Editor’s Note: Michael Bociurkiw is a global affairs analyst, a former spokesman for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and host of the podcast Global Impact. Follow him on Twitter @WorldAffairsPro. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his; view more opinions on CNN.

The World Health Assembly (WHA) – the biggest event on the global health agenda – held on Monday and Tuesday this week, can be easily summed up: The Trump administration threatened to take the UN agency off life support as it fights a global pandemic – and Chinese President Xi Jinping threw it a new life line.

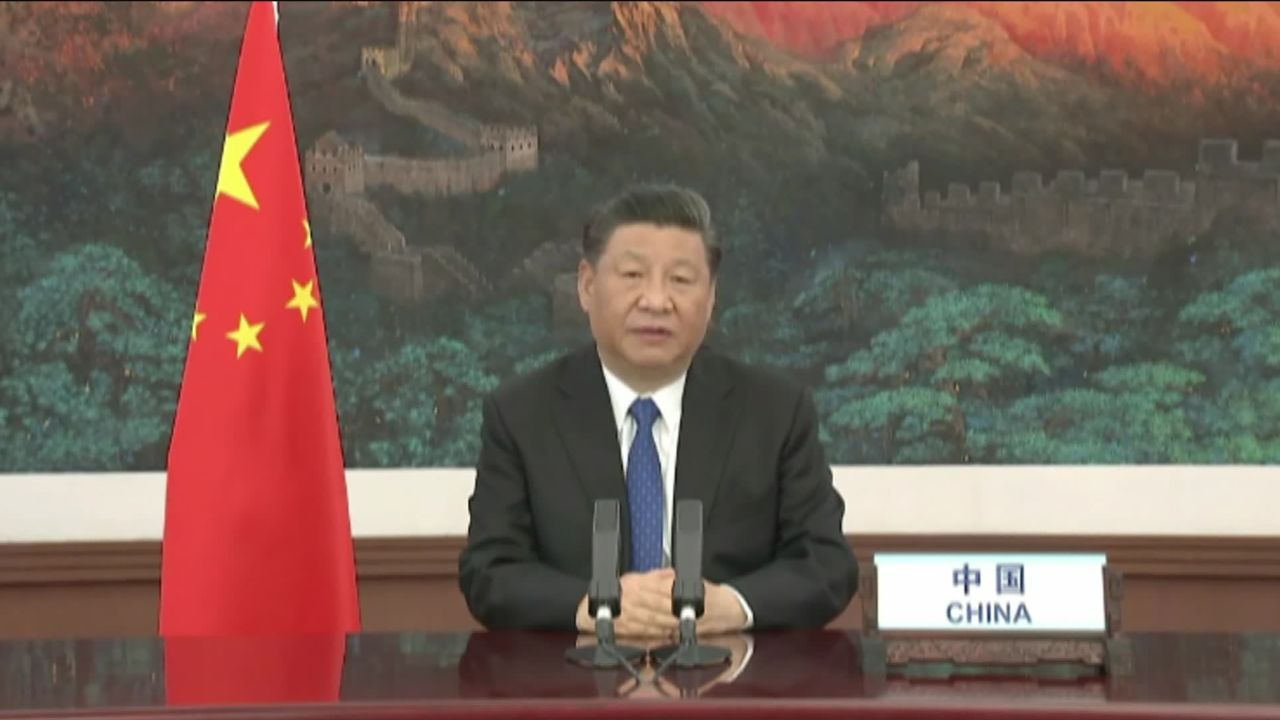

Xi – widely criticized for his government’s failure to sound the alarm over the situation in Wuhan, where the novel coronavirus outbreak began – was able to manipulate the 73rd WHA into a much-needed PR makeover for China. Meanwhile, the United States walked away, threatening to pull funding and membership from the World Health Organization (WHO) – potentially hobbling its ability to deliver a robust response to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

In a wider context, what we saw play out at the WHA was more proof of the Trump administration’s abdication of America’s traditional role as guarantor of globalization – and the unwitting creation of a void for the Middle Kingdom to exploit.

When he addressed the 194 member states by video, Xi pledged $2 billion over two years to fight the virus, a “humanitarian response depot and hub” in China, and assistance to the African continent to bolster their disease preparedness.

This pledge is important amid fears that Africa, with its congested cities and weakened health systems, would be at great risk for high rates of transmission.

China’s largesse also syncs well with its audacious efforts to woo African countries with billions in loans via its controversial Belt and Road Initiative.

As for the United States, its presence at the WHA was more of a cameo appearance with a locked and loaded Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. In a brief statement, he called out the failure of the WHO in its response to the pandemic and noted that that the organization must “become far more transparent and far more accountable.”

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump had his own plan for how to partake in the assembly. He sent a searing letter threatening to pull the United States from WHO membership and freeze funding should it “not commit to major substantial improvements within the next 30 days.”

The US is by far the largest contributor to the WHO, followed by China. Trump has criticized Beijing’s support for the UN agency, and one of his officials has already described the $2 billion pledge as “token.”

But token or not, the contribution is still vital for the organization, which has a $2.3 billion budget that the WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has called “very small” and comparable to “a medium-sized hospital in the developed world.” The executive director of the WHO’s health emergencies program, Dr. Michael Ryan, noted that the US funding pull will have “major implication for delivering health services to some of the most vulnerable people in the world.”

Whether the WHO, which battled a host of technical glitches during the WHA, can satisfy US expectations remains to be seen. For his part, Tedros pledged an evaluation of the WHO’s handling of the pandemic “at the earliest appropriate moment.”

America alone

Trump has already withdrawn the United States from other UN agencies – such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR) – and from such landmark agreements as the Paris climate accord. The latest threat to end US involvement in the WHO appears to be an attempt to divert attention from his own incompetent response to the Covid-19 outbreak, which, at the time of writing, has already infected more than 1.5 million Americans and killed more than 93,000.

My fear is that, even with a new administration, the process to restore America’s reputation and influence on the international stage may be slow: Perceptions evolve, alliances shift and politicians and professionals move on.

It is a sentiment shared by Ambassador Alexander Vershbow, who served as the US envoy to South Korea, Russia and NATO and is the former deputy secretary-general of NATO. He told me: “Even if the Democrats retake the White House, it’s going to take a lot of time to rebuild the habits of American leadership and to rebuild the confidence and trust on the part of our traditional allies that has been forfeited with the coronavirus and the pulling out of the WHO.

“I think that the attitudes that have been reflected in this policy of abdication of leadership now have deep roots in some parts of the American body politic and it’s not going to be easy – even with a change of administration – to go back to the way things were,” said Vershbow.

The global competition for Covid-19 resources

The United States also finds itself alone in its approach to develop a lifesaving Covid-19 vaccine with an America-first policy. Just ahead of the WHA, more than 140 world leaders and experts signed an open letter pushing for a patent-free “people’s vaccine” that will be free and produced at scale.

The effort, dubbed “Operation Warp Speed,” could cost the US government hundreds of millions of dollars, according to a senior administration official. The official said it’s a financial risk if the doses are ineffective, but worth it.

However, even if the US-led effort succeeds, the collateral cost could not only be a stronger China but also a diminished international stature for the United States and a regrettable loss of goodwill from other countries and multilateral bodies during the next pandemic or global crisis.