During the Obama administration, high-profile police shootings of black men like Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and Laquan McDonald in Chicago helped spark sweeping federal investigations and reforms of biased policing practices.

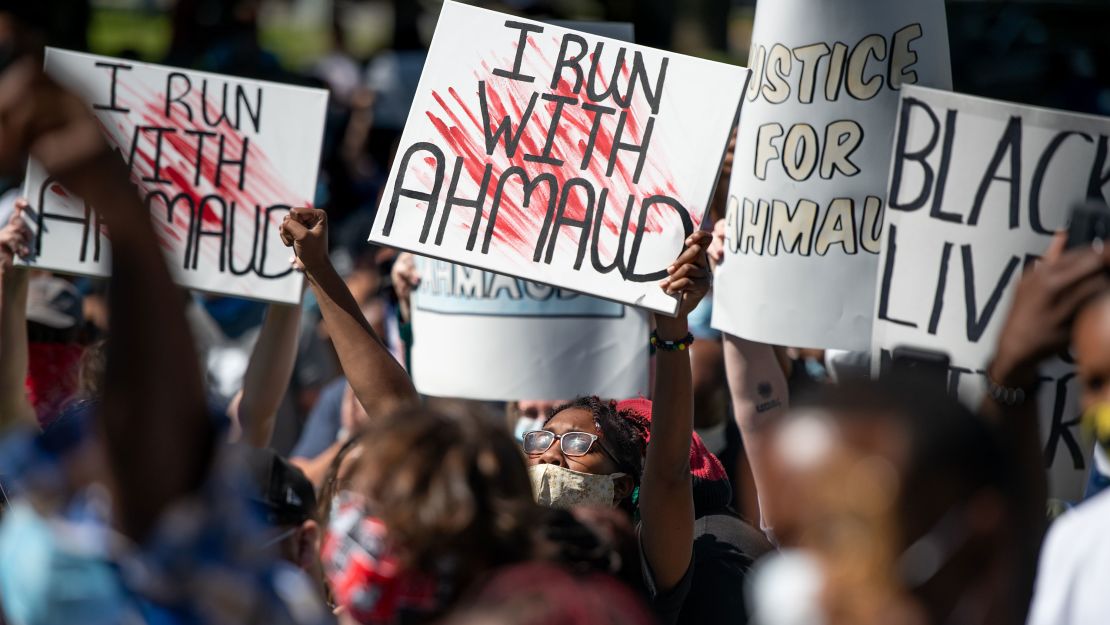

Now, a trio of wrenching deaths has again refocused the nation’s attention on the racial prejudices ingrained in the country’s justice system. Protesters have filled the streets in recent days demanding justice for George Floyd, who died as a Minneapolis policeman knelt on his neck; Breonna Taylor, who was shot dead by Louisville officers entering her home allegedly without announcing themselves; and Ahmaud Arbery, who was gunned down by two white men who went free for more than two months until a video of the small-town Georgia slaying went viral.

But under President Donald Trump, the Department of Justice has all but abandoned broad investigations into unconstitutional policing practices, a half-dozen former DOJ lawyers who worked on similar cases told CNN – essentially giving up on one of the federal government’s most effective tools to fight police misconduct.

While the Justice Department launched 12 investigations of law enforcement agencies for practices that violate the Constitution during George W. Bush’s first term, and 15 during Barack Obama’s first term, the department has opened only a single public investigation of that kind in the three and a half years since Trump became president, according to legal experts and DOJ records.

In the wake of the outrage in Minneapolis and around the country, “the DOJ is needed more than ever,” said William Yeomans, who spent 26 years at the department prosecuting cases involving police misconduct and hate crimes. The DOJ should “examine the Minneapolis Police Department from top to bottom, every detail, every practice, every policy, every record of abuse of its power to use force, every complaint that has ever been launched against it,” he said. “But it isn’t going to do that.”

The Justice Department has announced more limited investigations into several of the recent deaths. The US Attorney for Minnesota said last week that an investigation into the officers involved in Floyd’s death was a “top priority,” and a lawyer for Arbery’s family told CNN that federal officials had informed the family they intend to investigate the men who chased and shot him for possible hate crime charges.

“I am confident that justice will be served” in the Floyd case, Attorney General William Barr said in a statement Friday, calling the video of Floyd’s death “harrowing to watch and deeply disturbing.”

