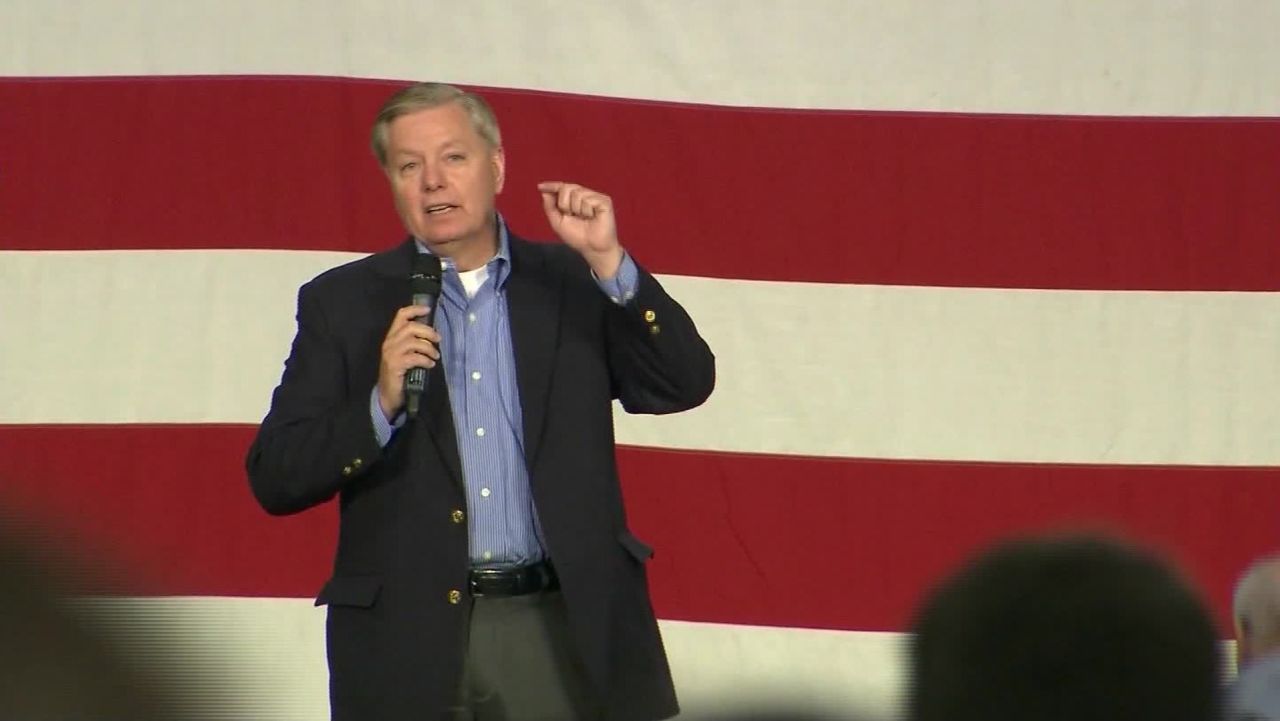

In four years, Sen. Lindsey Graham has gone from Donald Trump’s cutting critic to his dogged defender, a bipartisan dealmaker respected by Senate Democrats to a staunch conservative reviled by liberals across the country.

Graham has frustrated the left before but never paid the price in his red state of South Carolina. Now, the three-term senator is in the race of his life, facing an unexpectedly fierce challenge from his Democratic opponent, Jaime Harrison, whose insurgent campaign has raised and spent an unprecedented amount of cash.

The race is tied, according to three recent polls. But Graham is banking that South Carolina will send him back to Washington for three reasons: His alliance with Trump, his vigorous defense of the President’s Supreme Court nominees and push to confirm Judge Amy Coney Barrett before Election Day, and his opponent’s party ID.

In the final weeks of the campaign, Graham is attempting to mar Harrison’s hope-and-change message by tying him down to unpopular Democrats like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“Here’s what I’m gonna tell all the liberals talking about South Carolina: We’re gonna kick your ass,” Graham told a crowd full of police officers in Myrtle Beach last week.

