It’s a common rule in Asian American households: Don’t bring home a black boyfriend or girlfriend.

And it’s an order many young Asian Americans ridicule or challenge when talking with their parents. But it helps illustrate the racism and anti-blackness characteristic of some older Asian immigrants.

Joyce Kang, a 30-year-old Korean American from Washington, D.C., has heard her friends share similar experiences.

“Dating or marrying a black person is not preferred within the Korean community,” Kang told CNN. “People have heard that said to them directly from their parents.”

But George Floyd’s death and nationwide protests supporting the Black Lives Matter movement have helped change the discussion. Young Asian Americans are increasingly engaging in difficult conversations with their parents and community about uprooting their anti-black sentiments and supporting African Americans.

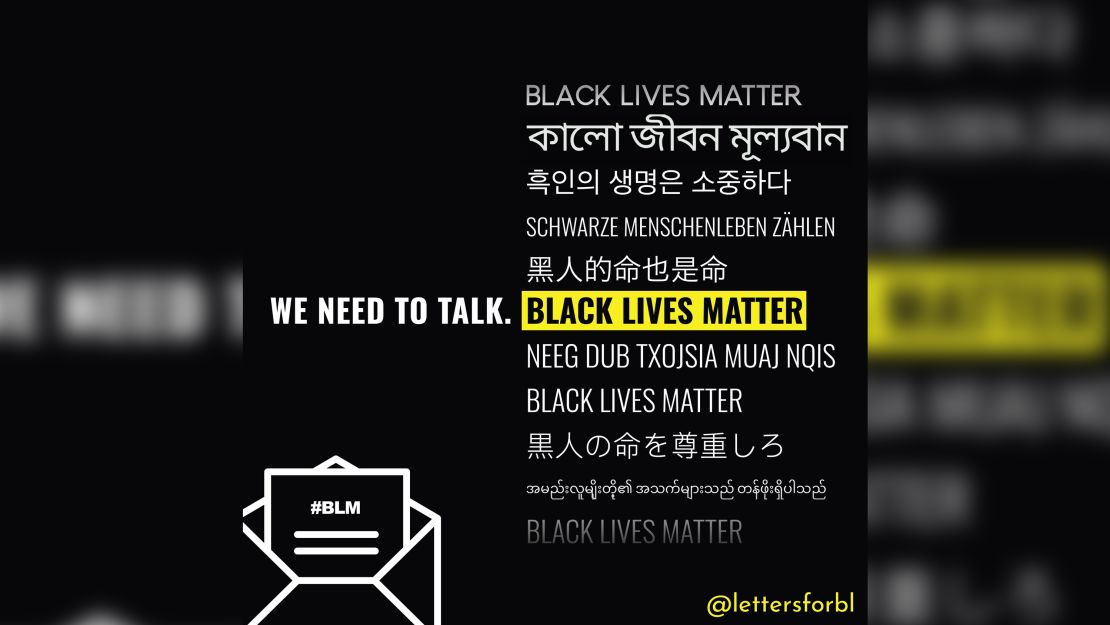

Kang decided to help by joining the “Letters for Black Lives” project and translating the open letter into Korean.

The letter was written in 2016 after the shooting of Philando Castile, a black man who died during a routine traffic stop. Recently, however, it has been rewritten to include Floyd’s death and to better reflect the current state of the nation.

“Mom, Dad, Uncle, Auntie, Grandfather, Grandmother,” the English version of the letter begins. “We need to talk. You may not have many Black friends, colleagues, or acquaintances, but I do. Black people are a fundamental part of my life: they are my friends, my neighbors, my family. I am scared for them.”

Kang is one of the more than 330 people who helped translate the letter into 26 languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Khmer, Lao, Nepali, Tagalog and Burmese. Each version varies because translators have incorporated different racial issues that are specific to their communities.

“The whole spirit behind this is that it is very much a template for how to help other people have these conversations,” said Adrienne Mahsa Varkiani, one of the project’s administrators who translated the letter into Persian. “We really encouraged translators to make it something that makes sense for your community.”

The letter directed at South Asians mentions their own feelings of discrimination and violence after 9/11, “When members of our community were blamed for ‘bringing terrorism.’”

The Korean letter acknowledges the “protest and struggle” felt by South Korea under 35 years of colonial rule by Japan.

But all the letters connect these different experiences of oppression to African Americans and the sometimes violent discrimination they face.

“The Asian American community does not experience the systemic racism that the black community faces,” Kang said. “I acknowledge that these conversations are difficult and hard to have within our own homes… (But) we are still in a position of privilege that it’s a choice to have these discussions, whereas black families need to have these conversations because of safety and real lived experiences.”

The letters have been shared widely on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. And both Kang and Varkiani say they have heard stories of how the letters have opened up this difficult dialogue between different generations.

Yulan Lin, a software engineer from California, shared the letter with her grandfather, who grew up in Japanese-occupied Taiwan and only heard the “American exceptionalism version of US history.”

“Over the weekend, my sister went through the Japanese version of @LettersForBL with my Grandfather, and something clicked in him,” Lin tweeted.

“He started seeing racism in America as a systemic human rights issue. On Tuesday, he asked me follow-up questions. We started revising his understanding of American history; more specifically deconstructing the myths that: 1) Racial discrimination ended after slavery 2) The USA is an equal opportunity country,” Lin wrote.

A newsletter for Asian aunties and uncles

Kavya Balaji and friends Shilpa Bhat, Shefali Mangtani and Audreela Deb came up with a digital newsletter as a way to talk to the aunties and uncles in their South Asian community about the Black Lives Matter movement.

The goal: To educate their community in a way that was easy to understand from the South Asian perspective.

“A lot of South Asian immigrant families, like my own, never learned US history or black history in the US because most of them were educated in other countries,” Balaji said. “So it makes sense that they didn’t already understand all the complexities of this movement.”

