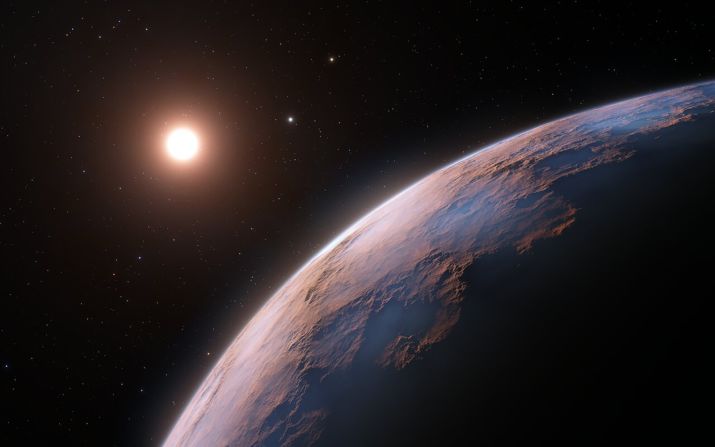

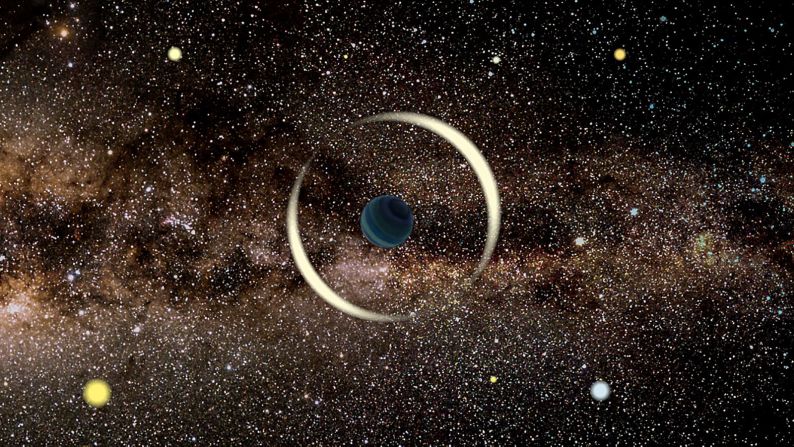

Taking a second glance in space can be rewarding, especially when a closer look revealsa weird exoplanet.

