A black version of the Chinese flag swept across African Twitter earlier this month, as users replaced their avatars to express their anger at the government of China.

They were outraged not only by widespread reports of coronavirus-related discrimination against Africans in China, but also by claims on Chinese state media that the allegations were “groundless rumors.”

Posting under the hashtag #BlackChina, Dennis Kiplomo, a nurse from Kenya, tweeted: “We expect the kind of hospitality we give to Chinese here in Africa, be reciprocated in their home country.”

Another user in Kenya, Peter Kariuk, wrote: “We need a united Africa which will not be slaves of #BlackChina.”

The southern Chinese city of Guangzhou has Asia’s largest African population. While the exact number of Africans living in Guangzhou is unknown, in 2017 more than 320,000 Africans entered or left China through the city, according to state news agency Xinhua.

Last month, many Africans were subject to forced coronavirus testing and arbitrary 14-day self-quarantine, regardless oftheir recent travel history, and scores were left homeless after being evicted by landlords and rejected by hotels under the guise of various virus containment measures.

The incident caused a rupture in China-Africa relations, with the foreign ministries of several African nations – and even the African Union – demanding answers from China.

Yet China’s official response stopped short of admitting that the discrimination took place – or apologizing for it.

“All foreigners are treated equally. We reject differential treatment, and we have zero tolerance for discrimination,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian. China’s embassy in South Africa said in a statement: “There is no such thing as the so-called discrimination against Africans in Guangdong province.”

The Global Times, a nationalist tabloid controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, went one step further, publishing an article titled: “Who is behind the fake news of ‘discrimination’ against Africans in China?”

Traditionally, Beijing has portrayed racism as a Western problem. But for many Africans, whose countries have in recent years become heavily economically entwined with Beijing, the Guangzhou episode exposed the gap between the official diplomatic warmth Beijing offers African nations and the suspicion many Chinese people have for Africans themselves.

And that has been a problem for decades.

No racism in China

The West only began really noticing – and criticizing – China’s relationship with Africa in 2006, following a landmark summit which saw nearly every African head of state descend on Beijing.

Yet China’s ties with Africa stretch back to the 1950s, when Beijing befriended newly independent states to position itself as a leader of the developing world andto counter US and USSR power during the Cold War era.

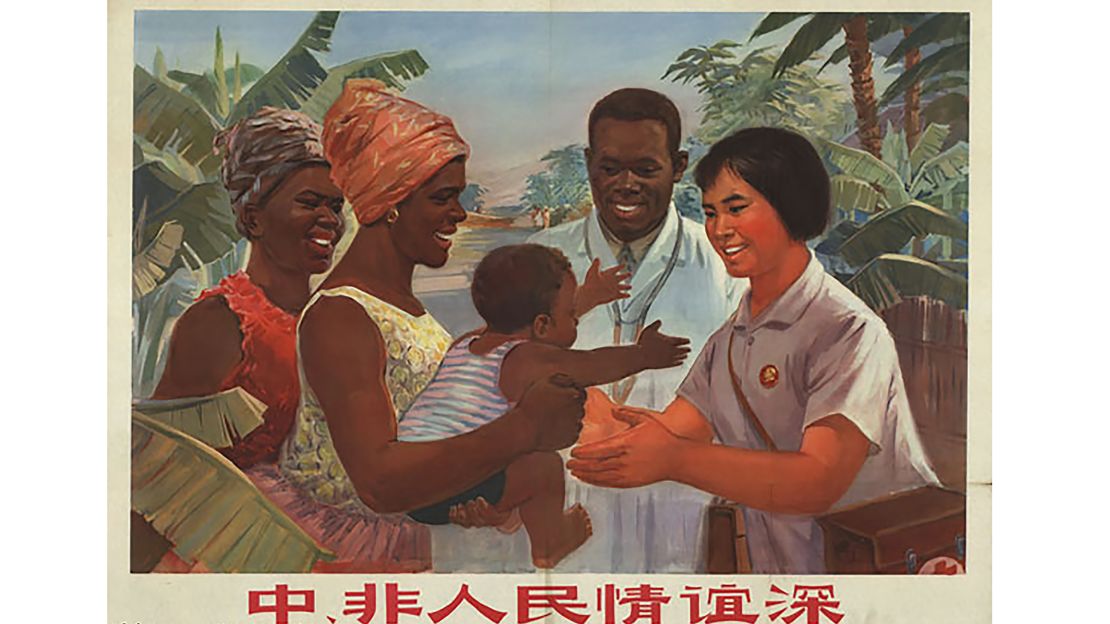

Beijing talked up its shared history of oppression by white imperialists, condemned South Africa’s apartheid early on and gave aid to Africa even when China was a poor country. In 1968, Beijing spent the equivalent of $3 billion in today’s money on constructing the Tanzam Railway in Zambia and Tanzania, and in the 1960s it began offering Africans full scholarships to Chinese universities.

