Early on Sunday morning, the mutilated body of a 42-year-old woman was found in Eersterust, a middle-class township in Pretoria, South Africa.

Two days earlier, residents in the Soweto township of Johannesburg discovered the body of another young woman under a tree. And just over a week ago, a heavily pregnant 28-year-old was found hanging from a tree on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

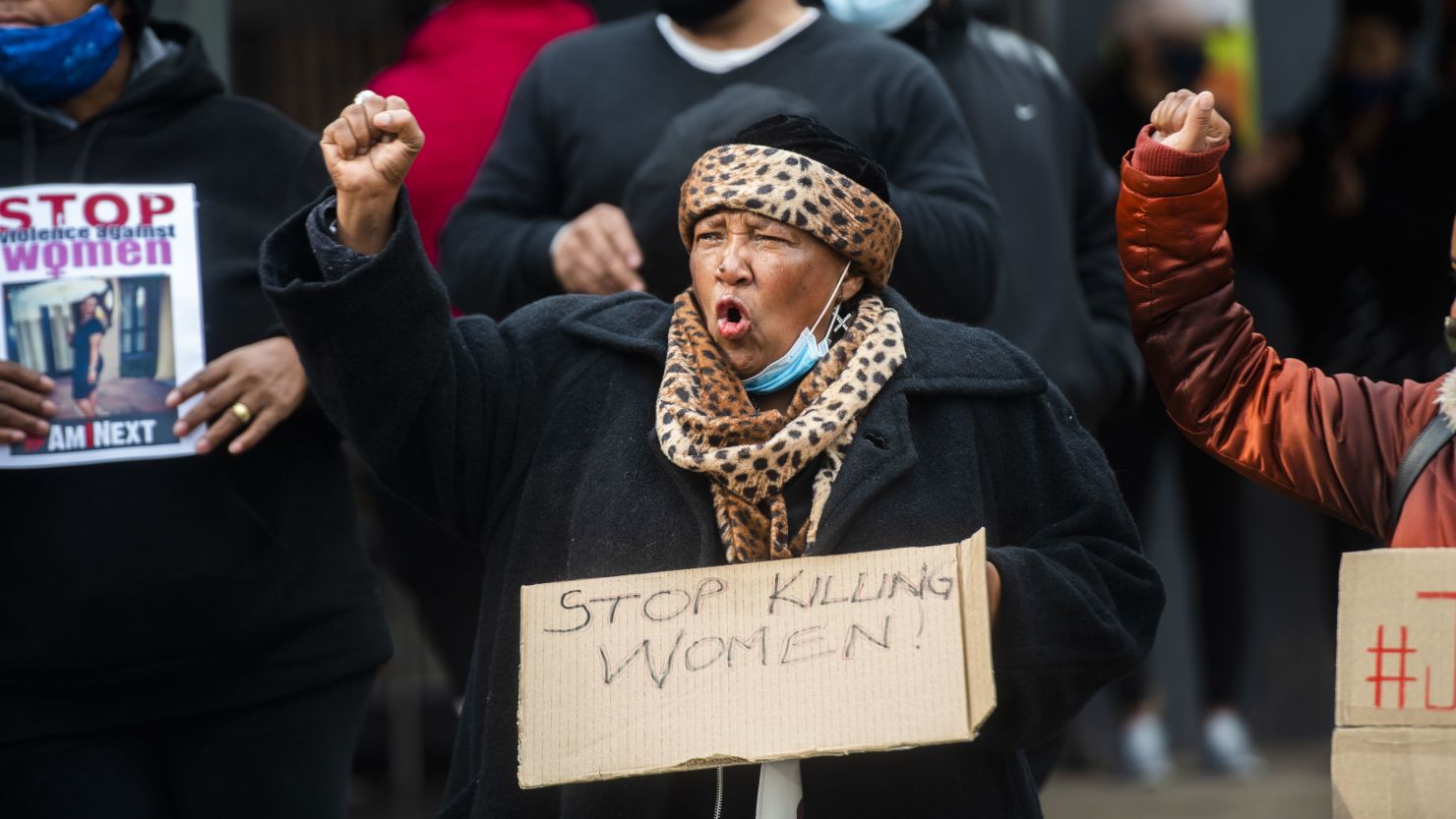

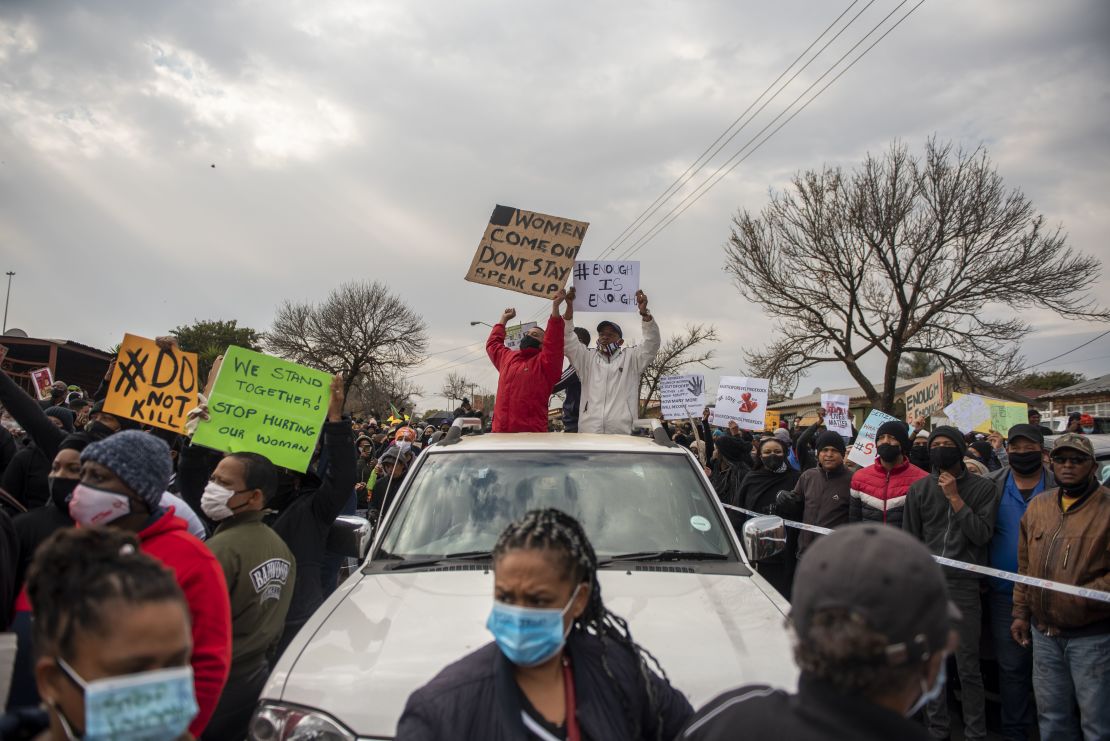

The three women were among the latest victims in a surge of violence against women in South Africa which the country’s president has described as a “pandemic.

“As a man, as a husband, and as a father, I am appalled at what is no less than a war being waged against the women and the children of our country,” said President Cyril Ramaphosa in a nationwide television address Wednesday.

More than 20 women and children have been murdered in South Africa in recent weeks, he added. “These women are not just statistics, they have names, they have families and friends,” he said as he read out the names of the victims.

In an earlier statement on Saturday, he said the killings show that perpetrators have “descended to even greater depths of cruelty and callousness.”

South Africa has one of the highest femicide rates anywhere in the world. More than 2,700 South African women and 1,000 children were killed last year, according to police figures.

According to Ramaphosa, around 51% of women in the country have experienced violence at the hands of their partners. Cases have spiked since the country eased some coronavirus lockdown restrictions in June.

“We note with disgust that at a time when the country is facing the gravest of threats from the pandemic, violent men are taking advantage of the eased restrictions on movement to attack women and children,” the President said.

Fatimata Moutloatse, founder of the Black Womxn Caucus said South Africa had been battling with issues of gender violence, inequality, and unemployment, and the pandemic could push the nation to the brink.

“We have a crisis, and the lockdown restrictions are amplifying it,” Moutloatse said.

‘We want accountability’

In September 2019, Ramaphosa announced measures to tackle violence against women following the rape and murder of university student Uyinene Mrwetyana in a string of femicide cases.

Mrwetyana had been sexually assaulted and killed in a Cape Town post office. Her death sparked widespread protests and re-ignited the conversation around gender violence.