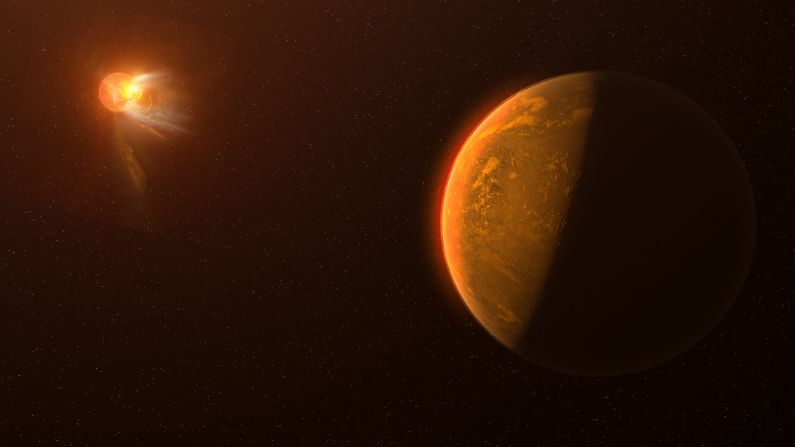

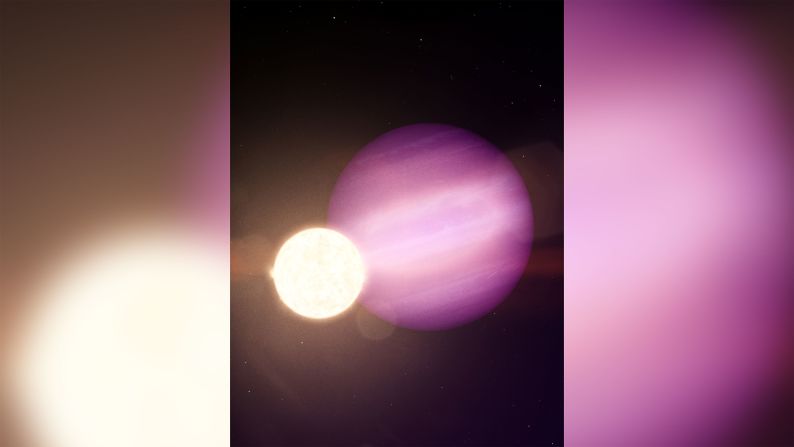

An ultra-hot exoplanet with searingtemperatures that can turn iron from a solid to a gashas been detected orbiting a star 322 light-years away in the Libra constellation. The observation was made by the European Space Agency’s Cheops mission, or Characterising Exoplanet Satellite.

This celestial body is the first finding of the mission, which launched in December 2019. Although the planet was first detected in 2018, Cheops has providedmore details about this strange world. Cheops has a unique mission in that it follows up on stars known to host exoplanets and characterizes any planets around them.