Graham, who first came to power in Washington by winning a House seat during the Republican Revolution of 1994, had been viewed as a shoo-in for reelection for much of the cycle. But Harrison has swamped Graham across the airwaves, with $51 million in money already spent in ads and in future ad reservations – compared to just $18 million for Graham, according to Kantar’s Campaign Media Analysis Group.

“I’ve been helping Trump, and I apparently pissed every liberal in the country off,” Graham told CNN here in the state capital. “But we’ll be fine.”

Graham’s relationship with Trump is a double-edged sword. While Graham has earned many of the President’s supporters, it has also opened him to charges of hypocrisy, going from calling Trump a “race-baiting, xenophobic, religious bigot” in 2015 to telling CNN in an interview this past weekend that the two are “a team.”

“I don’t like it when people don’t have a stand on their issues,” said Maggie Parker, a voter in Columbia, when asked about Graham.

Even some of his supporters are critical of the shift.

“I’d rather him be honest and not flip-flop,” said Mike Jackson, a voter in Myrtle Beach who plans to vote the GOP line. “That’s one of the things I’m not crazy about. I like for a man to be straightforward and stay that way – not to turn out to be a yes man when his boss man turns up.”

In the interview, Graham was unapologetic about his shift, contending he has put his past disputes with Trump behind him.

“I accepted my defeat,” Graham said, referring to his loss in the 2016 Republican presidential primary. “President Trump won my state. I’ve been trying to help him where I can. He’s very popular in South Carolina.”

Graham also steered clear of any slight criticism of Trump. Asked about Trump’s own admission that he downplayed the coronavirus, held packed rallies during the pandemic, downplayed the wearing of masks and made repeated false claims that the virus would simply disappear, Graham instead defended the President’s actions.

“I think he made the decisions,” Graham said of Trump, pointing to restrictions on travel from China and ensuring ventilators were stocked up, a frequent argument made by the White House. “I don’t think you want to get out there and say, ‘Hey, the whole country is going to blow up.’”

Pressed on whether Trump should have held packed campaign rallies and crowded White House events, like the one announcing the nomination of Barrett to the Supreme Court where few wore masks or isolated themselves, Graham said: “People came, and I believe in wearing masks and they were social distancing.”

“It didn’t come out of Trump Tower; it came out of China,” Graham said of the coronavirus.

Similarly, asked if Trump has made his job harder – like after he failed to condemn white supremacists at last week’s debate – Graham didn’t answer directly.

“All I can say about people of South Carolina is it’s not the color of your skin,” pointing to Republican Sen. Tim Scott, a black Republican, and Nikki Haley, the former governor and daughter of Indian immigrants. “So, it’s not about where you’re from in South Carolina or the color of your skin, it’s about your ideas.”

Harrison’s plan: Rely on paid media

As he’s gained traction in the race, Harrison has taken an increasingly low profile, sparingly doing media interviews and steering clear of public events. As a father of two young children and a pre-diabetic, Harrison has been cautious during the pandemic, even insisting on acrylic glass to be placed beside him during Saturday’s debate and privately pushing for the debate to be held virtually up until the final hours before the event.

But it’s also unclear how Harrison fills his time. His campaign would not provide a list of virtual events his aides said he’s been doing, despite many requests by CNN. And he refused to agree to an interview or answer questions from CNN before and after his debate with Graham.

Many voters in South Carolina say they have seen a lot of Harrison – but only through his ads.

“They have been blitzing us with ads back to back on YouTube, Spotify, you name it,” said Lyric Swinton, a voter in Columbia. “It’s just about everywhere it’s ads all across the state.”

Harrison’s staggering spending prompts outside groups to jump in

Democrats haven’t had success in South Carolina ever since Fritz Hollings retired fifteen years ago after nearly four decades in the Senate. In the six Senate elections since 2004, the Democratic candidate never cracked 45% of the vote. But Harrison may break that barrier in his race against Graham, boosted by an unprecedented level of financial support.

In his final campaign in 1998, Hollings raised $5.6 million. Harrison’s campaign reserved more than that – over $9.3 million to be precise – in ads the week beginning October 6, according to CMAG. To date, the Senate contest is the most expensive in South Carolina’s history.