The presence of African students in China was highly unusual.

Most foreigners fled China after the Communist Party came to power in 1949. When African students began arriving in significant numbers in the late 1970s, China was just beginning to open up to the world. The vast majority of people still lived in rural areas with no access to international media, and had not seen a black person outside of propaganda posters – let alone met one.

From the beginning, clashes were reported across the nation.

In 1979, Africans in Shanghai were attacked for playing music too loudly, leading to 19 foreigners being hospitalized. After another fracas in 1986, this time in Beijing, 200 African students marched through the capital, shouting that Chinese claims of “friendship were a mask for racism,” according to a New York Times report.

”The Chinese deceived us,” Solomon A. Tardey, of Liberia, told the newspaper. ”We know the truth now. We are going to tell our governments what the truth is.”

China’s then Education Ministry spokesman said: ”It is the consistent and long-term policy of the Chinese government to oppose racism.” That response wasechoed nearly word for word in a statement from the Chinese government responding to the fallout in Guangzhou last month.

A race riot in China

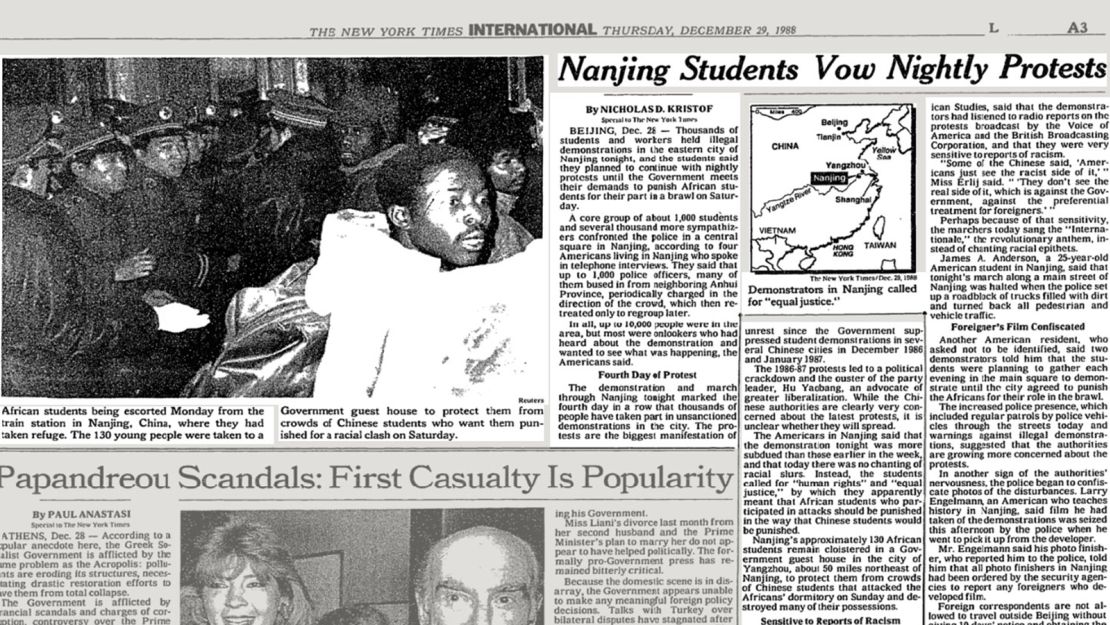

By 1988, a total of 1,500 of the 6,000 foreign students in China were African, and had been scattered to campuses around the country – a tactic designed to dilute racial tensions, according to a 1994 report by Michael J Sullivan in China Quarterly magazine.