In response, Ramaphosa pledged $75m to strengthen the criminal justice system and provide better care for victims. In his Wednesday address, he also called on lawmakers to process a series of amendments including minimum sentencing, and stiffer bail conditions for perpetrators.

Only justice and the swift prosecution of cases will demonstrate that government commitment to women’s safety, women rights activist Ngaa Murombedzi, from advocacy group Women and Men Against Child Abuse, told CNN. “It’s not enough for the president to say we won’t tolerate violence. We want accountability. The government cannot just be saying they are taking a strong stance when they’re not acting. They need to put action with those words,” Murombedzi said.

Deep-rooted problem

But Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, Minister for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities, says the South African government alone cannot tackle the crisis alone.

Nkoana-Mashabane said authorities also need the help of communities to end the silence around gender violence and expose abusers.

“We are aware that this fight is bigger than the government, and we need communities to helps us curb this epidemic. Communities can play a big role in curbing this epidemic by reporting incidents of abuse to local organizations, and South African Police Service (SAPS),” Nkoana-Mashabane said.

Police spokesman Kay Makhubela agrees.

Makhubela said women need to report aggressive partners to the police.

“If people see there are signs of aggressiveness and violence, they must report to the police before incidents like this happen. Immediately they see signs of danger, they must report it,” Makhubela told CNN.

But some experts say a culture of domestic violence is deep-rooted in South Africa’s apartheid era where women and children faced high levels of violence and that criminal justice and policing systems alone cannot fix the problems.

Gareth Newham, Head of the Justice and Violence Prevention program at the Institute of Security Studies told CNN not much will change as long as men hold onto patriarchal beliefs that suppress women.

“Now, we need programs for men at their early childhood that educate them about different attitudes and they’ll see women as their equals and will be less likely to use violence at all when they grow up,” Newman said.

CNN’s Brent Swails and journalist Nyasha Chingono contributed to this report.