“Nobody’s ever had a race like this before,” said Walter Whetsell, a spokesman for the pro-Graham Security Is Strength PAC.

He said in South Carolina, statewide campaigns traditionally buy 8-10 weeks of television advertising at a cost between $2 million-$3 million dollars.

“He’s spending that damn near every two or three days,” said Whetsell.

Bombarded across the airwaves and facing tightening polls, Republican leaders are rushing to Graham’s defense.

The Senate Leadership Fund, the Super PAC aligned with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, has upped its plans to spend in the race, spending or reserving $9.6 million in South Carolina, compared to $6 million in advertising from the Senate Majority PAC, the Super PAC aligned with Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer, according to CMAG.

“The far-left money spigot has been turned on for liberal lobbyist Jamie Harrison, and now he’s flooding South Carolina with his liberal donors’ funds,” said SLF President Steven Law in a statement.

J.B. Poersch told CNN that the South Carolina race has been competitive for a long time.

“The problem with Lindsey Graham is nobody seems to trust him,” Poersch said. “That sentiment of not trusting Lindsey Graham knows no party.”

Targeting suburban women

Harrison has to hope for a series of fortunate events to beat Graham. He has to bring out Democratic voters, while appealing to Republicans who are turned off by the senator in the Trump era.

Amanda Loveday, a former executive director of the South Carolina Democratic Party, said Harrison “has run the most effective Democratic statewide race that we’ve seen in modern history.”

She said that white suburban voters, especially women “who are just tired of Trump,” could “determine how this election is won.”

Both campaigns are clearly targeting them. Harrison has aired one television ad featuring a woman named Robin from North Charleston, a former Graham supporter now attacking the senator for wanting to slash protections for those with pre-existing conditions like her. “He might as well cut this tube,” she says, holding onto what helps her breathe.

Another Harrison ad from another former Graham supporter, Melissa in Fort Mill, which is south of Charlotte, North Carolina, alleges that the senator “has changed” and that it is now time for a change.

Security Is Strength has responded with one of its own ads featuring a young mother and teacher, Anna Coleman, who says, “I want my family to be safe.” She then attacks Harrison for being “part of this liberal culture that is tearing our country apart.” It then seeks to tie the Democratic candidate with the left’s defund the police effort, which Harrison rejects, showing images of mobs on the streets. “I mean defund the police,” says Coleman. “That’s just crazy.”

Loveday, the South Carolina Democratic strategist, said that one important factor in the Senate race is Bill Bledsoe, a Constitution Party candidate, whom she said will still be on the ballot in November, even though he dropped out last week and endorsed Graham. The last Democratic candidate to win a statewide race, South Carolina Superintendent of Education Jim Rex, defeated a Republican in 2006 by 455 votes when four third-party candidates also ran for the office.

“That’s going to be huge for Jaime,” said Loveday. “[Bledsoe’s] name will appear on every ballot in the state of South Carolina. And if you vote for him, it could potentially determine the results of the election.”

Harrison grew up poor in Orangeburg, and was raised by his grandparents before attending Yale University and Georgetown Law. He worked as a staffer for South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn, led the state Democratic Party, and worked as a lobbyist with clients including Michelin, Boeing and the South Carolina Ports Authority. His message echoes Barack Obama’s slogans from 2008. “It’s not about left versus right,” says Harrison. “It’s about right versus wrong.”

Graham has attacked Harrison’s lobbying career, noting one of his clients was a hedge fund company that had previously sued Hurricane Katrina victims – a charge Harrison’s campaign has called misleading since it was before Harrison worked on behalf of the company.

But the senator’s overall message is that while Harrison is a liberal, Graham is going to ensure that Barrett will be confirmed this month.

Yet even as Trump is more popular in South Carolina then he is in other states where vulnerable Republican senators are running, polls have shown a dip in the President’s standing here. Whether that’s enough to end Graham’s 26-year career in Congress is an open question.

“I think we’re a team,” Graham told CNN when asked if his fortunes were tied to Trump’s. “Sometimes he says some things that are difficult to be honest with you. But Trump’s going to win this state because of his record. And I’m going to win because of my record. And this is a conservative state.”

CNN’s David Wright contributed to this report.