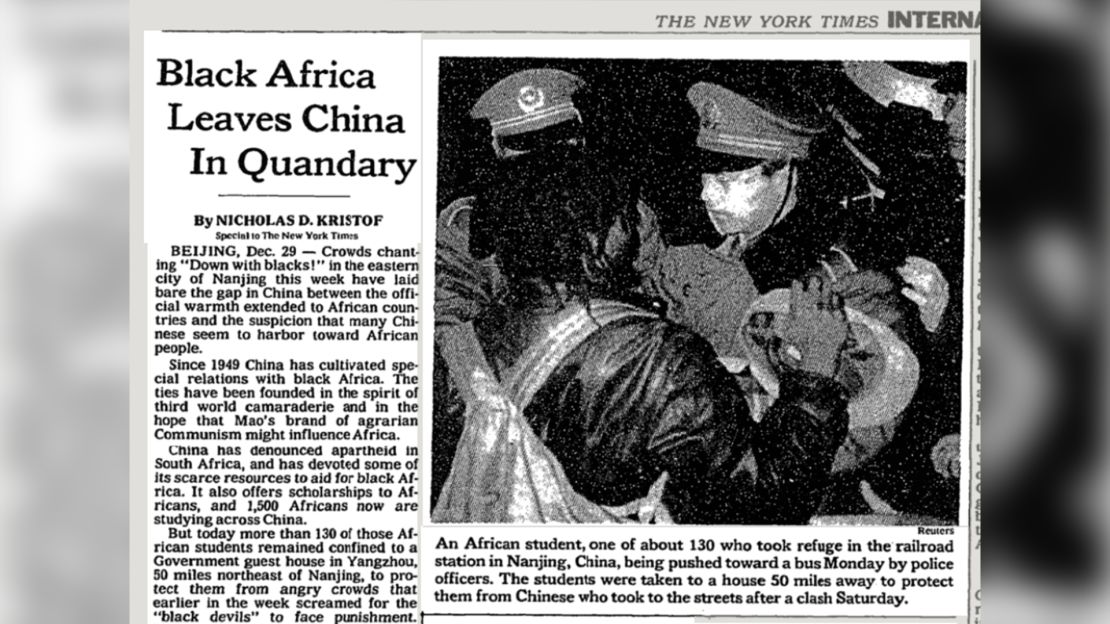

But the attempt didn’t work, and on Christmas Eve that year anti-black tensions exploded in the eastern city of Nanjing, resulting in a mob of Chinese protesters running the Africans out of town.

After, the Chinese government claimed that African students had arrived at a campus dance armed with weapons, including a knife, and beat up Chinese guards, teachers and students after being asked to register their Chinese guests, according to the Jiangsu provincial yearbook.

The Africans maintained that when they tried to bring a Chinese friend into the dance, they were taunted with calls of “black devil” and a fight ensued, according to Sullivan.

Whichever account is true, what happened after has been well documented.

Later that night, about 1,000 local students surrounded the Africans’ dormitory, after rumors swept campus that they were holding a Chinese woman against her will. Chinese students lobbed bricks through their windows.

After police broke up the scene on Christmas Day, about 70 African students decided to flee the campus and went on foot to the city train station, hoping to travel to Beijing where they had embassies. Other dark-skinned foreigners, including Americans, also fled, fearing for their safety.

On campus,rumors spreadthat the Chinese hostage had died.

At 7 p.m. on Christmas Day a mob of about 8,000 students from universities across the city began marching to the railway station, carrying banners shouting “severely punish the murderer” and “drive out black people.”

As the mob closed in, police bussed out all the black students to a nearby guesthouse, where they were held until several Ghanian and Gambian students were arrested for the fight at the campus dance.

The other Africans were bussed back to campus – and warned not to go out at night.

Kaiser Kuo, an American-born Chinese guitarist in the Tang Dynasty rock band, and founder of media group Sup China, was studying at Beijing University of Language and Culture that Christmas, living on a dormitory floor with students from Zambia and Liberia. He remembers hearing about the race riots.

“They were angry with the Africans that apparently a Chinese woman’s honor had been sullied,” he said. “This is one of the things where the rumor just kept getting inflated. By the time it reached my ears, the version was that a Chinese girl had been raped to death, when of course there was no evidence of anything like that ever happening.

“As far as I can tell, it was more like an African man had asked out a Chinese girl.”

Anti-African protests

The Nanjing event was not an outlier. In the city of Hangzhou, students claimed Africans were carriers of the AIDs virus in 1988, even though foreign students had to test negative for HIV before entering the country, wrote Barry Sautman in China Quarterly.

Then, in January 1989, about 2,000 Beijing students boycotted classes in protest against Africans dating Chinese women – a recurrent lightning rod issue. In Wuhan thatyear, posters appeared around campuses calling Africans “black devils,” and urging them to go home.

Kuo remembers: “You know, all around me, there was this real concern among the African students for this kind of rising xenophobia on the college campuses.”

That created a problem for Beijing, Sautman wrote, as it undermined China’s credentials as the leader of the developing world – and the hostilities didn’t go unnoticed back home.