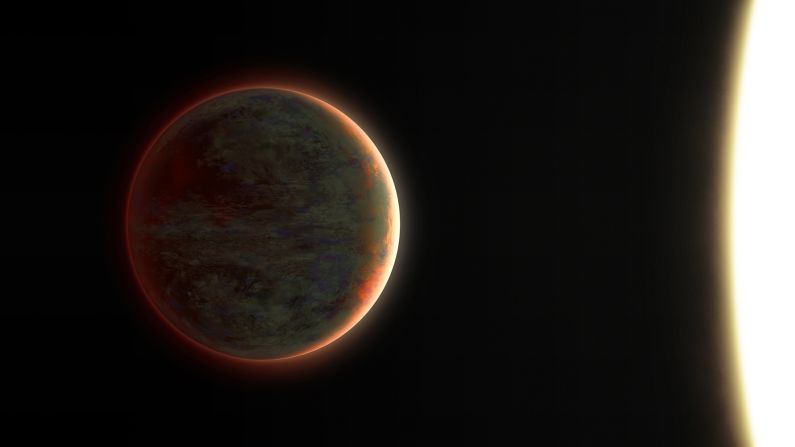

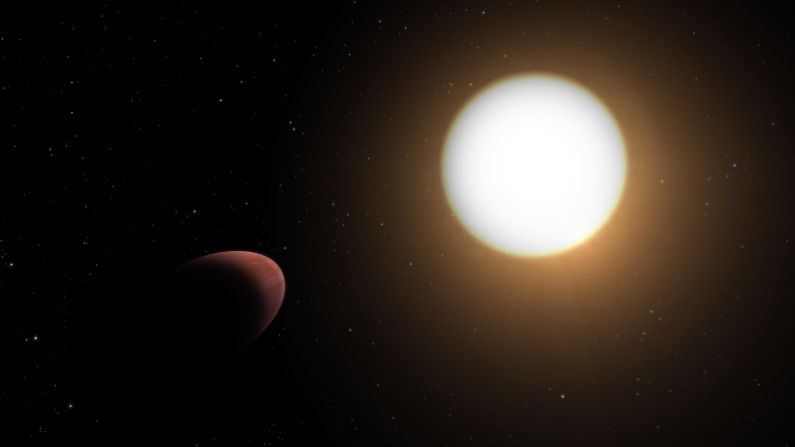

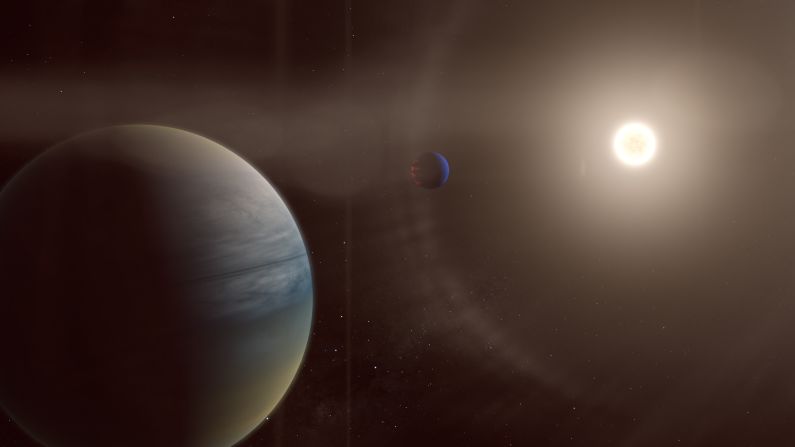

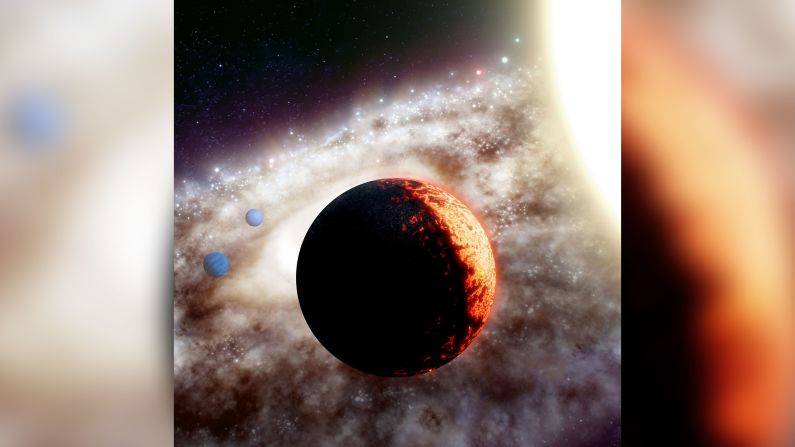

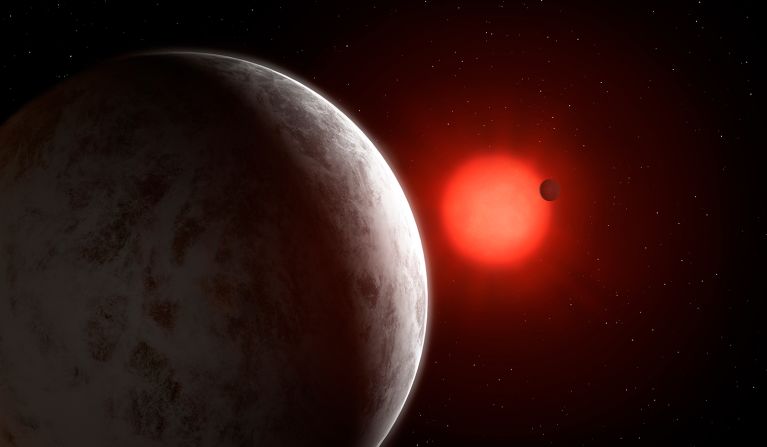

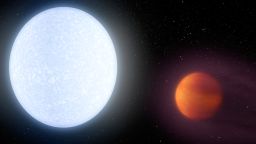

The planet, called WASP-189 b, is considered to be one of the hottest and most extreme exoplanets ever discovered. Exoplanets are planets outside of our solar system.