Balaji says most of the educational resources she’s seen on the Black Lives Matter movement are geared toward white people and critical of those who don’t understand the movement.

“I feel like a lot of non-black people of color see the movement as either a black issue as people who are directly affected by this or a white issue for people who have that history of oppressing black people,” she said.

To fix that problem for her community, Balaji and her friends launched the newsletter on June 1. The document is currently published in English, Hindi and Telegu. Gujarati and Tamil versions are in the works.

The letter, titled “Black Lives Matter: An informational letter to the South Asian community,” offers a brief history lesson, examining the civil rights movement, rioting and casteism. It also provides resources for making donations.

Balaji thinks of social justice as a ladder with people who are just starting to learn about it.

“In advocacy it’s important to understand where other people are at and think about things in an empathetic lens enough to deconstruct why people are thinking the way they are, what contributed to this frame of thought,” she said. “Then we can target those things and help them climb up that ladder.”

Balaji and her group want to make sure their letter helps the South Asian community become permanent supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Rewriting their narrative on Black Lives Matter

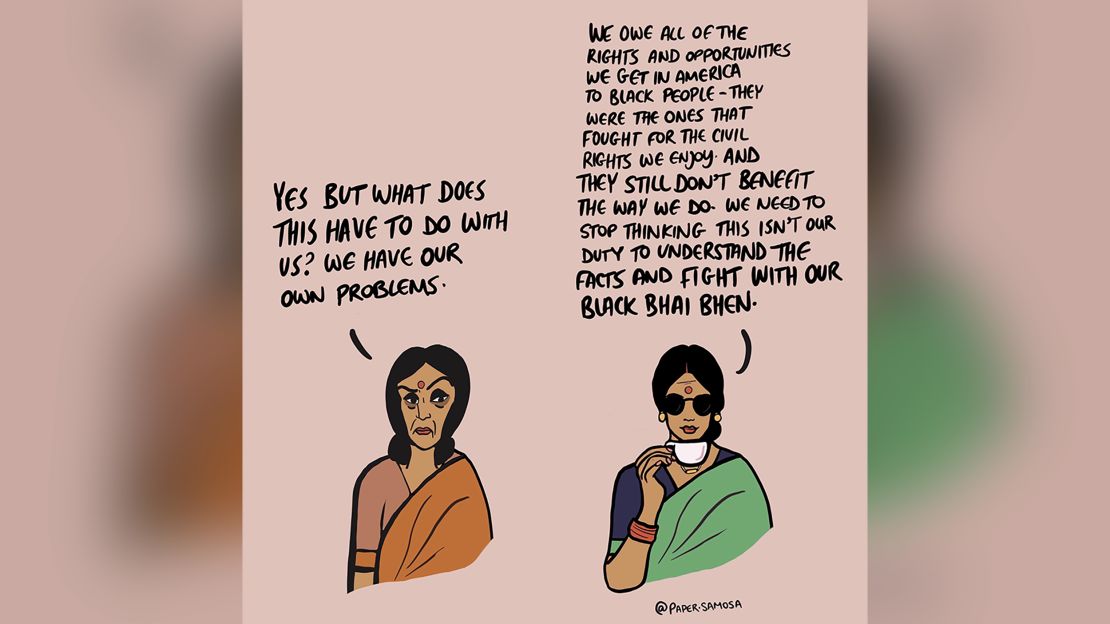

Simmi Patel is the brains behind Paper Samosa, an outlet that fuses South Asian and Western pop culture with colorful, meme-like posts and merchandise.

While Patel is usually crafting light-hearted content, she told CNN she wanted to figure out what to say, and how to say it, amid the current thirst for understanding.

In several Instagram posts, titled “It’s times for our South Asian mom’s, dad’s, aunties, and uncles to rewrite their narratives,” Patel creates a dialogue between two characters – emulating a conversation that many South Asians may find themselves having in their family group texts, place of worship or community gatherings.

“I think it was important to shake people up with these statements,” she said. “We can’t just turn away and say that this isn’t our problem.”

It was important to Patel to come at her illustrations from a place of understanding and compassion, coupled with factual statements, she says.

Six women established the California-based advocacy group South Asians for Black Lives in 2019. Its goal is to “amplify black voices and also increase efforts from the South Asian community to be better allies.”

Through social media posts and online resources, South Asians for Black Lives provides the building blocks for beginning conversations about confronting anti-blackness within neighborhoods and communities.

Haleema Bharoocha, a volunteer with the group, said the organization is working on a curriculum for the fall.

“There’s been a lot of people jumping from awareness straight to action without doing the work of education or self interrogation and really thinking about how to intentionally engage in sustainable allyship and not just show up for one protest,” she said.

‘Do this right’

The stereotype of Asians being the “model minority” has long been used to downplay racism and drive a wedge between Asian and black Americans, says Emily Chi, who recently graduated from the Harvard Kennedy School with a master’s in public policy.

“Our privilege and our proximity to whiteness and the lies that we believe about our model minority status has always been harming communities of color,” Chi told CNN. “(So) we’ve always had a responsibility to do this right.”

Chi and Joan Moon, a researcher at Harvard Kennedy School, worked with their colleagues to create the “Anti-Racism Resources for Asian Americans” toolkit. It’s a 20-page Google doc filled with different resources people can use to better educate themselves and their families.

From links, to articles about anti-blackness in Asian communities, to a video link on racial justice by Trevor Noah subtitled in Chinese, the document offers resources to help start a conversation, and it’s being viewed by dozens of users daily.

“It should not fall on black members of society to talk to other people,” Moon said. “Asians have to be talking to other Asians in order to create spaces to do the hard reflections that are required to release the burden on our black peers.”