In an era of hypervigilance during a pandemic, whether some of our friendships will survive is up in the air.

Our brains have established methods for recognizing people as close friends or acquaintances, and “the closest ties are built on a substantial investment of time and trust — both of which may be challenged by the current pandemic,” said Andrea Courtney, a postdoctoral research fellow in psychology at Stanford University in California, who wasn’t involved in a newly released review on social bonds.

How humans develop and maintain relationships with friends and family is similar to the behaviors of societies in our evolutionary history and those of other primates, according to the review published Tuesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

Although many of us live in cities along with millions of other people, our personal social worlds contain anywhere from 78 to 250 people, with an average of about 154 individuals. That means that most people interact with a small number of other people — and those people remain relatively stable over time, according to review author Robin Dunbar, a professor emeritus of evolutionary psychology in the department of experimental psychology at the University of Oxford in England.

These people are organized into layers within social networks, and those layers are dependent on cognitive, emotional and time constraints on our capacities for interaction.

The organization of our cognitive social networks

Why can most humans handle only about 154 people? That value as a natural group size relates to the size of the brain’s neocortex, which is involved in sensory perception, motor commands, spatial reasoning, language and conscious thought. Having robust personal social networks is positively correlated with brain size and capacity for mental functions that help to assess other people.

These networks consist of layers in accordance with relationships of varying quality: People considered to be intimates (family) and close friends are close in proximity and small in number. Types of friends and acquaintances extend further away from someone and grow in numbers.

How both humans and animals bond

The bonding process in both primates and humans is complex and time-consuming, the review said.

When animals are faced with the issue of maintaining group stability amid stresses, the solution is bonded relationships, which help ensure that members will behave similarly to one another and stay together. Primates accomplish this bonding by social grooming — an activity that is time-consuming, but can also create a sense of reciprocity, obligation and trust.

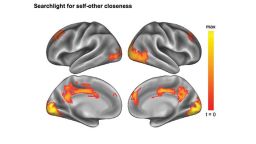

Whether we humans trust someone is partly determined by the time we can spend with that person. Human social networks reflect how we invest our time in certain people, which also determines the quality of those relationships. The human bonding process involves two factors that work together: how the human version of social grooming activates endorphins and how our social brain uses interpersonal closeness.

When our brains activate and use up endorphins stimulated by human touch, we can experience an opioid-like sense of relaxation, contentment and warmth that seems to provide bondedness, the review said. That bondedness leads to a mental sense of trust and obligation to help one another, but the intimacy and demand on time limit the number of relationships one can bond with using touch.

Endorphins are fleeting, so their need for constant activation to maintain bonding levels make bonding time-consuming.

Laughing, singing, dancing, storytelling, eating and drinking are activities that, when done with others, can trigger the endorphin system in a way that is time efficient and “grooming-at-a-distance,” the review said.

Virtual activities “slow down the rate of decay on relationships, but they won’t stop them (from) dying eventually,” Dunbar said in an email.

“Face-to-face is necessary for that, it seems. There is something very special about being able to see the whites of their eyes across the table, to reach out and touch them, that no digital media can yet match.”

Seven pillars of friendship

Our knowledge of other people, which is built up by being in close contact, helps us bond and increase trust that others will meet our needs.

Sharing common cultural dimensions known as the “Seven Pillars of Friendship” — language or dialect, place of origin, educational path, hobbies and interests, worldview, musical tastes and sense of humor — can influence the strength and altruism of relationships, according to a prior analysis by Dunbar.

The pillars identify “what community you belong to” and the community “whose mores and behavior you understand in a very intuitive way,” Dunbar said in the review. These commonalities enable relationships to flow since both parties would better understand each other, share similar interests and have a sense of how much they can trust one another.

Emotional and physical closeness

At the core of human and primate friendships are being close in terms of spatial proximity and feeling close by emotional proximity, influenced by the time spent together.

“These ensure that bonded individuals stay together so that they are on hand when support is needed,” Dunbar said in the review.

To hold someone in your close friends layer, you need to see them at least once a week; the best friends layer at least once a month; the friends layer at least once a year, Dunbar said.

“Drop below those rates, and the person will slip into the layer below within a few months,” he added. “This is because the time you invest in direct interaction with someone determines the sense of emotional closeness you have with them – and the sense that this is mutual.”

The social and health consequences of personal ties

Trust and time available are crucial to social networks. When those are threatened by internal stressors or external threats (like a pandemic), relationships are at risk for declines in emotional strength, major upheavals or ultimately breaking down.

Because of the greater likelihood of forgiveness and inherent bond, family members have appeared to bounce back from the lack of opportunities to interact, Dunbar said. Friendships require more investment for constant connection and are more likely to fade when under threat.

Social breakdowns could have ill effects for our health, well-being and longevity, the review said. The number and quality of close friendships a person has can affect his or her happiness and capacity to recover from illness. Smaller social networks are associated with greater feelings of isolation and loneliness, which can affect rates of disease and death.

In light of the social distancing, quarantining and lockdowns imposed by Covid-19, Dunbar anticipated a few likely effects: a weakening of friendships that could make for awkward reunions; an increased effort to contact old friends after lockdowns; and fear of contracting the virus to reduce how often some people (introverts and the psychologically more cautious) visit places where they would encounter people they don’t know.

The inability to assess the behaviors and infection risk of low-rank friends and distant family members could result in smaller, more inverted social networks, Dunbar predicted. Network patterns may return to normal within a year, but some friendship ties might be weakened enough to become acquaintances, the review said.

“Focusing more time on close relationships may boost well-being in the short term,” Courtney said in an email. “In fact, recent research has observed a decrease in loneliness following the pandemic — this may reflect the fact that many people are now clinging to their closest ties. … Although physical contact is now much more limited, many of these other (virtual) bonding opportunities are just as abundant as ever.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

To keep up relationships, emotional closeness and trust during this time, stay in virtual touch as much as possible, Dunbar suggested.

And remind your loved ones, “I’m still here and thinking of you.”