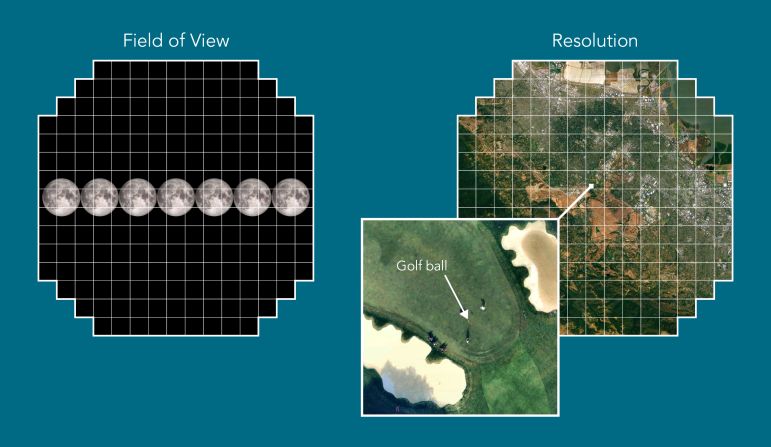

The world’s largest digital camera can spot a golf ball from 15 miles away.

When the Vera C. Rubin Observatory begins observations in 2023, its SUV-size camera will be able to capture complete panoramas of the southern sky every few nights. And that requires a new type of camera never seen before.

The imaging sensors for the world’s largest digital camera have captured the first-ever 3,200-megapixel images by teams at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (originally named the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center) in California

Once this array of sensors is installed in the camera at SLAC and delivered to the Rubin Observatory in Chile, it will contribute to the observatory’s 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

This survey will serve as a catalog of billions of galaxies and astrophysical objects, essentially creating “the largest astronomical movie of all time” and unlock the mysteries of the universe.

The first 3,200-megapixel images captured using the sensors are so sprawling that they would require 378 4K ultra-high-definition TV screens to showcase just one of them at its full size.

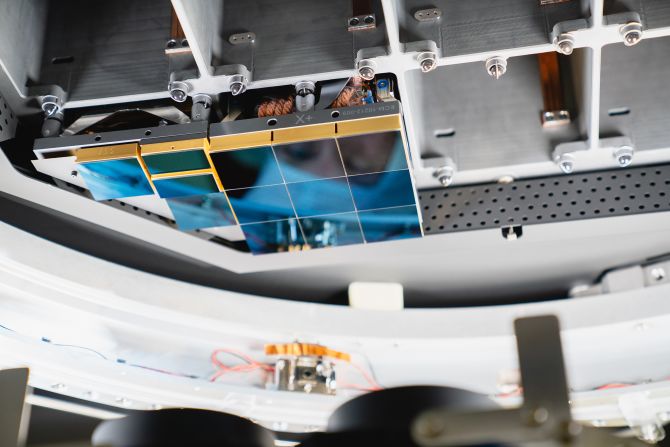

The assembly of the sensors in the camera’s focal plane was completed in January, and the first images were used to test it.

“The focal plane will produce the images for the LSST, so it’s the capable and sensitive eye of the Rubin Observatory,” said Vincent Riot, LSST camera project manager, in a statement. Riot is from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

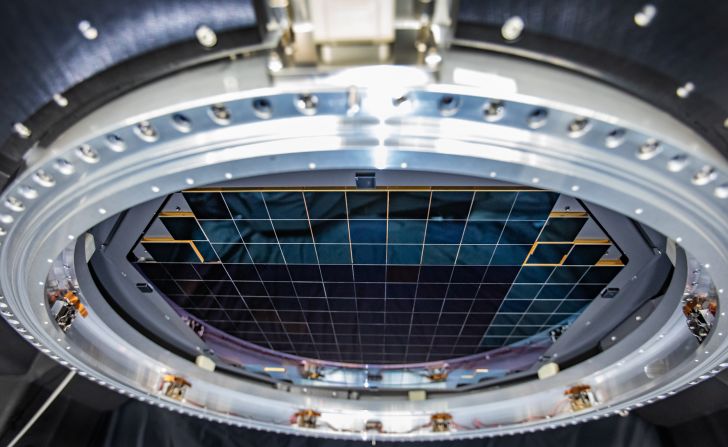

The camera’s focal plane, similar to an imaging sensor in a digital camera, includes 189 sensors that provide 16 megapixels each. And it’s more than 2 feet wide, compared to the normal 1.4-inch-wide sensor in digital full-frame cameras.

This makes the sensor large enough to image a part of the sky that is equal to 40 full moons.

The observatory’s capabilities will enable it to spot faint objects 100 million times dimmer than what we can see with the naked eye. It’s designed to map the Milky Way, explore dark energy and dark matter, and survey the solar system.

During the 10-year survey, the camera is expected to image 20 billion galaxies.