Activists and elected officials have been calling for broader investigations. On Thursday, Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee wrote to the DOJ to demand investigations into the Minneapolis and Louisville police departments’ practices, and a probe of why Georgia officials took so long to make an arrest and file charges in the Arbery shooting. Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and 27 of her Democratic Senate colleagues have also called for a DOJ investigation into the Minneapolis department’s practices.

But former DOJ attorneys said they doubt Barr would be interested in such wide-ranging cases. And even if investigations were opened, a department policy put in place by Barr’s predecessor, Jeff Sessions, severely restricts prosecutors’ ability to seek consent decrees, court-enforced agreements with police agencies that mandate reforms.

A DOJ spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about the department’s use of police investigations, or its plans to address the Floyd, Taylor and Arbery killings.

The Trump administration, police unions, and other groups representing officers have argued that the Obama administration went overboard in prosecuting police, harming officer morale and making departments less effective.

And in recent weeks, the department has cited the same legal authority that allows it to crack down on police misconduct for another target: stay-at-home orders. In at least two cases so far, the DOJ has supported churches that sued their state or city objecting to stay-home orders during the Covid-19 pandemic, arguing that the orders were being unfairly enforced against churchgoers.

“It’s an abdication of their responsibility,” said Emily Gunston, a lawyer who helped lead several DOJ investigations of police departments during the Obama administration. Without the department training its sights on law enforcement agencies, she said, “it means that there’s just no check on these police departments.”

A powerful tool to fight police misconduct

Congress gave the Justice Department the power to investigate biased policing practices in 1994, in the wake of the police beating of black Los Angeles motorist Rodney King and five days of rioting in the city when four of the officers were acquitted about a year later. A new law let the DOJ open investigations and file civil lawsuits against any law enforcement agency with a “pattern or practice” of violating constitutional rights.

Those investigations typically last months or years and involve holding public meetings, interviewing officers and community members, analyzing data about the local justice system and digging into case files. Ultimately, the DOJ can file a lawsuit to put in place a court-enforced consent decree, which would require a law enforcement agency to make specific reforms and allow a federal judge to monitor their progress.

Over the last two and a half decades, the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations collectively opened nearly 70 investigations of police departments and other law enforcement agencies around the country, leading to 20 consent decrees, according to DOJ documents and data compiled by The Marshall Project.

The power was used most aggressively under the Obama administration, which stepped up the use of consent decrees. Court-enforced agreements in cities like Ferguson, Cleveland and Baltimore included laundry lists of reforms departments agreed to comply with, from deescalation training and body cameras to changes in law and more equitable hiring practices.

One high-profile shooting isn’t enough to justify a pattern or practice investigation, former DOJ lawyers said – but sometimes cases that capture the national attention help cast a spotlight on more systemic defects, such as police departments’ excessive use of force or racially biased policies.

“You can’t look at one case in isolation,” said Sharon Brett, an attorney at Harvard Law School’s Criminal Justice Policy Program who worked on police investigations as a DOJ lawyer. “You’d have to show the constitutional violation occurring across more than one case.”

The Minneapolis, Louisville and Glynn County, Georgia, police departments have never been the subject of pattern or practice investigations. And activists in all three jurisdictions have argued that the recent high-profile killings aren’t isolated incidents but are examples of deeper-rooted problems.

In Minneapolis, a 2015 federal review conducted at the request of a former police chief found the agency faced “community perception of disparate treatment of communities of color,” “inconsistent” supervision of officers and flaws in how the agency flagged and tracked officers’ bad behavior. The Minneapolis Star Tribune reported in 2013 that none of 439 police misconduct cases handled by a then-newly opened office resulted in a single instance of discipline. And the officer who pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck had 18 prior complaints filed against him with the agency’s internal affairs division, according to the Minneapolis Police Department.

Former Chief Janee´ Harteau told CNN that every recommendation the DOJ made in 2015 resulted in change at MPD, including renewed training for supervisors and the development of a system that flagged any complaints against officers early, no matter how minor, and kept track of those complaints and resulting discipline or coaching. She also commissioned a 2017 DOJ review of how the police can better handle protests. Demonstrations erupted in that city in the wake of a 2015 shooting of a black man by two white officers.

