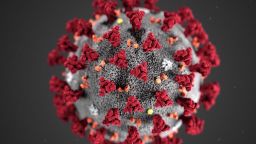

Since the coronavirus pandemic first began, evidence has emerged showing that Covid-19 can damage more than the lungs.

The disease caused by the novel coronavirus can harm other organs in the body – including the heart – and now two separate studies, published in the journal JAMA Cardiology on Monday, provide more insight into how Covid-19 may have a prolonged impact on heart health in those who have recovered from illness and may have caused cardiac infection in those who died.

“We’ve understood for a few months now that Covid-19 is not only a respiratory infection but a multi-system infection,” said cardiologist Dr. Nieca Goldberg, medical director of the NYU Women’s Heart Program and senior adviser for women’s health strategy at NYU Langone Health in New York, who was not involved in either study.

“There is an acute inflammatory response, increased blood clotting and cardiac involvement. And the cardiac involvement can either be due to direct involvement of the heart muscle by the infection and its inflammatory response. It could be due to blood clots that are formed, causing an obstruction of arteries,” Goldberg said.

“Sometimes people have very fast heart rates that can, over time, weaken the heart muscle, reduce the heart muscle function. So there are multiple ways during this infection that it can involve the heart.”

Inflammation of the heart

One of the JAMA Cardiology studies found that, among 100 adults who recently recovered from Covid, 78% showed some type of cardiac involvement in MRI scans and 60% had ongoing inflammation in the heart.

The study included patients ages 45 to 53 who were from the University Hospital Frankfurt Covid-19 Registry in Germany. They were recruited for the study between April and June. Most of the patients – 67– recovered at home, with the severity of their illness ranging from some being asymptomatic to having moderate symptoms.

The researchers used cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, blood tests and biopsy of heart tissue. Those data were compared with a group of 50 healthy volunteers and 57 volunteers with some underlying health conditions or risk factors.

The MRI data revealed that people infected with coronavirus had some sort of heart involvement regardless of any preexisting conditions, the severity or course of their infection, the time from their original diagnosis or the presence of any specific heart-related symptoms.

The most common heart-related abnormality in the Covid-19 patients was myocardial inflammation or abnormal inflammation of the heart muscle, which can weaken it.

This type of inflammation, also called myocarditis, is usually caused by a viral infection, Goldberg said, adding that she was not surprised by these study results.

“What they’re saying in this study is that you can identify myocardial involvement or heart involvement by magnetic resonance imaging,” Goldberg said.

The study has some limitations. More research is needed to determine whether similar findings would emerge among a larger group of patients, those younger than 18 and those currently battling coronavirus infection instead of just recovering from it.

“These findings indicate the need for ongoing investigation of the long-term cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19,” the researchers wrote.

‘This infection does not follow one path’

In the other JAMA Cardiology study, an analysis of autopsies found that coronavirus could be identified in the heart tissue of Covid-19 patients who died.

The study included data from 39 autopsy cases from Germany between April 8 and April 18. The patients, ages 78 to 89, had tested positive for Covid-19 and the researchers analyzed heart tissue from their autopsies.

The researchers found that 16 of the patients had virus in their heart tissue, but did not show signs of unusual sudden inflammation in the heart or myocarditis. It’s not clear what this means, the researchers said.

The sample of autopsy cases was small and the “elderly age of the patients might have influenced the results,” the researchers wrote. More research is needed whether similar findings would emerge among a younger group of patients.

“I think both of these studies are important,” Goldberg said.

“One pretty much shows that the MRI scan can help diagnose the myocardial injury that occurs due to Covid and it was confirmed on biopsy,” she said. “The autopsy study showed us something else that’s interesting – that you can have viral presence but not the acute inflammatory process. So this infection does not follow one path.”

‘An increasingly complex puzzle’

Both studies “add to an increasingly complex puzzle” when it comes to the novel coronavirus named SARS-CoV-2, Dr. Dave Montgomery, founding cardiologist at the PREvent Clinic in Sandy Springs, Georgia, said in an email on Tuesday.

“Taken together the studies support that SARS-CoV-2 does not have to cause clinical myocarditis in order to find the virus in large numbers and the inflammatory response in myocardial tissue. In other words, one can have no or mild symptoms of heart involvement in order to actually cause damage,” said Montgomery, who was not involved in the studies.

“Viruses in general have a way of making their way to organs that are quite remote from the original site of infection. SARS-CoV-2 is no different in this regard,” he said. “What is different is that this virus seems to preferentially affect cardiac cells and the surrounding cells. These studies suggest that the heart can be infected with no clear signs. Personally, in my practice, we have seen similar signs of inflammation, including pericardial effusions,” or fluid around the sac of the heart.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Dr. Clyde Yancy of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Dr. Gregg Fonarow of the University of California, Los Angeles, co-authored an editorial that accompanied the two new studies in the journal JAMA Cardiology on Monday.

“We see the plot thickening and we are inclined to raise a new and very evident concern that cardiomyopathy and heart failure related to COVID-19 may potentially evolve as the natural history of this infection becomes clearer,” Yancy and Fonarow wrote in the editorial.

“We wish not to generate additional anxiety but rather to incite other investigators to carefully examine existing and prospectively collect new data in other populations to con- firm or refute these findings,” they wrote.