“These data will improve our knowledge of how galaxies have evolved over time and will let us test our models of dark matter and dark energy more deeply and precisely than ever,” said Steven Ritz, project scientist for the LSST Camera at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in a statement.

“The observatory will be a wonderful facility for a broad range of science – from detailed studies of our solar system to studies of faraway objects toward the edge of the visible universe.”

Capturing the first images

Before the LSST camera could point its eye to the sky, it had to undergo delicate assembly as well as testing.

The focal plane took six months to assemble. Each grid of nine sensors is called a scientific raft, and 25 rafts had to be fitted into their spots along the grid. The sensors can easily crack if they come in contact with each other, and they only have a tiny gap between rafts – less than five human hairs wide.

And the rafts cost about $3 million each. This explains why the team spent a year preparing before starting to install any of the rafts.

The focal plane itself is inside a cryostat, a device that keeps the sensors at a cool negative 150 degrees Fahrenheit, which is the temperature they require to operate.

Although assembly of the focal plane was completed in January, the coronavirus pandemic kept the team from accessing the lab to take the first images using the focal plane in May – and even then, with limited staff and social distancing in place.

While testing of the focal plane continues, the first images are a huge milestone.

Although the camera itself isn’t completely assembled, the team was able to use a 150-micron pinhole that acted as a projector for the focal plane to take some initial pictures.

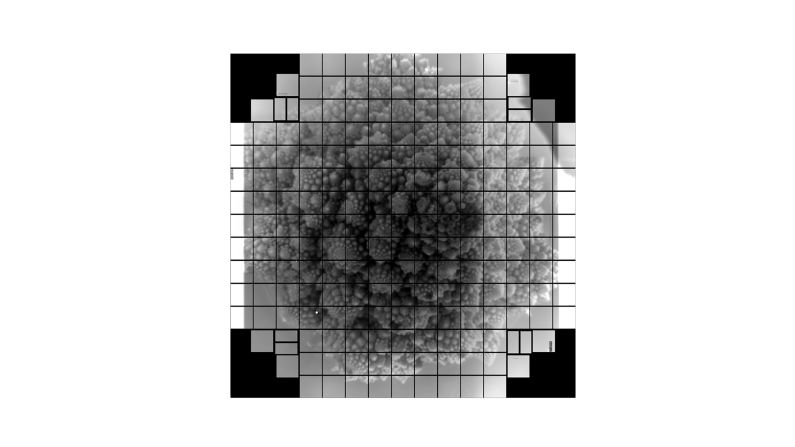

The first images include a Romanesco vegetable, which was chosen for its detailed surface, as well as Vera Rubin herself, who the observatory is named for.

Rubin, who died in 2016, once mentored fellow aspiring female astronomers and advocated for women in science. It’s fitting that the first national US observatory named for a female astronomer is in her honor. Rubin, considered to be one of the most influential female astronomers, provided some of the first evidence that dark matter – which comprises much of the universe but can’t be seen – existed.

The new images revealed the amount of detail the sensors can capture.

“Taking these images is a major accomplishment,” said Aaron Roodman, professor and chair of the particle physics and astrophysics department and the scientist at SLAC responsible for the assembly and testing of the LSST camera, in a statement.

“With the tight specifications we really pushed the limits of what’s possible to take advantage of every square millimeter of the focal plane and maximize the science we can do with it.”

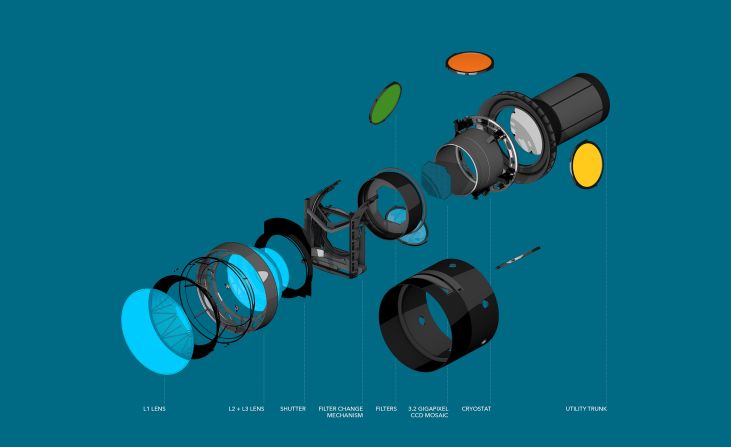

Next comes the assembly of the camera: inserting the focal plane and cryostat into the camera body, adding the world’s largest optical lens, shutter and filter exchange system.

The team estimated that the camera would be ready for testing by mid-2021 before it’s sent off to Chile.

“It’s a milestone that brings us a big step closer to exploring fundamental questions about the universe in ways we haven’t been able to before,” said said JoAnne Hewett, SLAC’s chief research officer and associate lab director for fundamental physics, in a statement.