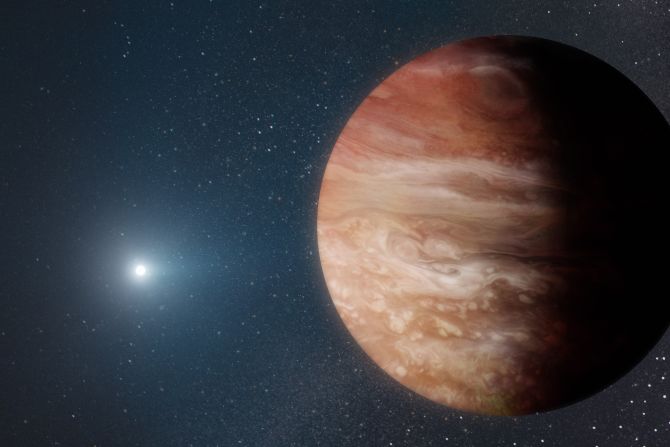

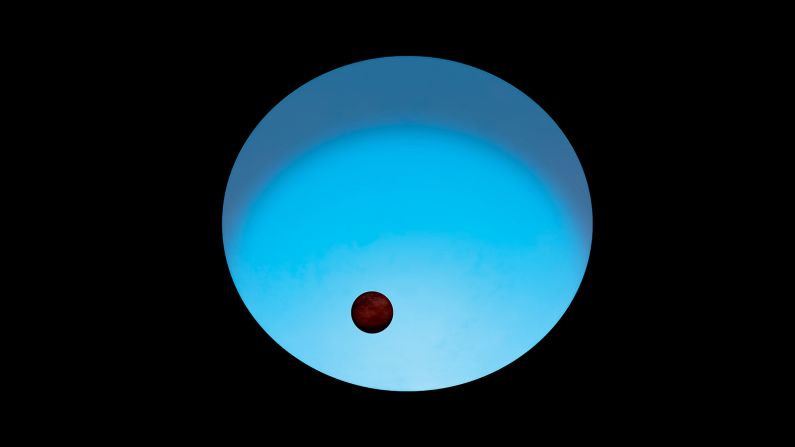

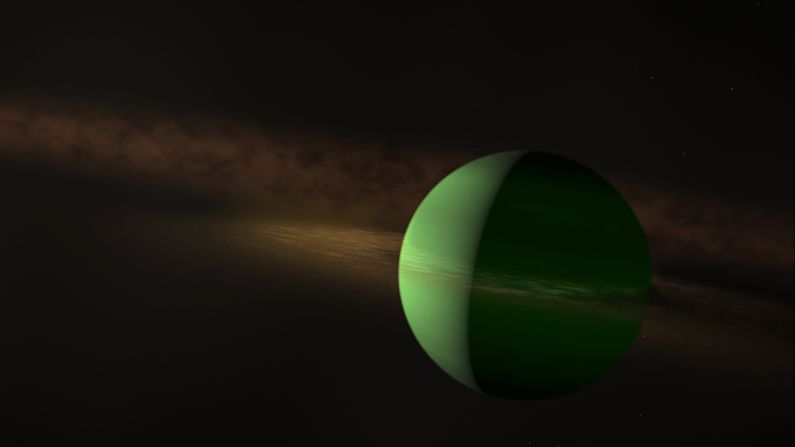

WASP-189 b is what scientists call an “ultra-hot Jupiter.” While the exoplanet is a gas giant, similar to Jupiter in our solar system, it’s much hotter because it orbits very close to its host star. This planet completes an orbit around its star every 2.7 Earth days. What’s more, the planet is20 times closer to its star than Earth is to the sun.

Meanwhile, the star is larger than our sun and more than 2,000 degrees hotter. This causes the star to look blue, rather than yellow or white.

“Only a handful of planets are known to exist around stars this hot, and this system is by far the brightest,” said Monika senior researcher at the University of Geneva and lead author of the new study, in a statement. “WASP-189 b is also the brightest hot Jupiter that we can observe as it passes in front of or behind its star, making the whole system really intriguing.”