One of the observations she said DOJ made was that police can do something simple to deescalate or at least prevent escalation during angry protests by simply not appearing confrontational. “If officers didn’t have to be in riot gear, we put them in polos and khakis,” she said. “And the city – everyone on down, council members, everyone in leadership has to train for an event like what you are seeing today in Minneapolis.” The city had begun to address that when the city’s mayor demanded her resignation in 2017 after a high-profile police-involved shooting. Harteau said she doesn’t know what training has happened since she left.

The Louisville Metro Police Department has faced multiple lawsuits alleging officers used race as a pretext to pull over black motorists and conduct “racially biased” seizures, as well as a scandal over two officers using a police department mentorship program to sexually exploit teenagers. A department spokeswoman said it does not comment about pending litigation.

And in Glynn County, a local grand jury declared in a report last year that the police department suffered from “an ongoing culture of cover-up, failure to supervise, abuse of power and lack of accountability.” The department has been engulfed in controversy involving alleged misconduct by a narcotics task force, which led to the police chief being indicted just days after Arbery was shot. (The chief, John Powell, has challenged the indictment and plans to plead not guilty, his lawyer told CNN.)

The Glynn County Police Department did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

Christy Lopez, a Georgetown Law professor and former DOJ lawyer who worked on police practice cases, said that she found it important to pay attention to local officials’ reactions after a high-profile shooting occurred.

“If the reaction is one of shock and surprise and an immediate attempt to figure out what happened,” it’s an indication that the incident might be an aberration, she said. But undue delays for law enforcement action after the Arbery and Taylor shootings could suggest “there might be tolerance for similar conduct more broadly,” she said.

Trump administration hits brakes on investigations

So far, the wide-ranging investigations and consent decrees that defined the Obama administration’s approach to police misconduct have all but disappeared under Trump.

Since the President took office, the department has made public only a single pattern or practice investigation, former lawyers and civil rights law experts say: an April 2018 probe of the Springfield, Massachusetts, police department’s narcotics unit. While two current and former officers were indicted on federal charges for unreasonable use of force against Latino juveniles later that year, the status of the broader investigation is unclear; a DOJ spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about its status.

Pattern or practice investigations into police departments are typically made public, according to DOJ documents, and former lawyers said it would be all but impossible to conduct a full investigation in secret.

Sessions spoke out against consent decrees and police investigations as attorney general, ordering a review of existing decrees and arguing that the cases “undermine the respect for police officers and create an impression that the entire department is not doing their work consistent with fidelity to law and fairness.”

Before Sessions left the department in November 2018, he put in place a memo that required consent agreements to be “narrowly tailored” to the injury caused by misconduct and limited the use of court monitors, among other stipulations.

The document “required attorneys to jump through ridiculous hoops in order to pursue a consent decree,” Yeomans said. It is essentially telling attorneys “you cannot pursue the most effective tool you have for reigning in police misconduct.”

While Barr hasn’t been as outspoken as Sessions about the issue, he said at his 2019 confirmation hearing that he generally supports the policies in Sessions’ memo.

The administration has also abandoned some of the cases that were started under Obama, including a high-profile investigation into the Chicago Police Department. Two weeks after dash-cam video of an officer shooting and killing black teenager Laquan McDonald was released in November 2015, the DOJ opened a pattern or practice investigation in the Chicago department’s use of force. That resulted in an extensive report on the department’s practices and an “agreement in principle” the feds and the city signed in the last days of the Obama administration agreeing that the two parties would move forward with a consent decree.

But after Sessions took over, the department decided not to move forward with pursuing a consent decree. In August 2017, then-Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan essentially stepped into the role left open by the department, filing suit against the city of Chicago, and later won a consent decree despite Sessions’ objections.

Under Trump, the department’s Civil Rights Division has continued to investigate conditions in prisons and juvenile justice systems, and has prosecuted individual malfeasance by law enforcement officers – which could continue with potential prosecutions of the officers in the Minneapolis or Louisville shootings. In addition to the Springfield case, the department sued the Baltimore County Police Department in August 2019 alleging that its hiring practices discriminated by race – but that case didn’t involve the county’s actual policing activity. And DOJ lawyers are continuing to help enforce consent decrees that are already on the books, legal observers say.

Meanwhile, the team that handled police practice cases saw numerous staff departures after Sessions made clear those investigations weren’t a priority, several former lawyers who worked in the group told CNN.

