Blood thinners appear to reduce the risk of death by up to 50% among seriously ill, hospitalized coronavirus patients, researchers reported Wednesday.

And patients given anticoagulants also were 30% less likely to need a ventilator to help them breathe, a team at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York reported.

Their study of more than 4,300 patients also those who died often had evidence of blood clots throughout their bodies, even though many of them had no symptoms of the problem. It’s more evidence of the serious, systemwide blood clotting that coronavirus infections can cause, but the findings offer hope of countering the effect.

“Compared to no anticoagulation, both prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with decreased mortality and intubation,” the team wrote in their report, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It was not a randomized controlled study, the gold standard for medical research. The study’s leader, Dr. Valentin Fuster, says that’s next. “An international randomized trial just started with 15 institutions,” Fuster told CNN. “We are comparing three types of anticoagulants that work.”

Fuster’s team said 60% of patients who were not given anticoagulants were discharged alive, 26% of them died in the hospital and 13% were still in the hospital.

When patients got the drug prophylactically to prevent blood clots, 75% were released alive, 22% died in the hospital and 3% were still hospitalized during the study period. The researchers said the reduction in the risk of death was similar in patients who got anticoagulants either to prevent clots, or after they began showing evidence of clotting.

Sal Mazzara is one of the survivors. He was hospitalized in early April as his coronavirus infection worsened and stayed on a ventilator for a month.

“Sal did not have any blood clots but he was given medicine every day for blood clots to prevent them,” his wife, Josephine Mazzara, told CNN. At first Mazarra got the clotbusting drug tPA, used for emergency treatment of a stroke. He later got heparin and was sent home with Eliquis, known generically as apixaban – a pill approved for preventing stroke.

Mazzara’s treatment required heavy sedation and an incision in his throat so he could be intubated. “It was a horrible, horrible experience,” Josephine Mazzara said.

“There’s not much I can remember,” Sal Mazzara, 48, told CNN. “I completely blacked out.”

The only specific treatment for coronavirus is the antiviral drug remdesivir. Mazzara got that drug, too, during his treatment, Josephine Mazzara said.

Doctors have also learned that steroids, specifically dexamethasone, can also help patients recover better from coronavirus infections. Trials are under way to test blood-based therapies that deliver various types of antibodies to help patients fight off the infection, using plasma donated by people who have recovered from infections.

In the absence of a slam-dunk treatment for the virus, many medical teams are taking a cocktail approach, giving their patients a combination of drugs to control the immune response, control the virus and to control blood clotting.

Mazzara continued on the blood thinner for a month after his release from the hospital in May. “I’m like 90% back,” he said.

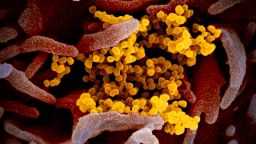

Soon after the pandemic hit New York City hard in March, doctors started noticing their patients were suffering from systemwide blood clotting. Blood clots clogged up kidney dialysis equipment and damaged the lungs, livers and hearts of patients.

Physicians now believe the inflammation caused by coronavirus infection is causing the clotting. Sometimes it causes no symptoms until it is too late.

In the Mt. Sinai study, autopsies on some of the patients who died showed that 42% had blood clots, including in their brains, lungs, liver and heart. “They never had the clinical syndrome of a thrombotic disorder. It was silently causing damage,” Fuster said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

The doctors used several different anticoagulants and often more than one on each patient, so it is not possible to say which ones worked best. But Fuster said low molecular weight heparin and apixaban both showed positive effects.

The Mount Sinai team published study results involving 2,000 patients in May. Wednesday’s report follows up with more patients who were treated more consistently.