During the coronavirus surge in Texas this summer, Dr. Thomas Patterson said he only had enough of the anti-viral drug remdesivir for about a third of his patients, and was forced to pick and choose who would get the only drug authorized in the United States to treat Covid-19.

Meanwhile, Dr. Ahmedul Kabir in Bangladesh has plenty.

“We have no shortage of remdesivir in our hospitals,” said Kabir, a professor of medicine at Dhaka Medical College. “Bangladesh is a third world country, and we have sufficient amounts. It’s really surprising that the US doesn’t. There should be plenty of remdesivir there.”

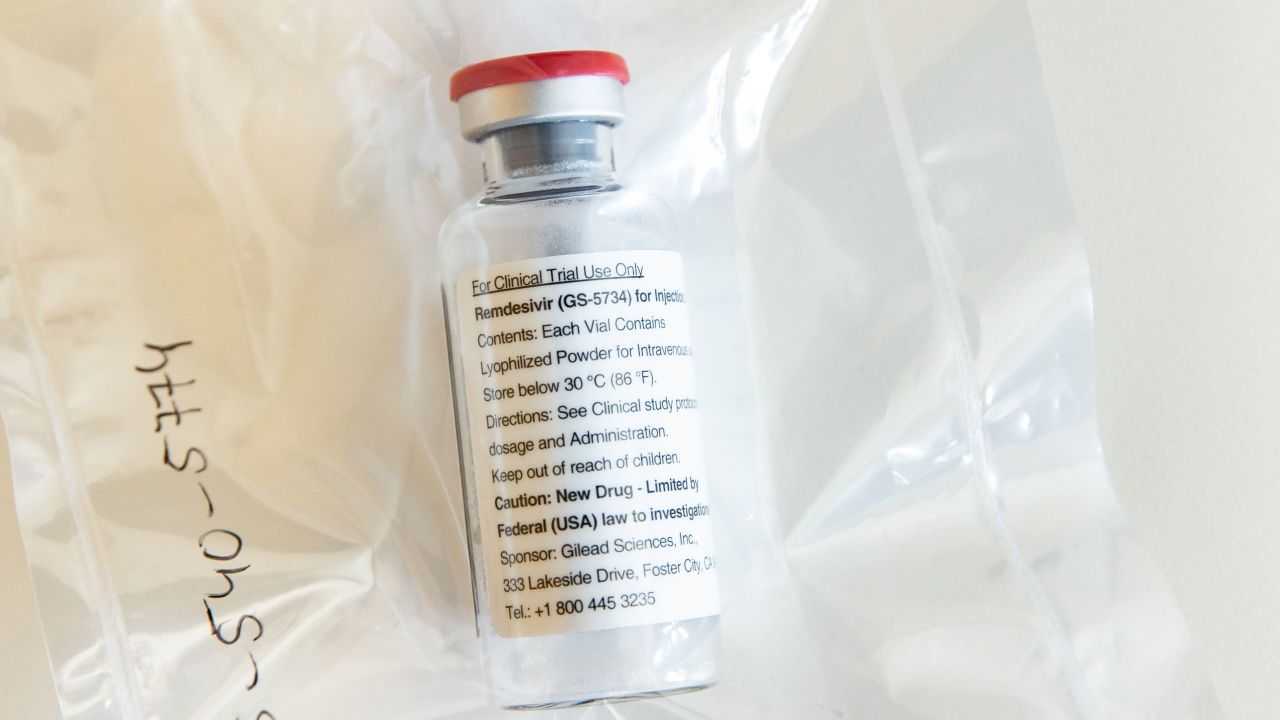

A CNN investigation into remdesivir finds that doctors in several developing countries report ample supplies of the drug, while US patients have faced shortages – even though the drug is made by a US pharmaceutical company and was developed with the help of US taxpayer money.

“The government funded it, and patients in hospitals like ours couldn’t get it,” said Patterson, chief of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

At a press conference Tuesday, physicians, advocates and a member of Congress excoriated the Trump administration for failing to secure a larger supply of remdesivir.

“Some whose suffering could be reduced and hospitalization shortened receive no relief because of Trump’s refusal to act,” Rep. Lloyd Doggett, a Texas Democrat, said in a statement. “We could quickly expand supply if Trump would belatedly exert some leadership.”

In an email to CNN, a spokesperson for the US Department of Health and Human Services defended the President’s remdesivir decisions.

“President Trump is putting American patients first and through his leadership secured more than 90 percent of Gilead’s commercial supply of this life-saving treatment,” the spokesperson wrote, referring to the California pharmaceutical company that makes remdesivir.

‘Very close to falling off the cliff’

Data presented by Gilead Sciences to the US Food and Drug Administration does not show that remdesivir saves lives. Rather, it shows that the drug shortens hospitals stays, on average, from 15 days to 11 days for patients with severe Covid-19. The FDA gave Gilead emergency use authorization for remdesivir in May based on that data.

