The George Floyd protests have forced many White Americans to consider tough questions about race. But the most difficult question may be the one they’re asking themselves.

Google says searches for the term, “Am I racist,” have spiked in recent weeks to an all-time high. Floyd’s death at the hands of a White police officer has sparked a racial awakening in the US. Support for the Black Lives Matter movement has surged, and White people are snapping up books like “How to Be an Antiracist” and “White Fragility.”

But a Google search and a few books can only go so far in answering such a complex and loaded query.

So CNN called some activists, psychologists and historians and asked them: How would you help White people answer that question?

First, let’s define racism

The first step in self-knowledge is defining what it means to be a racist, and defining racism itself.

Wornie Reed, a veteran civil rights activist and the director of the Race and Social Policy Center at Virginia Tech, says, “A racist person is a person who commits racist acts.”

Those acts, he says, are backed by a set of beliefs that support the idea that race determines human traits and capacities and makes one race automatically superior to another.

“If they do racist things, I’m willing to call them a racist,” Reed says. “You can be a racist even if you don’t intend to be one.”

And racism? It’s not one thing but many.

It’s a system of advantage based on race, scholars say. It’s a collection of stereotypes, prejudices and discriminatory behavior. It’s overt and covert. And it operates across an individual, group and societal level.

The truth? Everyone has some racist attitudes

Here’s the bad news if you are one of those people asking, “Am I racist?”

“If you have to ask if you are a racist, you are,” says Angela Bell, an assistant professor of psychology at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania. “And if you are not asking if you are a racist, you are.”

Bell’s paradoxical response is part of what she and others say about racism: It’s almost impossible not to be a racist growing up in the US. If you think you’re immune from it, that denial itself is part of how racism perpetuates.

“You start off with the assumption that you are, because everybody living in the United States has internalized stereotypes about Black people,” says Mark Naison, an activist and a professor of African American Studies at Fordham University in New York City.

“One of the things I learned very early in my development is that everyone in American society internalized anti-Black attitudes because they are so ingrained in our culture,” he says.

Read more from John Blake:

That includes White liberals like himself, Naison discovered.

He was in a relationship with a Black woman for six years. Her family practically became his family because he spent so much time with them. One day he stumbled upon a research paper she had written in college. He started reading it and was surprised at how coherent and well-written it was – and then it hit him.

“I said, ‘Holy crap!’ ” he remembers. “I had internalized all of these expectations that Black people are intellectually weaker. I’ve got to work on myself.”

A lot of anti-racism work today leads to talk about “implicit bias,” or “racial bias.” Those are terms that describe how racial stereotypes and assumptions infiltrate our subconscious. People can act and think in racist ways without knowing it.

A classic example of this was a famous experiment in which researchers sent 5,000 fictitious resumes in response to employment ads. Some applicants had White-sounding names such as “Brendan,” while others had Black-sounding names, like “Jamal.”

The applicants with White-sounding names were 50% more likely to get calls for interviews than their Black-sounding counterparts.

Some scholars, though, have issues with terms like “implicit bias.” They feel it offers people an excuse to justify their racism by claiming, “My subconscious made me do it.”

“The term racial bias perpetuates the notion that racism is beyond your control, and that’s often not the case,” says Bell, the psychology professor. “People might not think that they have control over racism, and they can’t ever get rid of it. It’s absolutely within their control.”

It doesn’t matter if you voted for Obama

It can be fiendishly difficult, though, for people to see racism in themselves, says Bell, who studies how people fail to recognize their own racism.

Some of that is because of what psychologists call “moral licensing and credentialing.” Translation: A White liberal who brags, “I would have voted for Obama a third time if I could,” may be trying to signal that he or she is beyond racism.

In 2009, Stanford University researchers released a study which found that expressing support for Obama made some people feel justified in favoring Whites over Blacks.

Daniel Effron, who helped conduct the study, said at the time:

“This is the psychological equivalent of when people in casual conversation say something like, ‘many of my best friends are black.’ They say that because they’re about to say something else that they’re concerned might be construed as prejudiced.”

There’s also the tendency for people to evaluate themselves as superior to others, Bell says.

She cites an experiment she helped conduct in which she asked college students to fill out an online questionnaire asking if they had ever engaged in racist behaviors, such as using the N-word.

Months later, the same participants were asked to review similar responses from randomly selected students. The catch was that they were actually reviewing their own answers, but they didn’t know it.

“People evaluated themselves as less racist as the other person,” Bell says, “even though the other person was them.”

