Editor’s Note: Gautham Rao is associate professor of American and legal history at American University in Washington and editor-in-chief of Law and History Review. He is author of “National Duties: Custom Houses and the Making of the American State.” The views expressed in this commentary are the author’s. Read more opinion on CNN.

President Donald Trump pledged Monday to use the Insurrection Act of 1807 to deploy United States armed forces against protesters who have taken to the streets after the killing of George Floyd and the long history of racialized police violence against African Americans.

The way in which Trump made this announcement – against the backdrop of tear gas and militaristic action taken against protesters on his doorstep exercising their First Amendment rights – is itself a manifestation of unprecedented use of presidential power.

From a historical perspective, the act, which aimed to provide the mechanism for the federal government to quell an insurrection, is (along with its later amendments) one of the earliest and most significant accumulations of presidential power, dating back to the first years of the republic. But especially since the end of the Civil War, presidents have largely avoided invoking the act.

Since the 19th century, the United States has faced its fair share of crises. History teaches that presidents have treated the Insurrection Act with the greatest restraint, perhaps in keeping with what the late Justice Antonin Scalia described in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld as, “the Founders’ general mistrust of military power permanently at the Executive’s disposal.”

Of course, if we have learned anything in the past few years, it is that President Trump does not consider himself beholden to most traditions of presidential behavior. If he does array federal military forces against the American people for asserting their First Amendment rights, President Trump will imperil, if not destroy, the historic relationship between the presidency and the people. He will have made a national enemy out of the American people.

Like so much early United States law, the British Empire provided the precedent: the Riot Act. When colonists rioted – and they frequently did – law enforcement officials could read them the Riot Act before calling on the colonial militia to help restore order. The US Constitution gave the federal government limited enumerated powers while granting the states a far wider range of authority – including using their militias to contain insurrections. At the Constitutional Convention, the framers repeatedly expressed fears of a centralized, standing federal army. Ultimately, in Article I the framers gave Congress the power “To provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions.”

In 1792, with the country embroiled in wars with Native Americans, Congress used that power and President George Washington signed the Militia Act or Calling Forth Act. The 1792 law specified that in cases of insurrection, the president could command the state militia – the National Guard didn’t exist yet – to act if a state requested it. In cases of obstruction of the law, the president could act only if a federal judge explained that the resistance was “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

After President Washington used the 1792 law to quell the Whiskey Rebellion, in which Western Pennsylvanian farmers obstructed a new federal tax, Congress amended the law by removing the requirement of a federal judge to request intervention.