The drug costs $2,340 for a five-day course of treatment, and US hospitals don’t purchase it directly the way they do other drugs. Because there isn’t enough to go around, HHS arranges for remdesivir to be shipped regularly to hospitals.

Gilead says it has enough for the demand, but doctors interviewed by CNN say they don’t always have a sufficient supply for all their patients.

Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at UCSF Health, said that several times he’s come close to not having enough for his Covid-19 patients.

“We’ve been very close to falling off the cliff,” he said.

Then Chin-Hong got the idea of asking nearby hospitals to borrow some of their remdesivir, promising he’d return the favor when his hospital’s next shipment came in.

“It’s like we’re in a medieval market and doing trades with chickens and goats,” he said.

A July survey of 131 hospitals by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists showed that nearly one-third reported that they hadn’t received enough remdesivir to treat all of their Covid-19 patients who met the guidelines for the drug.

Paths to increase remdesivir supply in the US

Kabir, the physician in Bangladesh, said his hospital has had plenty of remdesivir because they’re purchasing generic versions of the drug.

Doctors from other developing countries said their hospitals are also using generics.

“We have enough remdesivir in our country,” said Dr. Bilal Aziz, an assistant professor of medicine at King Edward Medical University in Lahore, Pakistan.

“We don’t have any shortages,” said Dr. Endymion Tan, an infectious disease specialist at Metropolitan Medical Center in Manila in the Philippines.

Several companies make generic remdesivir, including Beximco Pharmaceuticals in Bangladesh.

“We can make more. We’re currently producing around 80,000 vials per month, and we have capacity and capability to produce up to 150,000 per month,” said Rabbur Reza, Beximco’s chief operating officer.

But only Gilead is allowed to sell remdesivir in the US. There are no generics, and Gilead has no competition.

Christopher Morten, a patent law expert at NYU School of Law, said the Trump administration could change that if they wanted to.

Morten said the administration could exercise a law that allows the government to “open up” patents so that Gilead could still profit from the drug, but other companies would be allowed to make generic versions of it.

“The US government always has the power to – to put it colloquially – break patents when those patents stand in the way of competition, and Gilead is guaranteed fair compensation under the same law, so Gilead would still make a lot of money,” said Morten, deputy director of NYU Law’s Technology Law and Policy Clinic.

He said in the case of remdesivir, he believes the government has a second option as well.

The US can legitimately claim to be the co-owner of the patents for remdesivir, since government funding and expertise went into making it, according to a paper coauthored by Morten and James Krellenstein, co-founder of the COVID Working Group NYC.

“I believe that the US government co-invented and co-owns the most important patents on remdesivir,” Morten said.

Gilead disagrees, and so does HHS.

“There are many patents for remdesivir, and the U.S. Government has participated in the research for some of these patents. The U.S. Government is not listed as a co-inventor on any of the current remdesivir patents,” according to the statement from the HHS spokesperson.

Now the US Government Accountability Office is investigating that very issue.

A GAO investigation

In July, two Democratic lawmakers, Sen. Debbie Stabenow from Michigan and Carolyn Maloney from New York, asked the Government Accountability Office to investigate the discovery and development of remdesivir.

“Remdesivir was developed with an estimated $70 million in federal funding, and Gilead relied on key scientific contributions from government scientists,” the congresswomen wrote.

The GAO expects to have a report by the end of the year, according to Candice Wright, acting director of the GAO’s Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics division.

She said her team is speaking with officials at HHS and the Department of Defense, which worked with Gilead on remdesivir.

“We know there were federal contributions based on peer reviewed articles,” Wright said.

On its website, Gilead details the work the company has done on remdesivir since 2014 with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, and the National Institutes of Health.

In an email to CNN, Gilead spokesman Chris Ridley emphasized the role Gilead – not the government – played in the drug’s development.

“The research that led to remdesivir began over a decade ago. Gilead researchers invented remdesivir, identified its broad-spectrum antiviral activity, optimized the formulation of the product, and scaled up the manufacturing process. Although government funding was used to further characterize remdesivir’s profile after its initial discovery, this did not result in the creation of the underlying intellectual property invented by Gilead,” Ridley wrote.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Ridley also said government grants totaling about $76 million were made to academicians who collaborated with Gilead, “a portion of which was used to support their work with Gilead on remdesivir.”

“Gilead has made significantly greater investments in the research and development of remdesivir than public sources,” he added.

But Morten, the NYU lawyer, said it’s clear to him that Americans are paying twice for remdesivir – once to help develop it and a second time to purchase it for treatment of Covid-19.

“I think this is troubling – it’s a real sweetheart deal for Gilead,” he said.

CNN’s John Bonifield contributed to this story.