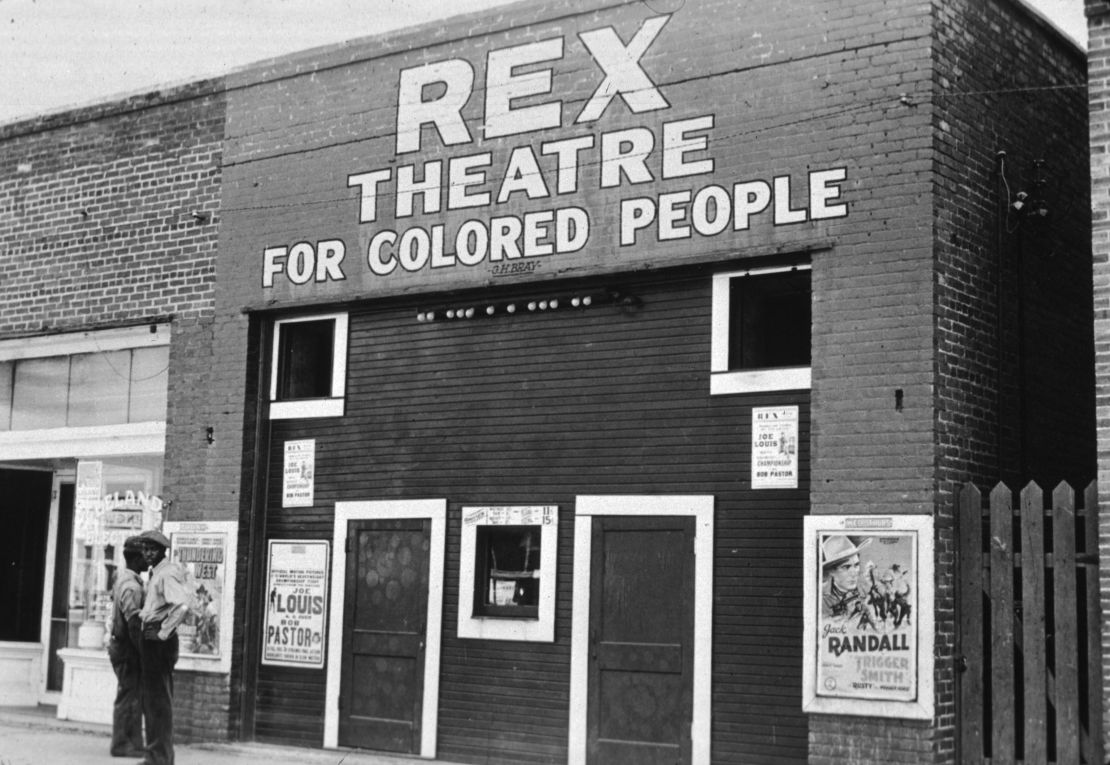

Individual racism isn’t as harmful as institutional racism

People have different ideas about how to get rid of racism. Some say the focus should be on institutional racism – in schools, policing, the workplace – and not on people’s feelings.

Reed says too many White Americans see “racism as psychology” – a naval-gazing definition that focuses on what people feel inside and personal displays of racial hostility, like racial slurs.

Reed says the goal of the civil rights movement was not to make White people better. It was to purge institutions of racism so that Blacks could have equal access to jobs, housing and education.

Not enough White Americans understand that racism is much more destructive when it infects an institution like the criminal justice system, he says.

“If you bring Mother Teresa out of the grave and put her in charge of any criminal justice system in any state,” he says, “she would be – unless she changed the system – the greatest practicing racist in the state.”

How to tell if you’re racist

A Google search for “Am I a racist” offers a quiz, but racist attitudes are too complex to diagnose like that. Naison, however, poses a few questions that may give you a clue.

Are you surprised when you meet a Black person whose command of language or speech or writing is of the highest order?

Do you assume that when you meet a Black person in an athletic competition that he or she will be stronger or faster than you?

Do you feel anxiety when a group of young Black men walk down the street toward you, or a twinge of fear when a Black man checks your gas meter or does home repairs?

If you answered yes to these you might be a racist, Naison says.

He adds that Black people who come in contact with you will probably know you’re a racist before you do. Blacks can often read White people’s body language when they’re experiencing these racist thoughts, he says. It could be something as simple as speeding up your walk when a Black man approaches on the street or hesitating to open your door when a Black man is ringing the bell.