“The Trump administration has intentionally stripped its own capacity to address problems in local policing,” said Margo Schlanger, a University of Michigan law professor who tracks civil rights litigation. “They had all these tools… On some of them, they’ve cut off their own hands, on some they’ve tied their hands behind their back.”

The president himself has also seemed to encourage police misconduct. In a 2017 speech in New York, he told uniformed officers “please don’t be too nice” with suspects. “When you guys put somebody in the car and you’re protecting their head, you know, the way you put their hand over?” Trump said, making a motion with his hand to imitate an officer preventing a suspect’s head from hitting a squad car. “I said, you can take the hand away, okay?” His press secretary later said he was joking.

Early Friday morning, the president tweeted about the Minneapolis protests, threatening to send in the military and declaring “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” That’s a phrase that appears to have been coined in 1967 by a controversial Miami police chief who bragged that his department didn’t mind “being accused of police brutality” – although Trump said later Friday he didn’t know the phrase’s origins and hadn’t meant it as a threat.

Some police unions and officer advocacy groups have argued that the Obama administration went too far in its investigations of some police departments. Consent decrees hurt officer morale and made police departments less effective, and Sessions and Barr are right to reduce their use, they say.

Louis Dekmar, a former president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police and a police chief in Georgia, worked as a DOJ police monitor between 2004 and 2007 making sure that a police department in his state made federally requested improvements.

Given the number of problems at the Glynn County Police Department, he thinks the DOJ should conduct a sweeping investigation of its practices.

But he also said that the DOJ went overboard in attempting to institute changes in departments it investigated during the Obama administration. The DOJ “started mandating principles and philosophy like what kind of policing an agency should be doing, what constitutes community policing,” he said. “That’s why you saw the frustrations you did from police unions. It was too much.”

In contrast, he said, the Trump administration has given large grants to the police chiefs association to train officers, which Dekmar argued was an effective way to improve policing.

Still, activists say stronger federal oversight could help defuse some of the anger that has caused protests to devolve into violence in recent days.

When people lose confidence that police misconduct will be punished, “you have what’s going on right now: citizens operating out of order because the justice system hasn’t been operating in order,” said Rev. John Perry, the president of the local NAACP branch in Glynn County, where Arbery was shot and killed. “Part of securing the peace is showing our citizens we’re serious about accountability.”

From investigating police to challenging stay-at-home orders

Even as federal police investigations have all but disappeared, the DOJ has used the same statute that allows it to crack down on rogue law enforcement agencies for another target in recent weeks: Covid-19 stay-at-home orders.

In at least two cases so far, DOJ lawyers have backed lawsuits by churches against governments that are banning them from operating under restrictions on gatherings. Bans that are unfairly applied to churchgoers and not to people conducting other essential activities violate the Constitution, the department argued, citing the same law that bans police departments from systematically singling out people of a certain race.

So far, the department has weighed in on cases filed by local churches against Greenville, Mississippi, and the Democratic governor of Virginia, Ralph Northam. Federal lawyers also filed a brief Friday supporting seven Michigan businesses suing that state’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer, over her order, although they didn’t specifically cite the same statute.

Virginia “cannot treat religious gatherings less favorably than other similar, secular gatherings,” the DOJ wrote in its brief supporting an evangelical church that faced criminal charges after holding a service with 16 people. The department argued that the Northam’s stay-home order unfairly bans “church services or other religious gatherings that exceed ten people, despite permitting various other gatherings that may result from secular activities.”

The Virginia case is still being litigated, although a federal judge denied the church’s request for a temporary restraining order. The Mississippi lawsuit led the city to change its policy and allow drive-in services as long as churchgoers kept their windows rolled up.

Federal officials could get more involved in similar cases in the coming days and weeks, after Trump on May 22 said he was ordering governors to “allow these very important, essential places of faith to open right now” – a directive that legal experts said may not be enforceable.

Former DOJ lawyers say it’s ironic that the department is suddenly using the same statute it has all but given up on for police cases.

“They are using the police misconduct statute – for the second time in three years – in a case where plaintiffs are not even suing the police, but rather the Democratic governor,” Lopez said. “It certainly raises the question in my mind whether this is more about politics than police accountability.”

CNN’s Eliott McLaughlin contributed to this report.