The quest for light

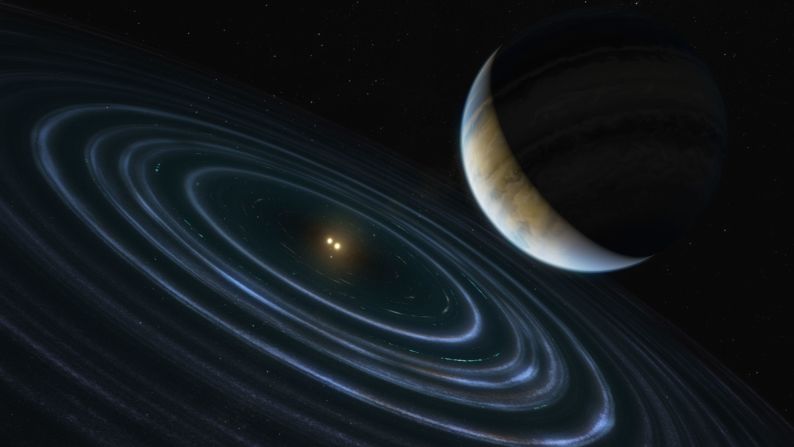

Cheops observes nearby stars to search for exoplanets around them. It can measure changes in light as planets orbit their stars with exceptional precision, which can help reveal details about the planets.

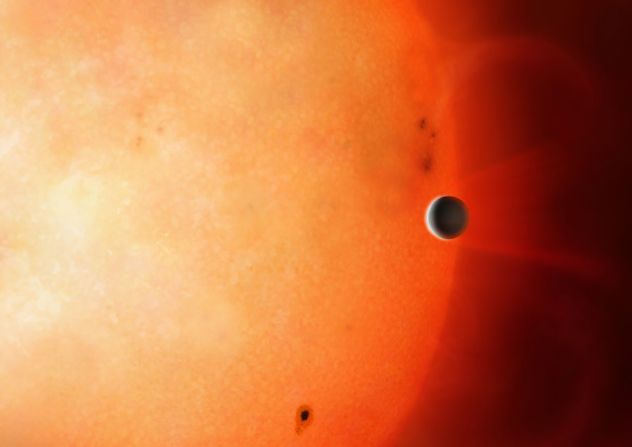

Researchers were able to capture an occultation and a transit of the planet and the star using Cheops. During an occultation, the planet passes behind the star. A transit occurs when the planet passes in front of the star.

These indirect methods of detecting the planet help the researchers learn more about it since they can’t actually observe the planet itself.

“As the planet is so bright, there is actually a noticeable dip in the light we see coming from the system as it briefly slips out of view,” Lendl said. “We used this to measure the planet’s brightness and constrain its temperature to a scorching 3200 degrees C (5792 degrees Fahrenheit).”

At this temperature, metals vaporize – so you wouldn’t want to live on WASP-189 b.