Naison says a majority of Whites practice what he calls “aversive racism,” or engaging in behavior – some of it unconscious – “which lets Black people know they are uncomfortable around them.”

How to not be racist

One of the biggest obstacles to fighting racism is despair. There’s a belief that racism will never be eliminated because it always adapts to survive, and humans are too tribal to look past superficial differences in others.

But the modern framework of racism – a racial hierarchy with White on top and Black on bottom – is a relatively recent fabrication. The notion that people with darker skin are inherently inferior was contrived around 500 years ago by Europeans to justify slavery and colonial conquest, scholars say.

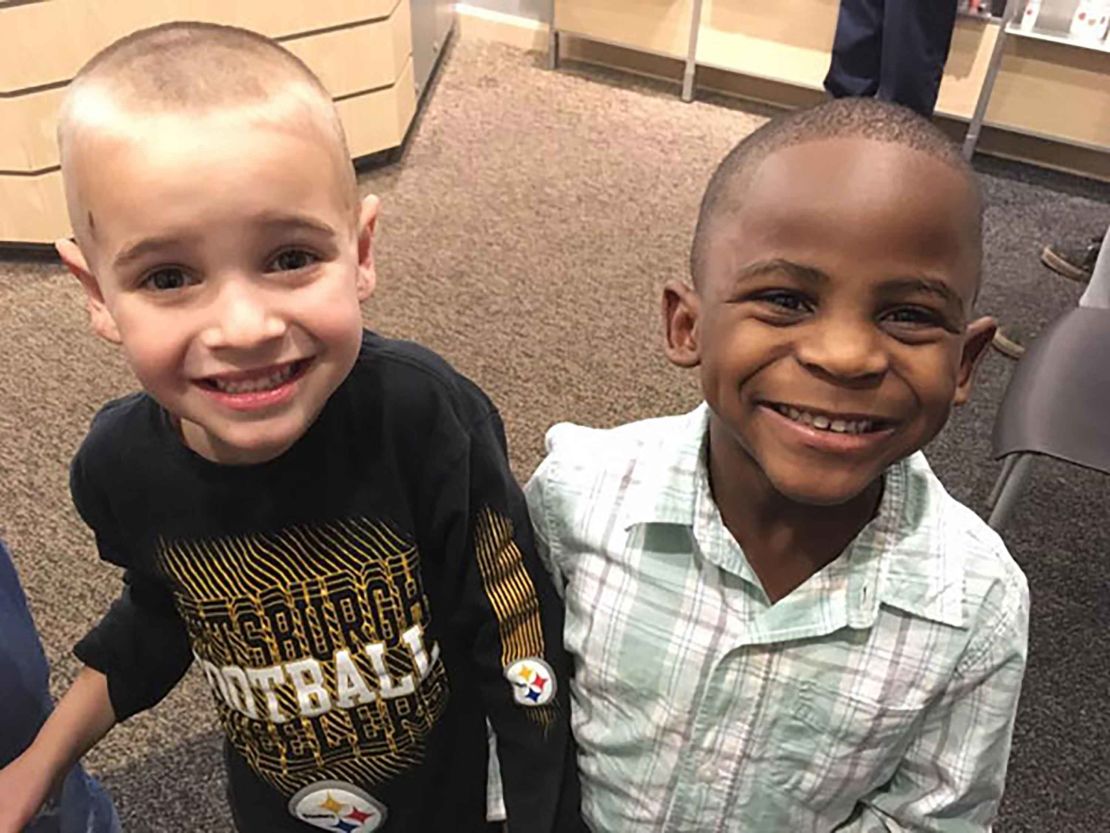

History lessons won’t prevent someone from being a racist. But something else can: genuine, sustained personal relationships with people of color.

“Reading books is a good thing, and participating in study groups is fine, but making your social networks genuinely diverse is critical,” says Naison, the Fordham professor. “You can’t live in a White bubble.”

Most White people, however, are socially isolated from people of other ethnicities, he says. Naison says he goes to the homes and celebrations of White friends and hardly ever sees any people of color.

“And these are people who support every possible justice issue, and who march in Black Lives Matter protests,” he says.

Naison says he’s never had to ask Google, “Am I a racist?” because his world is full of people of color who will tell him if he is being a racist.

“I’ve had a great life and I’ve learned to make this happen,” he says. “If I can do it, you can too.”

Maybe starting that journey begins with a less self-centered question for Google.

Instead of “Am I racist?” ask yourself:

What am I doing to stop the racism I see in the world?