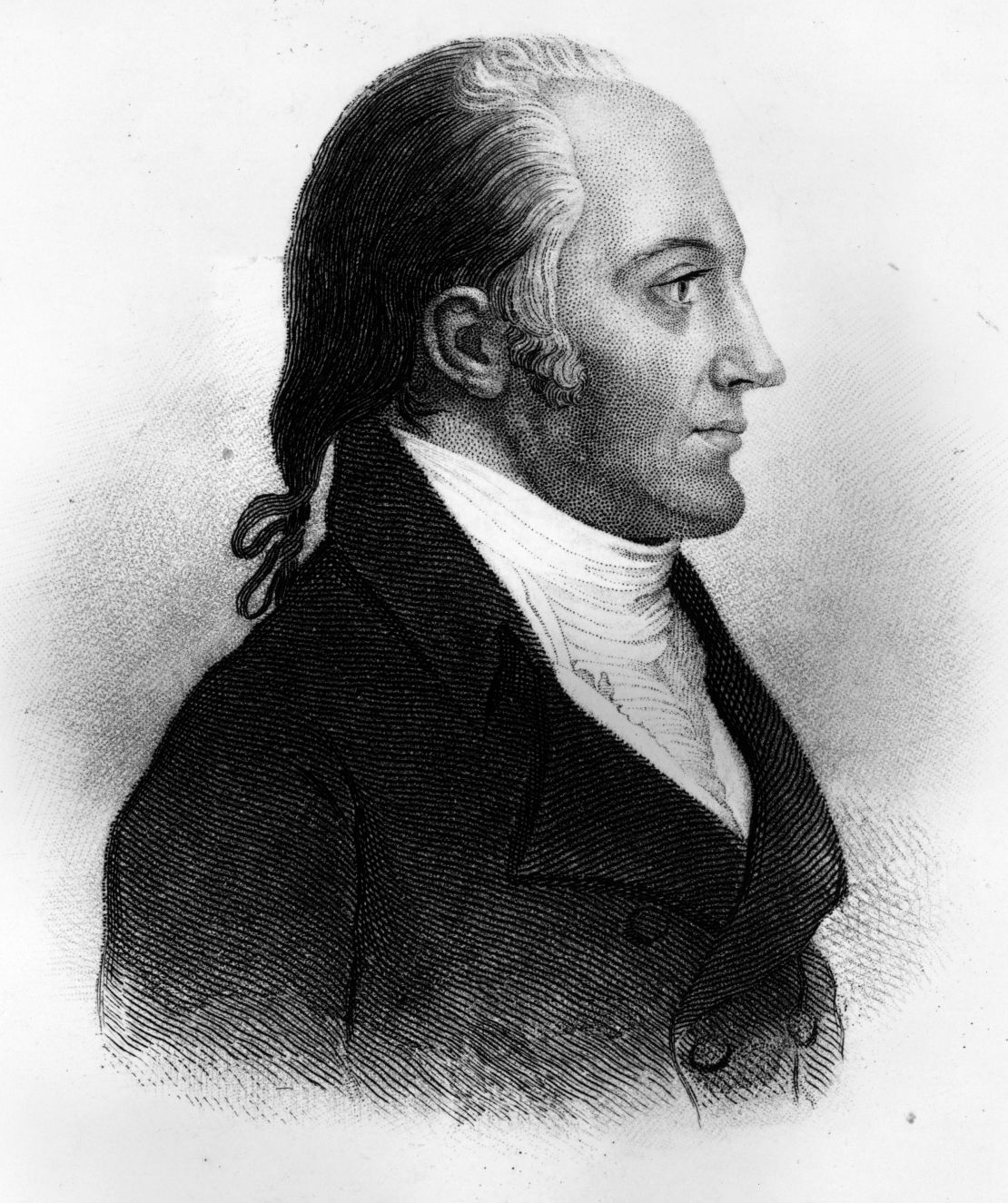

This brings us to the Insurrection Act of 1807. Aaron Burr, who has gained newfound currency through the musical “Hamilton,” played an important part. Burr’s mysterious political intrigues led to his arrest and prosecution for treason.

Though historians remain unclear as to whether Burr was plotting an insurrection as he traveled through the West for two years, President Thomas Jefferson then asked Congress for more authority to deal with insurrections.

The resulting law, the Insurrection Act, allowed the president to call on federal troops as well as state militias to put down insurrections. This was a momentous step. Only 20 years after the founding, the framers’ fears of a federal standing army had given way to the belief that presidents needed greater authority to use federal troops to police insurrections. Until the Civil War, the Supreme Court repeatedly confirmed the president’s authority under the Insurrection Act. Amendments to the Insurrection Act in 1861 and 1871 only further expanded the president’s authority to deploy federal troops or state militias.

The most notable ostensible impediment to the Insurrection Act is the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. Former Confederate leaders, who had returned to power, devised the act to prevent federal courts from using federal military forces to enforce Reconstruction-era laws that aimed to protect recently emancipated African Americans. Today, the law is understood as a prohibition on the use of United States armed forces “to execute the laws.” Yet Congress has carved lots of exceptions, including specifically authorizing the president to use National Guard and armed forces against insurrections. The Posse Comitatus Act is much more of a monument to Jim Crow than it is an actual barrier to use of the Insurrection Act.

History is the real barrier. Some experts think President Trump could invoke the Insurrection Act if: a state government asks for him to do so; he finds that protesters or others have made it impossible to enforce federal law; or a state is unable to protect constitutionally protected rights of its citizens. If he did so, he would be charting a very different course than most of his predecessors. In the broad sweep of modern American history, you can count on two hands the number of times presidents have turned to the Insurrection Act: For instance, President Eisenhower federalized the National Guard to desegregate schools during the civil rights movement, while President George H.W. Bush responded to California’s request and deployed federal troops there during the violence that followed the Rodney King verdict.

History has judged these decisions based on their ends. Dwight Eisenhower invoked the act to fight racial segregation and protect black students. George H.W. Bush’s decision to send the Marines to California was an unnecessary political decision to bolster his reelection effort by pandering to “law and order” voters.

President Trump now calls himself the “law and order president” as he ponders invoking the Insurrection Act while running for reelection. If he continues down this path, historians are likely to have a far bleaker assessment of his presidency. And of course, George H.W. Bush didn’t have to wait for historians’ verdict because the American people made their judgment clear on November 3, 1992.