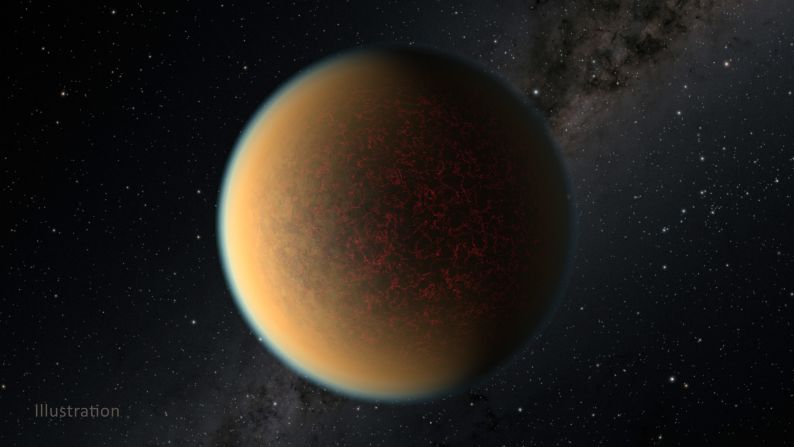

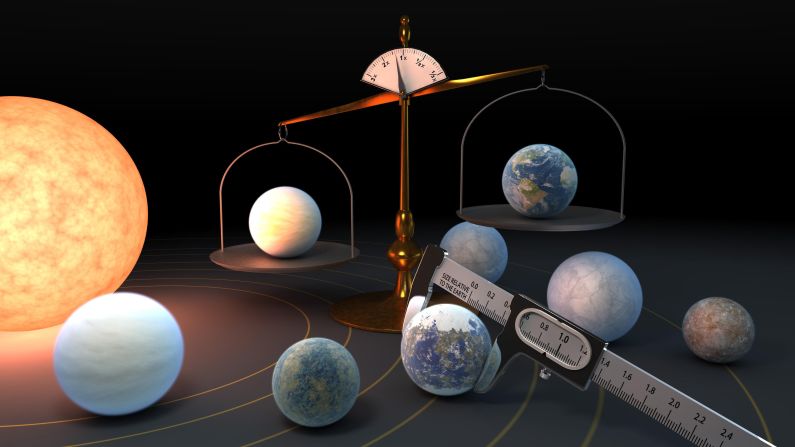

During the transit, the researchers were also able to determine that the planet was 1.6 times the radius of Jupiter.

Observations of this system revealed aspects of the star as well. The star, called HD 133112, is one of the hottest stars known to host a planet.

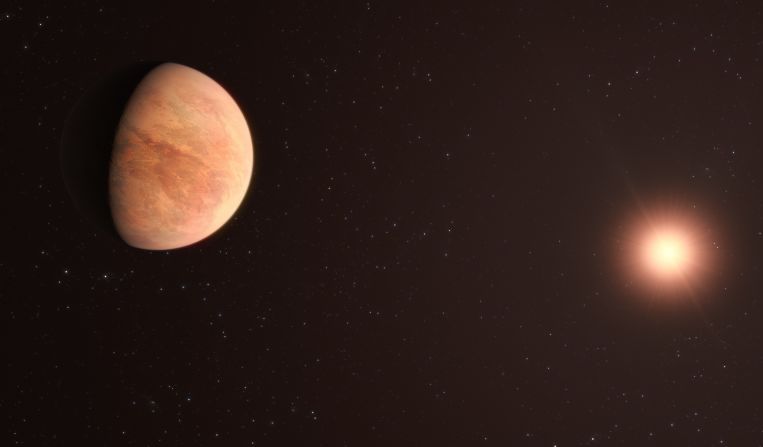

“We also saw that the star itself is interesting – it’s not perfectly round, but larger and cooler at its equator than at the poles, making the poles of the star appear brighter,” Lendl said. “It’s spinning around so fast that it’s being pulled outwards at its equator! Adding to this asymmetry is the fact that WASP-189 b’s orbit is inclined; it doesn’t travel around the equator, but passes close to the star’s poles.”

Planets typically have these tilted orbits when they form far away from the star and are later pushed closer to it. This migration can happen if multiple planets exist in the system and push each other around with their gravitational influence.Or it could be due to the forces of another star. So it’s likely that the planet experienced one of these scenarios.

This planet is tidally locked with its star, meaning one side always faces the star and the other side of the planet always faces away.

“They have a permanent day side, which is always exposed to the light of the star, and, accordingly, a permanent night side,” Lendl said. “This object is one of the most extreme planets we know so far.”

More exoplanets on the horizon

“This first result from Cheops is hugely exciting: it is early definitive evidence that the mission is living up to its promise in terms of precision and performance,” said Kate Isaak, Cheops project scientist at ESA, in a statement.

Cheops is the ESA’s first mission dedicated to characterizing known exoplanets. The mission is a collaboration between ESA and Switzerland, and the mission’s Science Operations Center is operated from the University of Geneva’s observatory.

“Cheops has a unique ‘follow-up’ role to play in studying such exoplanets,” Isaak said. “It will search for transits of planets that have been discovered from the ground, and, where possible, will more precisely measure the sizes of planets already known to transit their host stars. By tracking exoplanets on their orbits with Cheops, we can make a first-step characterisation of their atmospheres and determine the presence and properties of any clouds present.”

Over the next few years, Cheops will detect and characterize exoplanets and could identify targets for future missions that could study their atmospheres.

“Cheops will not only deepen our understanding of exoplanets, but also that of our own planet, Solar System, and the wider cosmic environment,” Isaak said.