Just as African media across the continent was outraged by the Guangzhou incident in April 2020, newspapers in Africa reacted with indignation in the 1980s. A Kenyan publication said they were not “accidental,” wrote Sautman. A Liberian newspaper spoke of “yellow discrimination.” A Nigerian radio station said the Chinese students “could not bear to see Africans” mix with Chinese girls.

The Chinese ambassador to the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union, was called in to answer for what was happening in China, and the OAU secretary general called it “apartheid in disguise.”

Many African students left China as a result. Around the same time, China announced a reduction in interest-free loans for Africa, marking a cooling off of official relations, although ties were never broken.

Now a professor in social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Sautman says that while the anti-African protests during the late 1980s were about race, they were also a way for Chinese students to express broader anti-government sentiment.

“The people who participated in anti-African demos then were university students, and those students were in some ways jealous of the African students,” he says.

The Africans typically got their own room, whereas Chinese were often living eight to a dorm.

“They perceived them as living better than they did because they got subsidies from their home government and the Chinese government, and they also thought that Africans acted in a freer way than Chinese students were allowed to act,” Sautman says.

Is Chinese racism the same as Western racism?

As China’s interaction with African people increased in the 21st century, the awkward gap between the public friendship Beijing extends and the private suspicion its citizens harbor has once again sparked moments of racial tension.

In 2009, an African-Chinese contestant on a Shanghai TV talent show received a barrage of internet abuse because of her skin color. In an opinion piece in the state-run China Daily, columnist Raymond Zhou argued that this discrimination stemmed from the fact that “for thousands of years, those who worked outdoors (had darker skin and) were of the lower social status” – rather than racism.

“Much of China’s simmering intolerance is color based. It is not an exaggeration to say many of my countrymen have a subconscious adulation of races paler than us,” he said.

“(It seems like) outright racism, but on closer examination it’s not totally race based. Many of us even look down on fellow Chinese who have darker skin, especially women. Beauty products that claim to whiten the skin always fetch a premium. And children are constantly praised for having fair skin.”

But more recent events have undermined the idea that discrimination against black people in China is not racism.

In 2016, a Chinese detergent maker sparked international outrage over an advertisement that showed a black man being washed whiter in order to woo an Asian woman. A spokesperson for the company said Western media was being “too sensitive.”

The following year, a museum in the city of Wuhan apologized for presenting an exhibition that juxtaposed images of African people and wild African animals making similar facial expressions. Then, in 2018, the annual gala for national broadcaster CCTV drew ire after a Chinese woman appeared in black face.

In Africa, where it is estimated more than 1 million Chinese people now live, there have been repeated reports of Chinese restaurateurs setting up establishments that ban Africans.

“There is a classic discussion over whether Chinese racism is racist in the way it’s envisioned in the West or Europe, or is it a different kind of discriminatory policy,” says Winslow Robertson, founder of Cowries and Rice, a China-Africa management consultancy.

“My sense is that it is racism. Is it identical to what we see in the US coming out of chattel slavery? No. But if you define racism as based on something you can’t change about yourself, then yes it is racism.”

Discrimination against Africans in China during the coronavirus pandemic, he adds, has exposed that fact.

Earlier this month, in a bid to head off those criticisms, officials in Guangdong announced new measures to combat racial discrimination, including setting up a hotline for foreign nationals. The notice said that shops, hospitals, restaurants and residential communities – the places where Africans had been targeted – should offer “strictly offer equal services.”

But Paul Mensah, a Ghanian trader who has been living in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen for five years, says the treatment of Africans in China during the Covid-19 pandemic has shaped his perceptions of racial attitudes in the country.

“I thought racism was inherent in America but I never thought people in China would do this,” says Mensah. “Before when they (Chinese people) would see a black person, they would touch your skin and touch your hair, and I thought it was out of curiosity because a lot of them don’t travel. But this is racism and there is no punishment for it.”

Sautman, who wrote the paper on the Nanjing riot, says that if China is serious about eliminating the maltreatment of foreigners, it should punish those who mete out racial abuse and discrimination.

Article 4 of China’s constitution stipulates that “all ethnic groups in the People’s Republic of China are equal … discrimination and oppression of any ethnic group is prohibited. It is forbidden to undermine ethnic unity and create ethnic divisions.”

But there have been no reports of people in Guangzhou being held accountable for their actions against Africans, and the constitution has had little effect in protecting China’s own ethnic minorities. It is estimated that 2 million of China’s Uyghur minority are being held reeducation camps in the northwest of the country.

Without an enforced legal deterrent, Sautman says it will be hard to change the way Chinese people treat Africans. “There’s not a place in the world where racial discrimination has been diminished without taking those actions,” he says.