. And if Delta crosses onto land as currently forecast, it will be the fourth named storm to make landfall in the Pelican State in 2020, a record for the most there in one season.

Location is everything for strong October storms

So far, this season has seen 25 named storms. The average for an entire season is 12. And before the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in August updated its forecast from 19 to 25 named storms in 2020, it had never forecast up to 25 storms in a season.

During an average season, about two named storms form in October and one in November. But this year is not a normal season. It has been forecast for months to be very active, and every named storm so far this season except three (Arthur, Bertha, and Dolly) set their own record for the earliest named storm ever recorded.

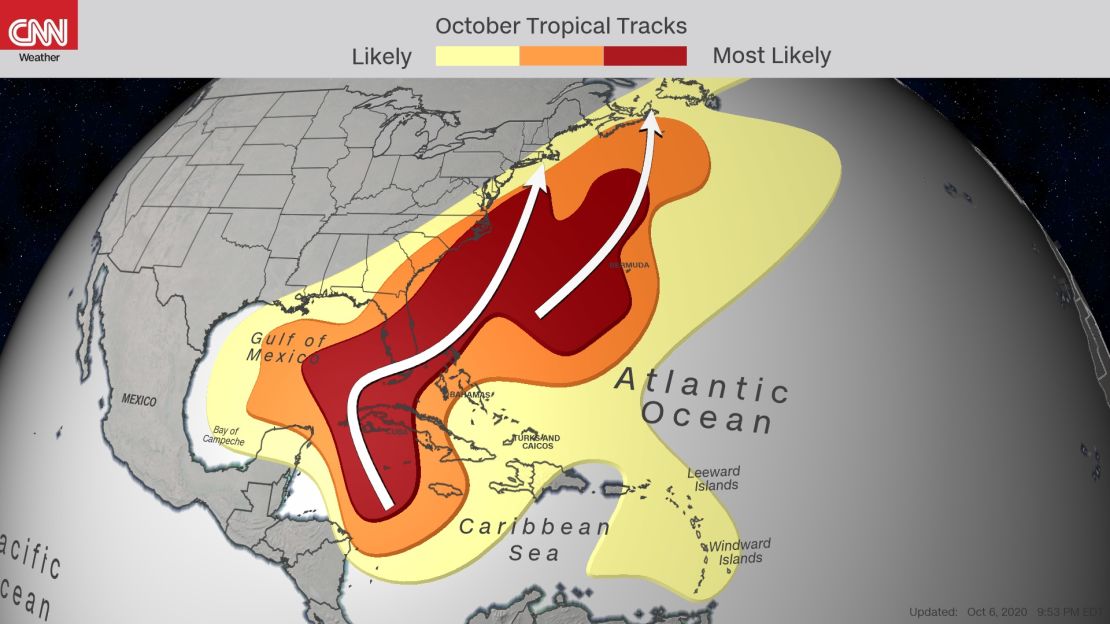

If a storm is going to form in October, the most ideal typically conditions exist in the northwestern Caribbean Sea. From there, storms usually head north toward the Gulf of Mexico or northeast along the eastern US coast.

“Tropical cyclones need favorable conditions to form, which are low wind shear and warm waters,” CNN meteorologist Michael Guy said. “As we transition to winter, these areas of opportunity narrow considerably.

“The push of cold air from the north and the waves in the jet stream allow this to happen, which gives us strong wind shear,” he said. “However, there are still areas in the southern latitudes, namely around the western Caribbean, that have the right ingredients for these storms to develop quickly.”

Water temperatures are very warm here on two levels. Sea surface temperatures in this region are running around 2 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit above average right now. On a deeper level is the Ocean Heat Content.

“Ocean Heat Content is a measure of the available energy for a tropical system to use,” CNN meteorologist Taylor Ward explained. “It takes into account the depth of the warm water. If a system is moving over shallow warm water, it is easier to churn up cooler water and limit the intensification.

“Hurricane Delta has been moving through the highest Ocean Heat Content of the Atlantic, which resides in the northwestern Caribbean,” he said. “Values are … three to four times the amount needed to induce a significant increase in intensity, according to NOAA.”

That significant increase in intensity has already happened, and it’s because all those necessary components came together.

“Think of it like baking a cake. You need to have all the right ingredients,” Guy said. “In the case of a tropical system, those ingredients are dynamical and thermodynamical – meaning wind and heat. However, just because you have the right ingredients doesn’t mean your cake/storm will always look like a perfect cake/storm. You also need the right conditions for them to develop properly. Otherwise, your cake won’t end up looking or tasting like a good cake. “

It has happened in the past, too. In fact, this region is something of a rapid intensification hot spot for major hurricanes in October, including Michael in 2018, Wilma in 2005, Iris in 2001 and Roxanne in 1995. Michael was furthest north of these storms when it underwent rapid intensification, going from 40 mph at midday on October 7 to 75 mph about 24 hours later as it entered the Yucatán Channel.

All fourof those names have been retired because those storms were so deadly or costly that their future use would be “inappropriate for obvious reasons of sensitivity,” according to the National Hurricane Center.

Heading for the season record

Already very active, the Atlantic hurricane season does not end until November 30, and storms in some years have continued well after that. With nearly eight weeks left to go, the number of total storms is nearing the all-time record for one season, set in 2005 with 28 storms.

The season is also well above average already for Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE, which measures tropical cyclone activity, taking into account named storms, plus storms’ duration and intensity. Through October 6, the ACE measurement is usually around 87; this year, it stands at 113.

ACE does not take into account whether a storm makes landfall. This is important because it only takes one big storm to hit land to have widespread impacts. By the end of August, there were seven landfalling storms in the continental US – another record.

CNN meteorologist Brandon Miller contributed to this story.