A marine reptile called an ichthyosaur ripped into the nutritious torso of a slightly smaller marine reptile 240 million years ago, swallowed it and promptly died, according to a new study.

The animal and its stomach contents fossilized and preserved the remains of the other animal, called a thalattosaur.

This discovery provides the best evidence yet of megapredation, which is when large animals prey on other animals that are the size of humans or larger.

“We have never found articulated remains of a large reptile in the stomach of gigantic predators from the age of dinosaurs, such as marine reptiles and dinosaurs,” said Ryosuke Motani, study coauthor and professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Davis.

“We always guessed from tooth shape and jaw design that these predators must have fed on large prey but now we have direct evidence that they did.”

The study published Thursday in the journal iScience.

Ichthyosaurs were almost dolphin-like marine reptiles that first appeared in Earth’s oceans about 250 million years ago. They had bodies similar in structure to fish, like tuna, but needed to breathe air in the way that modern dolphins and whales do.

They were likely the apex predators – the predators at the top of their environment’s food chain – like orca and great white sharks are in the oceans today. But actual evidence to determine who the apex predators were in prehistoric times is challenging.

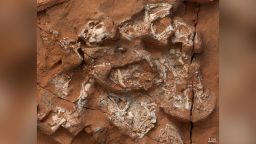

That’s why it was significant when anearly complete fossil of an ichthyosaur, called Guizhouichthyosaurus, was found in a quarry located in China’s Guizhou province in 2010. Within the stomach of the fossil was a curious bulge of other bones.

An analysis revealed this cluster of fossils belonged to another marine reptile, the thalattosaur Xinpusaurus xingyiensis. Thalattosaurs were much more like lizards and used their four limbs to help them paddle through the water.

The ichthyosaur measured about 15 feet long, and the thalattosaur, while skinnier, was still 12 feet long.

When the ichythyosaur consumed the thalattosaur, it swallowed its torso, including front and back limbs, whole. Nearby,researchers found the fossil of the thalattosaur’s tail.

Determining a megapredator

The thalattosaur represents one of the longest fossils ever located inside the stomach of a fossilized marine reptile. So what happened that led to it becoming the meal of a marine reptile that was only slightly larger?

At first glance, the ichthyosaur didn’t look like a major predator. It had small teeth that resembled pegs, better adapted to helping it grasp animals similar to squid. Usually, sharp teeth with cutting edges are a requirement to slice into other large prey.

In this scenario, the ichthyosaur likely used its teeth to grab the thalattosaur, potentially breaking its spine, and then ripping it apart in the way that modern orca, crocodiles and leopard seals do.

There is also the possibility that the ichthyosaur scavenged an already-dead thalattosaur, but the researchers don’t believe that’s the case here.

Based on studies of decaying creatures in marine environments, the thalattosaur’s limbs would have detached first. Instead, they were still attached to the torso within the ichthyosaur’s stomach. Meanwhile, the tail, which would detach later if it was already dead, was found disconnected from the body yards away from the “crime scene.” This suggests the tail was ripped off by the ichthyosaur.

“Our finding suggests that megapredation was probably more common among ichthyosaurs than we previously thought,” Motani said.

Previously, other evidence, such as its size and the fact that three species of ichthyosaurs had sharp, cutting teeth, suggested they may be apex predators.

What killed this ichthyosaur?

“Our ichthyosaur’s stomach contents weren’t etched by stomach acid, so it must have died quite soon after ingesting this food item,” Motani said.

The researchers can only use the facts they have to piece together why the ichthyosaur died so quickly after eating the thalattosaur.

The thalattosaur, which was missing its head and tail, showed no signs of being digested by the ichthyosaur.

Meanwhile, the ichthyosaur’s neck is broken, even though its head and body remained intact.

They estimated that the thalattosaur was unusually large for its species.

The ichthyosaur’s broken neck indicates its cause of death since it wouldn’t have been able to breathe and there could be multiple causes of the break.

The ichthyosaur may have run into trouble trying to separate the thalattosaur’s head or tail, swallowing its massive trunk or the thalattosaur may have fought back by twisting and jerking, Motani said.

It likely didn’t help that the ichthyosaur’s neck vertebrae were more narrow in comparison with the rest of its body. But the true cause of death is only based on speculation.

Given that the team is still excavating the site of the fossil, which has been moved about a mile from the quarry to the Geopark Museum, the researchers are still uncovering new things. They want to determine how environments were changing at the time this marine life existed and what enabled them to move into the open seas.

“There are so many things to do,” Motani said. “We have more specimens from the quarry waiting for us to study them.”

“The quarry provides the earliest records of open-sea marine reptiles – marine reptiles first colonized the coastal waters about 10 million years earlier and were finally ready to expand into open seas by this time.”